In the Absence of Body Hair:

Riza Abbasi’s Nude and its Analysis as the Ideal Persian Woman

Delfin Öğütoğullari

Citation: Öğütogulları, Delfin. “In the Absence of Body Hair: Riza Abbasi’s Nude and Its Analysis as the Ideal Persian Woman.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, February 26, 2021.

CW: This article features discussion of past sexual practices that included the involvement of children, which may make some readers uncomfortable, anxious, or angry. Please continue at your own discretion.

Abstract: This paper focuses on a painting by the Safavid artist Riza-i Abbasi called “Reclining Nude” (ca. 1590) from Isfahan, Iran. The image portrays a naked female figure dressed in diaphanous cloth resting near a small stream. She holds a letter in her hand and appears to be daydreaming or contemplating with her eyes closed. Such printed images circulated in Safavid Iran through European merchants and Christian missionaries who were invited to the court of Shah Abbas I (r: 1588-1629). Scholars have considered this image to be based on a Renaissance engraving of Cleopatra by Marcantonio Raimondi.The suggestion that the recumbent nude of Riza Abbasi was worked from the Cleopatra engraving of the Italian Renaissance printmaker Marcantonio Raimondi (ca. 1480-1534) plays into the notion that a Persian woman was assumed to be European solely due to her naked form. Even the name “Reclining Nude” inherently imposes the concept of the farangi and further removes the subject from her Persian attributes; however, the depiction of Riza Abbasi’s nude female follows the traditional concept of ideal women in Persian literature. In this paper, I will further analyze the imposed European identity on Riza Abbasi’s nude. Through this examination, I will argue that the theme of a female nude with long dark hair without body hair has its roots in the love portrayal of the beloved from Persian poetry and paintings rather than a European prototype. Furthermore, I will examine Reclining Nude’s Persian origins with the implications of her body hair, or lack thereof, derived from depictions of the archetypal pubescent beloved in Persian literature.

Key words: Reclining Nude, Safavid art, Riza-i Abassi, Persian literature, farangi, beloved

