Crafting Legacy with Broken Pieces: Lee Family Fragments at Winterthur

Cecelia Eure

Citation: Eure, Cecelia. “Crafting Legacy with Broken Pieces: Lee Family Fragments at Winterthur.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, May 26, 2023.

Abstract: Hidden away at Winterthur is an archeological fragment collection donated by Mrs. Cazenove G. Lee in 1968 and 1969. The collection includes approximately 139 objects, primarily excavated, a term used loosely in this context), in early twentieth-century Virginia at Lee family homes. They are cataloged under collection numbers 1968.0312-0336 and 1969.0048-56, but this paper focuses on three objects: a stone, a pair of shingles, and a brick. As pieces collected following the destruction of the Civil War in a collection that largely ignores the southern United States, these fragments serve Winterthur as a means of preserving the destruction of the South, in contrast with the decorative arts that make up most of the museum’s collection. Additionally, many of these bricks, stones, ceramics, and glass pieces were likely crafted by enslaved Black workers, an ever-hidden legacy in the museum's collection. Eure starts by addressing the collection itself and the mythos around the Lee family and the fragment’s history. Then, she addresses the popularization of taking objects from the South in the economically unstable post-Civil War years. These fragments differ from the “pillaging the south” narrative for two reasons: First, the fragments were donated by a member of the Lee family, and second, the archaeological fragments are much more mundane than the rest of the objects held by Winterthur and are not on view. The fragments were accepted as part of the collection specifically to be a part of the study collection, according to the acquisition files. As fragments of what we might traditionally see at Winterthur, collected from elite properties, this collection of objects is a unique look into the role of archaeological fragments in material culture studies and the politics of legacy building.

Keywords: archaeology, post-Civil War, collections, material culture studies, historiography

Tucked away in storage crates throughout the Winterthur Museum are over 130 brick, stone, and glass fragments collected from historic Lee family properties in Virginia and Maryland in the 1920s and 30s by Cazenove Gardener Lee, Jr.[1] These artifacts stand in opposition to the rest of Winterthur. Henry Francis du Pont’s vision for Winterthur was to create period rooms, wherein objects sat as they would if they were not in a museum, but a home of its time.[2] Objects were not supposed to sit in boxes; yet, with over 90,000 collection objects, not everything can be on display. Why does Winterthur have so many Virginian fragments? As fragments of what we might traditionally see at Winterthur, collected from elite properties, this collection of objects is a unique look into the post-Civil War politics at play in Winterthur’s collections. They beg us to consider the opposing forces of southern and northern historic preservation efforts. The collection preserves two things Winterthur has yet to reckon with: the image of a destroyed post-war South and the Lee family legacy.[3]

This project focuses on three specific fragments in the collection, all from Virginia and labeled with their specific place of origin. A significant number of the collected fragments are foodservice ceramics and glass that are largely not labelled and are useful when considering the pieces that Virginians used in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries; however, they are separate from the scope of this paper. The tags on the fragments in question range from descriptive to incredibly vague, and C. G. Lee clearly did not have a specific cataloging system for his collection. The three selected objects are a stone (1968.0317), a tile fragment (1968.0324), and a brick (1969.0051).[4]

Winterthur’s collections have never emphasized the American South. Winterthur houses Virginian objects that range from an easy chair owned by George Washington’s sister, Betty, to a small collection of ceramics made in the Shenandoah Valley. There are 319 matching works under the search for Virginia as the primary creation place in Emu, Winterthur’s internal collections database. For comparison, the same search for objects created in Connecticut provides 4,786 results. A large portion of those 319 Virginian objects are archaeological materials.[5] Thus, to view one of the bricks in the fragment collection I traversed up to the ninth floor, past Yuletide decorations, down a dark hallway to a closet where I found a crate of bricks on the ground. Outside of architectural features and George Washington memorabilia, objects of the southern United States are the dusty skeletons in Winterthur’s closet.

Lee Legacy

Winterthur is not the only collector in this story. The first collector of these objects was the Lee family of Virginia, one of the so-called First Families of Virginia.[6] The title of First Family of Virginia is one that ignores the indigenous people that lived in the land that became Virginia for centuries prior to English settlement at Jamestown and the efforts of the Black enslaved laborers that allowed for these families to accrue substantial wealth in the region. This southern genteel identity is rooted in the erasure of some American stories and the preservation of a select few.

C. G. Lee was a founder of the Society of Lees in Virginia and writer and editor of its magazine, Magazine of the Society of the Lees of Virginia after retiring from a career as an engineer for the DuPont company.[7] His book, Lee Chronicle: Studies of the Early Generations of the Lees of Virginia, is made up of articles he wrote for the magazine between 1922 and 1939.[8] Not only was he a DuPont employee, but his mother was E. I. du Pont’s great-granddaughter, and his father was a (relatively distant) cousin to her. The Lee and du Pont families are intrinsically tied. Lee’s widow, Dorothy Vandegrift Lee, like her late husband, was passionate about historical preservation and donated the archeological collection to Winterthur in 1968 and 1969.[9] The fragment collection exists because of its association with this prominent family and their desire to preserve their own legacy as a part of the Lost Cause myth of the Old South.

The Society of the Lees in Virginia’s membership is made up of anyone who descends from Richard Lee, who was the first member of the family in what would become the United States and settled in Jamestown in either 1639 or 1640. Colonel Richard Lee, “the Emigrant,” established the Lees as one of the First Families of Virginia. He was a statesman, planter, merchant, and enslaver.[10] Richard Lee is an important character, as his early success in colonial Virginia provided the family with legitimacy in early American history. Wealth and prominence came quickly for the Lee’s and continues centuries after Richard Lee’s death. Presently, the most well-known family member is the infamous Confederate General Robert E. Lee, directly tying the family to the Confederate attempt to preserve the institution of slavery in the United States, despite efforts to disconnect the Confederacy from slavery.

When the Society of Lees of Virginia was founded in 1921, they described their ambitions as follows:

To draw the scattered members of the family together and through meetings, social gatherings, pilgrimages, and commemorative exercises to further a deeper feeling of fellowship among them; to assist in the preservation of those ancient burial places now lying neglected and forgotten; to aid in the compilation of data of family, state and national interest; to promote a greater knowledge of our ancestors’ services to their country, and to make better Americans of ourselves and our children.[11]

The still operating organization is upfront about their goal: to solidify their family name in American history and frame that task as a noble undertaking. The Lees of Virginia have always taken pride in their family identity, for better or worse, and their organization’s mission reflects a desire for society at large to hold the same reverence towards the family. Though the Lee family fought on the Confederate side of the Civil War, the family generally emphasizes that Robert E. Lee, “… opposed secession, deplored the presence of slavery, and cherished the Union.”[12] Notably, the family continues to highlight their former slave plantations. This narrative, regardless of its relationship with the truth, was important to the family’s continued effort to situate Robert E. Lee and their family at large among the American founding fathers and patriots. Following the end of the Civil War and Reconstruction, racial tensions were high in the South and increasing even more with the revival of the Ku Klux Klan following the release of the 1915 film, Birth of a Nation.[13] C. G. Lee and the Society went on pilgrimages to Lee family sites, and he wrote guides to these journeys. Lee likely collected the fragments at Winterthur over the years on these trips.[14] Though I refer to the fragments as archaeological, that term is used loosely, as these objects were likely just picked up as C. G. Lee explored. The United States was at a critical point for developing a national narrative at the early twentieth century. It was the height of Americana collecting, historic site preservation, and the Colonial Revival. The objects and accompanying notes in the collection illustrate the collecting philosophy of C. G. Lee and his intentions to craft his familial legacy for the next generation.

Figure 1: Small stone fragment labelled to be from Stratford Mill, October 11, 1931. 1968.0317.

Stone. Winterthur Museum. Gift of Mrs. Cazenove G. Lee.

The Stone, the Shingles, and the Brick

While it may just look like a rock, this small stone fragment, housed in the Winterthur metals study collection, has a small note tied to it, presumably placed by C. G. Lee, stating, “Sample of stone from Stratford Mill. Oct. 11, 1931.” Stratford Mill is a grist mill on the site of Stratford Hall, the most famous Lee family home and birthplace of Robert E. Lee, which has been reconstructed for historical interpretation. Robert E. Lee Memorial Foundation was organized in January 1929 “to acquire […] Stratford Hall […] and to restore, furnish, preserve, and maintain it as a natural shrine in perpetual memory of Robert E. Lee.”[15] As it was lost to the family after the Civil War, the estate was purchased for $240,000 during the Great Depression, and the previous owner vacated by July 1932.[16] The site was finally dedicated in 1935.[17] C. G. Lee collected this sample at the estate’s mill prior to the site’s purchase and restoration, presumably with the permission of the previous owner. The grist mill restoration occurred in 1939, when a new structure was built on the foundation of the old, right by the Potomac River.[18] This piece was meant to be a sample remanent of the gristmill structure that once was—a prize from the 1931 visit.