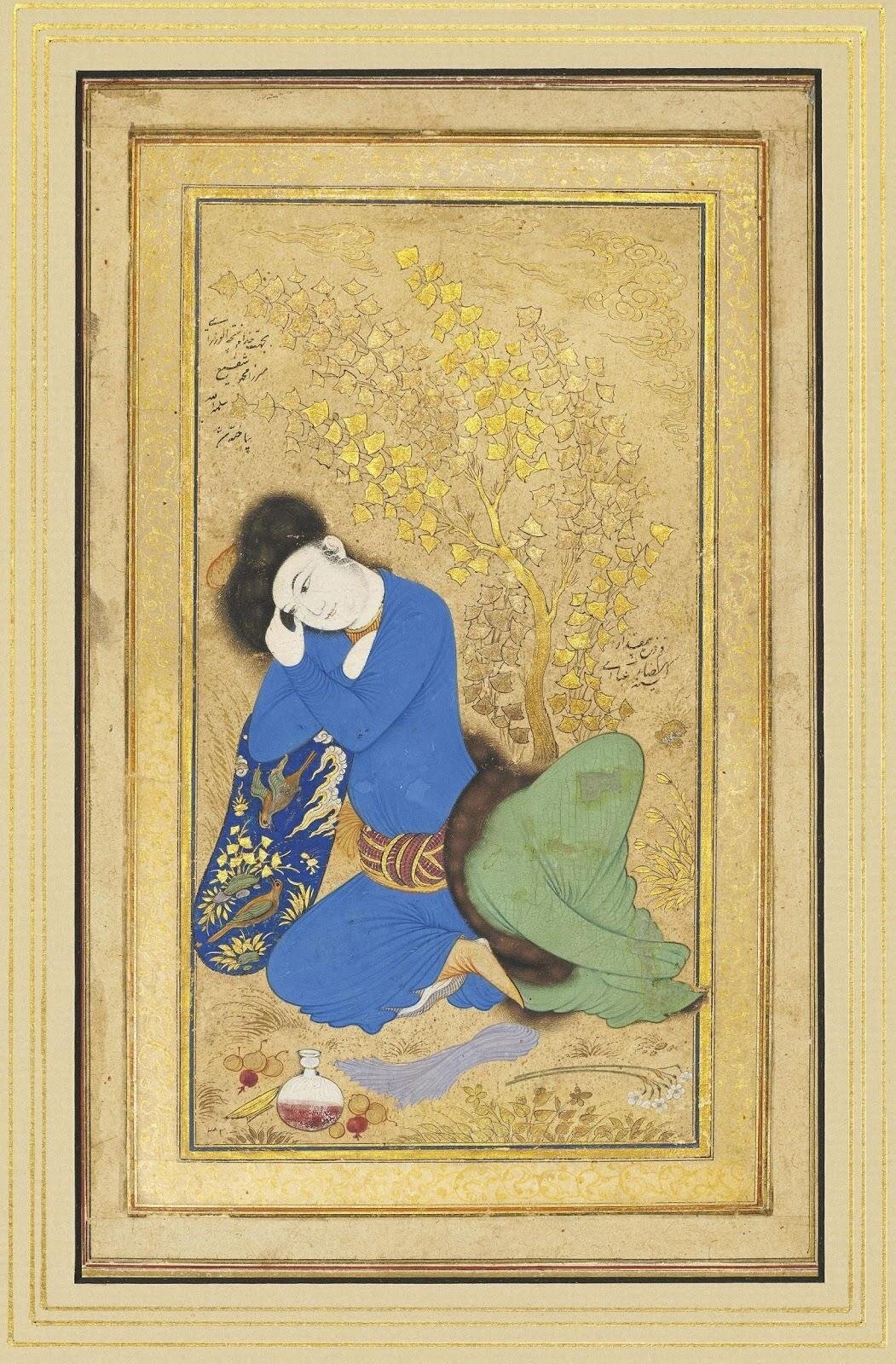

(fig.1) “Reclining Nude” Signed by Riza Abbasi (ca.1565-1635) Safavid period, Reign of Shah Abbas, Iran ca. 1590 illustration: 9 x 16 cm (3 5/8 × 6 9/16 in) National Museum of Asian Art, Freer & Sackler Collection, Washington D.C.

In the album page Reclining Nude by Riza Abbasi, a naked female is shown enveloped in sheer drapery and resting near a stream (fig. 1). Riza used silver to illuminate the movement of water- which appears dark and ashy due to oxidation. Riza gives the woman’s body a sense of airiness, highlighted by the unraveling ends of her transparent shawl. Her torso rests on her clothing while her shoes are placed right next to her feet- the blue inner lining complementing the blue hues of nature. Due to the format of the single-page composition, the illustrated scene of Reclining Nude at 9x16cm (3 5/8 × 6 9/16 in) is separate from that of the illumination and calligraphy that dominates the page, leaving no choice but to approach the illustrated scene. This small scale invites the viewer to look closely at the subject’s nudity.

Reclining Nude adheres to Persian visual culture by using stylistic elements such as the Persian moon-face type, which includes almond-shaped eyes, a heart-shaped mouth, arched eyebrows, and curled locks of hair in front of her ears. Her lips are pursed together, hinting at a smile spawned from a daydream, perhaps of a lover. The woman’s eyes are closed- unaware of the gazes on her naked body. Her formulaic moon-face creates an anonymity about her identity, while her bare nudity adds tension and discomfort to the composition. Scholars such as Sheila Canby and Amy Landau argue that Riza could have studied a European engraving for the Reclining Nude image.[1] However, the direct idealization of her moon-face, her overtly sensualized body, the letter in her hand, and the garden setting, along with the absence of body hair, show that Riza Abbasi was instead looking at depictions of ideal Persian beauty such as the beloved.

In this paper, I will further examine the notion of the European image that was imposed on Riza Abbasi’s nude. Through this examination, I will argue that the theme of a female nude with long dark hair set near a small brook has its roots in the love portrayal of the beloved from Persian poetry and paintings rather than a European prototype. [2] Furthermore, I will analyze Reclining Nude ’s Persian origins with the implications of her body hair, or lack thereof, derived from depictions of the archetypal pubescent beloved in Persian literature.

Removing Reclining Nude from a Euro-Centric Analysis

(fig.2) “Cleopatra lying partly naked on a bed” Marcantonio Raimondi ca. 1515-1527, Engraving, 11.5 x 17.6 cm, Bologna, Italy, Metropolitan Art Museum, New York City

Sheila Canby argues that, due to the rarity of nude themes in the late 16th-century Iranian paintings, a European prototype of the Italian Renaissance printmaker Marcantonio Raimondi’s Cleopatra engraving (ca. 1480-1534) could have been used for Reclining Nude. [3](Fig.2) During the late 16th-century, following the global expansion of trade, European missionaries and tradesmen became recurring figures in Safavid ports- encouraging the exchange of material culture. Soon, their presence was linked to the representation of sexual mores-- creating debates around women’s decorum, same-sex practices, and prostitution.[4] However, the eroticization of the female form and male-male sexual practices in Persian paintings and literature developed before and outside of occidental notions.