Figure 2 : Two roofing tiles tied together with a string and labelled to be from Shirley Plantation. 1968.0324.001 and .002. Ceramic. Winterthur Museum. Gift of Mrs. Cazenove G. Lee

The second object of interest is a pair of shingles from Shirley Plantation in Charles City, Virginia. Today, the plantation is a private residence with tours of the grounds available.[19] The string of Lee’s label is tied through the nail holes in the clay shingles, attaching them together. The tag reads, “Tiles from ‘Shirley’ said by Mrs. M. C. Oliver to have been original roofing.” Mrs. M. C. Oliver likely refers to Marion Oliver Carter, who lived at and helped manage Shirley Plantation during the 1920s and 30s and journaled about the plantation’s visitors beginning in 1927.[20] Though the Carter-Hill family presently and historically occupies Shirley, they are also relatives of the Lee’s. C. G. Lee’s collecting went beyond Stratford to show as far reaching a family influence as possible. It is possible that C. G. Lee visited Shirley and was given the shingles due to his interest in collecting similar objects.[21] The indication that he was given these tiles also highlights that “archaeological” is a term used loosely in this context; proper excavation techniques were likely not a part of this pick-and-choose process.

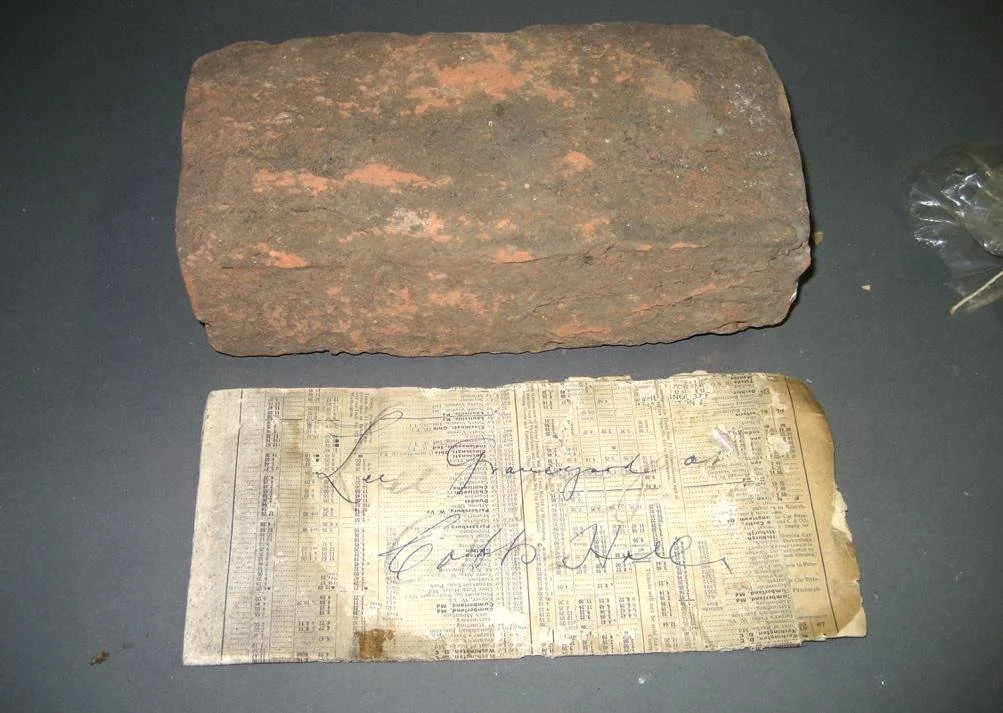

Figure 3: Brick from Lee Family graveyard at Cobbs Hall and note. 1969.0051. Earthenware. Winterthur Museum. Gift of Mrs. Cazenove G. Lee.

Bricks are one of the most common archaeological remnants, and when they are left in place, they can be highly informative.[22] This brick was found as a part of a brick wall surrounding a small section of the Lee family graveyard at Cobbs Hall. walled off section contained the previously undiscovered grave of Richard Lee. In his writings C. G. Lee described the brick wall to have been, “a collection of very old and crude brick.”[23] The preserved brick is accompanied by two notes, one is written on a Baltimore & Ohio Railroad timetable and says, “Lee graveyard at Cobb Hall” and the other tied on to a plastic storage bag stating, on two sides, “Lee graveyard at Cobbs Hall / written on a B&O timetable / CGL Jr. Collection / in Northumberland County / Consult Lee Chronicle index p. 380.”[24] Since Lee Chronicle was published in 1957, twelve years following Lee’s death, he did not write the section note. It is likely that his wife or someone at Winterthur wrote the tag. The referenced pages of Lee Chronicle outline the discovery of the graveyard and Richard Lee’s burial site in 1927. Additionally, it includes a map of the site at Cobbs Hall. The family’s preservation efforts at this time were partially focused on the upkeep of graveyards. This brick is a memento of the grave site without disturbing the graves themselves. According to collections records, this brick has never been taken out of storage for formal study.[25]

Collecting the South at Winterthur and Beyond

Following the Civil War, economic hardship in the South made for a great opportunity for northern collectors to acquire goods of the “Old South” for a reasonable price. Black and white southerners sold antiques out of financial necessity to northern dealers who coveted the romantic image of plantation days gone by. For example, the Montmorenci staircase at Winterthur was purchased from a house in North Carolina because of this trend and its stylish beauty in the 1930s.[26] By the 1920s, when C. G. Lee initiated much of his collecting, this romantic image was less desirable and northern antiques dealers began selling southern objects under false northern identities when they could. Southern antique sales only increased at this time, especially objects sold by Black southerners.[27] The Winterthur Museum reflects the bias toward northern object identity, as many objects are automatically assumed to be from Pennsylvania, and fine antiques are rarely initially attributed to the South. Should the provenance of each object in the collection be thoroughly studied again, it is plausible that more southern objects are present than are officially recorded. For now, we have these fragments, pieces of the false grandeur of the Old South proudly brought to Winterthur for the sake of the Lee name. These objects are so close yet so far to those “pillaged” from the south at the turn of the twentieth century.

The question remains, why are these objects housed at Winterthur? Mrs. C. G. Lee did not solely donate the fragment collection. She also donated a fair amount of fully intact objects to the museum, including some Chinese export porcelain, a portrait of Mary Bland, wife of Henry Lee of Cobbs Hall, and a collection of photographs of portraiture and Lee family homes.[28] The fragments were noted in a 1968 memo to be, “fine additions to the study collection” and the photographs were described as, “welcome additions to our material relating to Southern families.”[29] The focus on Southern families is important here, as it certainly does not signal a desire to study the South and its people at large, rather to study the grandeur of Old Southern families like the Lees.[30] Perhaps there was a moment wherein Winterthur desired to emphasize southern history, or perhaps the fragment collection was accepted so that Mrs. Lee would continue to donate other objects from her collection to the museum. Most museums have more in their archaeological collections than they know what to do with and studying fragment collections that were perhaps haphazardly collected can be particularly difficult. Though Winterthur does not have a particularly large archaeological collection, the presence of archaeological fragments feels out of place in the museum’s decorative arts focused holdings.[31]

Future

All these objects were likely crafted and handled by enslaved laborers. In 1742 there were approximately 200 people enslaved by the Lee family at Stratford and the other smaller properties owned by Thomas Lee alone.[32] The tags that accompany the objects are the only records of provenance, and they focus entirely on the white family associated with their ownership. Even though the fragments largely highlight the buildings that housed the Lee family, these objects are far more representative of the everyday craftsmanship of Black Americans. Should Winterthur or any other institution choose to interpret this collection in the future, Black labor and narrative creation in the South should be at the center.

It is my opinion that the C. G. Lee fragment collection would better suit the collections of a site like Stratford Hall or the archives at Washington and Lee University. Not only does Stratford host their own archaeological collection, but their focus is on the Lee family legacy.[33] While Winterthur and the du Pont’s do have a familial connection to the Lees and the collection, it simply falls outside of the Winterthur collecting scope. Since the objects were selected seemingly at random, they tell us very little about architecture and life in the south. Frankly, they compare more so to souvenirs of travel and time than useful artifacts for scholarship-- the wealthy Southern family version of owning a piece of the Berlin Wall. By hosting these objects Winterthur simultaneously perpetuates the image of the South as a destroyed place and legitimizes the legacy building undergone by the Lee family in the early twentieth century.

Conclusion

From both the Lee and the much more subtle Winterthur perspective, the fragment collection is intended to summon a specific recollection. These fragments ask their viewer to remember that the Lee family was powerful in the antebellum period and should be highly regarded in American memory. Winterthur’s connection with these objects is much more complicated. The stone, the tiles, and the brick were never meant to be seen by the public, as they are a part of the study collection. They hide in boxes and closets waiting for researchers to take an interest in them. As broken objects, they allow for the perpetuation of the image of the South as broken; as objects from the Lee family, they problematically highlight the family’s legacy. While most of Winterthur’s collection can be studied and valued based on its style, craftsmanship, and function, the fragment collection’s value in the museum setting entirely stems from the family that used to own it. There are certainly other objects in the collection that are valued for their connections, like Paul Revere’s silver tankards, but their connections work in tandem with their monetary value. To engage with these fragments is to engage with a legacy of rewriting history and preserving the Lost Cause, something I hope to see northern museums housing southern objects grapple with in the future.

Endnotes

[1] This project came about following a search in Winterthur’s internal museum collections database, Emu, for the location “Virginia.” H.F. du Pont notoriously did not collect many objects from beyond 1840 or south of Maryland.

[2] John A.H. Sweeney, “Henry Francis DuPont: Observations on the Occasion of the 100th Anniversary of His Birth May 27, 1980,” The Henry Francis DuPont Winterthur Museum, 1980.

[3] This paper was initially conceived as a part of Material Life in America, a seminar taught by Dr. Martin Brückner, at the University of Delaware/Winterthur. The feedback from my colleagues was instrumental to my research.

[4] This project came about following a search in Winterthur’s internal museum collections database, Emu, for the location “Virginia.” H.F. du Pont notoriously did not collect many objects from beyond 1840 or south of Maryland.

[5] Most of the glass and earthenware fragments in this collection are not attributed to Virginia, so they are not included in the 319 Virginian objects. Rather, these are broadly credited to England or the United States. An example of this is object 1968.0333.003.

[6] The First Families of Virginia were a group of wealthy elites in colonial Virginia, including families like the Lees and the Washingtons.

[7] DuPont refers to the company; du Pont is the surname.

[8] Cazenove Gardner Lee, Lee Chronicle: Studies of the Early Generations of the Lees of Virginia, ed. Dorothy Mills Parker (New York: New York University Press, 1957).

[9] Jay Roberts, “Cazenove-Lee-DuPont Story” (Alexandria, VA, May 15, 2018), https://jay.typepad.com/william_jay/2018/05/cazenove-lee-dupont-story.html.

[10] Paul C. Nagel, The Lees of Virginia: Seven Generations of an American Family (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 8–15, http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0723/90007195-b.html.

[11] Lee, Lee Chronicle.

[12] Nagel, The Lees of Virginia, 266.

[13] David Pietrusza, “The Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s,” Bill of Rights Institute, accessed December 16, 2022, https://live-bri-dos.pantheonsite.io/essays/the-ku-klux-klan-in-the-1920s/.

[14] Lee, Lee Chronicle, 313.

[15] Lee, 101.

[16] Lee, 102.

[17] “Our History,” Stratford Hall, accessed December 16, 2022, https://www.stratfordhall.org/history/.

[18] “Grist Mill,” Stratford Hall, accessed December 16, 2022, https://www.stratfordhall.org/grist-mill/.

[19] “Shirley Plantation,” accessed December 16, 2022, https://www.virginia.org/listing/shirley-plantation/4174/.

[20] Penelope Cottrell-Crawford, History of a Landscape: Shirley Plantation (The Garden Club of Virginia, 2019), 32, https://issuu.com/cottrellcrawford/docs/shirley_plantation_landscape_history.

[21] Paul C. Nagel, The Lees of Virginia: Seven Generations of an American Family (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0723/90007195-b.html.

[22] Ivor Noël Hume, A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America, [1st ed.] (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970), 80.

[23] Cazenove Gardner Lee, Lee Chronicle: Studies of the Early Generations of the Lees of Virginia, ed. Dorothy Mills Parker (New York: New York University Press, 1957), 40.

[24] The always helpful WPAMC Class of 2024 helped figure out what B&O means and decipher some of the handwriting on this tag.

[25] The other two objects featured in this essay have each been moved for study at least once.

[26] “Montmorenci Stair Hall,” Winterthur Mobile Guide, accessed December 16, 2022, https://www.oncell.com/sr/CWsDb/?lang=en. Brought to my attention by Laini Farrare.

[27] Trent Rhodes, “The Antiques Trade in Transition: Collecting and Dealing Decorative Arts of the Old South” (University of Delaware, 2018), 8–10, http://udspace.udel.edu/handle/19716/23777.

[28] The Cazenove-Lee Family Papers are housed in the Winterthur Library’s Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera under call number 83.

[29] Charles Hummel, “Executive Committee Agenda,” memorandum, October 31, 1968, Winterthur Archives.

[30] Let’s not forget, the prominently featured George Washington was a Virginian, not that his association with the state helped with its representation at Winterthur.

[31] Barbara L. Voss, “Curation as Research. A Case Study in Orphaned and Underreported Archaeological Collections,” Archaeological Dialogues 19, no. 2 (December 2012): 145–69, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203812000219.

[32] “Enslaved Community,” Stratford Hall (blog), accessed December 16, 2022, https://www.stratfordhall.org/enslaved-community/.

[33] “DuPont Library & Collections,” Stratford Hall (blog), accessed December 16, 2022, https://www.stratfordhall.org/dupontlibrary/.

Bibliography

Cottrell-Crawford, Penelope. History of a Landscape: Shirley Plantation. The Garden Club of Virginia, 2019. https://issuu.com/cottrellcrawford/docs/shirley_plantation_landscape_history.

Hummel, Charles. Memorandum. “Executive Committee Agenda.” Memorandum, October 31, 1968. Winterthur Archives.

Lee, Cazenove Gardner. Lee Chronicle: Studies of the Early Generations of the Lees of Virginia. Edited by Dorothy Mills Parker. New York: New York University Press, 1957.

Nagel, Paul C. The Lees of Virginia: Seven Generations of an American Family. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0723/90007195-b.html.

Noël Hume, Ivor. A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. [1st ed.]. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970.

Pietrusza, David. “The Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s.” Bill of Rights Institute. Accessed December 16, 2022. https://live-bri-dos.pantheonsite.io/essays/the-ku-klux-klan-in-the-1920s/.

Rhodes, Trent. “The Antiques Trade in Transition: Collecting and Dealing Decorative Arts of the Old South.” University of Delaware, 2018. http://udspace.udel.edu/handle/19716/23777.

Roberts, Jay. “Cazenove-Lee-DuPont Story.” Alexandria, VA, May 15, 2018. https://jay.typepad.com/william_jay/2018/05/cazenove-lee-dupont-story.html.

“Shirley Plantation.” Accessed December 16, 2022. https://www.virginia.org/listing/shirley-plantation/4174/.

Stratford Hall. “DuPont Library & Collections.” Accessed December 16, 2022. https://www.stratfordhall.org/dupontlibrary/.

Stratford Hall. “Enslaved Community.” Accessed December 16, 2022. https://www.stratfordhall.org/enslaved-community/.

Stratford Hall. “Grist Mill.” Accessed December 16, 2022. https://www.stratfordhall.org/grist-mill/.

Stratford Hall. “Our History.” Accessed December 16, 2022. https://www.stratfordhall.org/history/.

Sweeney, John A.H. “Henry Francis DuPont: Observations on the Occasion of the 100th Anniversary of His Birth May 27, 1980.” The Henry Francis DuPont Winterthur Museum, 1980.

Voss, Barbara L. “Curation as Research. A Case Study in Orphaned and Underreported Archaeological Collections.” Archaeological Dialogues 19, no. 2 (December 2012): 145–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203812000219.

Winterthur Mobile Guide. “Montmorenci Stair Hall.” Accessed December 16, 2022. https://www.oncell.com/sr/CWsDb/?lang=en.