Reclining Nude’s assigned European identity by academia is solely based on her vivid nakedness and her reclining pose. Due to this constant growing contact between Europe and Iran, instead of analyzing Reclining Nude’s origins of Persian courtly love, scholars have focused on the blunt eroticization of her body, which led to her characterization as the farangi. [5] Farangi can be translated as a “European” person in Safavid, Iran. However, the Reclining Nude is unmistakably depicting a Persian woman, using moon-face type in a distinctly Persian garden setting. The examination of Reclining Nude as farangi illustrates that a Persian woman was assumed to be European solely due to her naked form. Even its title “Reclining Nude,” popularly used for European nude studies, inherently imposes the concept of the farangi and further removes the subject from her Persian attributes

Compositionally, Riza clearly was not following the Cleopatra engraving as Canby suggested. Cleopatra is depicted with snakes on her upper arms, perhaps referring to the moments after she was bitten. The highly circulated Greek texts, like Cleopatra’s story, were common in Islamic visual and literary culture.[6] As these texts were adopted into Persian literature, Riza was certainly aware of Cleopatra and her attributes. Knowing the theme of this engraving, Riza would have added the snake details on the Reclining Nude ’s arm, if he was following the prototype. The Cleopatra engraving shows the subject indoors and positioned on a cushion, while its Persian counterpart rests on the ground atop her clothing. Furthermore, Reclining Nude ’s nudity was the reason for her appointed European identity. However, when compared, the imposed European prototype is not even shown fully naked.

In addition to the figural differences with Cleopatra, the garden setting of the Reclining Nude’s composition removes her from the notion of the farangi. The setting of gardens in Persian literature refers to the paradise of love, and particularly to its fantasy and mysticism which evokes courtly desires.[7] For instance, in Nizami’s highly circulated book of poems, Khamsa, he uses the verdant garden setting for the lover’s first interaction with each other. In Reclining Nude, the river she lays next to is intentionally bounded by rocks with flowers bursting through them while her bare body is only covered with a see-through shawl-- which evokes voyeuristic love of the male gaze. The juxtaposition of the fruitful garden setting against the stark nakedness of the subject is further emphasized by the portrayal of the subject alone in the composition.

(fig.3) Detail of the letter, “Reclining Nude” Signed by Riza Abbasi (ca.1565-1635), Safavid period, Reign of Shah Abbas, Iran. ca. 1590, illustration: 9 x 16 cm (3 5/8 × 6 9/16 in), National Museum of Asian Art, D.C.

Although Reclining Nude stands alone in the fruitful garden, the presence of another person, a lover, is suggested by Riza Abbasi. The lover’s company and gazing eyes are prevalent through the placement of a letter in the hand of Reclining Nude (fig.3). The letter reads: “The man’s eyes, perhaps he saw himself in a dream.”[8] Scholar Esin Atil argues that the letter is an implication that the nude figure is the dream of Riza Abbasi. However, the letter suggests the existence of a story outside the bounds of the image, and intentionally imposes a man’s eyes on her naked form--implying the gaze of a voyeuristic lover. The lover is not only present in the letter, but also possibly in her dream. The gazes on her naked body are not only limited to that of the lovers, but also the audience-- who are struck by her direct nudity. The overtly sensualized figures of the single-page format, like Reclining Nude, do not correspond to a single figure from Persian literature. On the contrary, these ambiguous characters are a fusion of several ideal beauties from literary tradition. Furthermore, it is important to note that these sensualized portrayals of the female form date back to depictions of Shirin in Nizami’s Khamsa, and to the representation of Eve in religious and historical Persian manuscripts.[9] To illustrate, the folio of The owner of the garden discovers maidens bathing in his pool, from the Timurid period, shows eight half-naked maidens bathing in a pool while the owner of the estate tries to glimpse their bare chests (see Image at British Library). This folio is not only an example of the eroticization of women prior to encounters with the Western World, but also shows the commonality of the voyeuristic lover theme in Persian culture. Hence, academia’s categorization of Reclining Nude as a farangi based solely on her nudity can be discounted, as this kind of nudity was already prevalent in Persian visual tradition.

Reclining Nude as the Beloved

Although the Reclining Nude is strikingly naked, her locks of dark hair fall over her naked voluptuous body. The dark curls of the beloved’s hair serve as an instrument by which to facilitate her interactions with the voyeuristic lover-- helping her disguise and reveal her beauty selectively. The beloved in Persian poetry is often a passive loved person who is subjected to the desires and passions of a voyeuristic lover. The locks of the beloved often play a captivating role in Persian literature/visual culture, where the lover is lost in the details of the dark curls. Reclining Nude is shown completely naked because her lover is figurally absent from the composition thus giving her privacy. In her solitude she is unaware that she is being watched. Hence, she does not disguise her naked form with her hair. In lyrical poems, intense emphasis is placed on the hair around the forehead and sides of the beloved’s face, like the framing of Reclining Nude ’s plump cheeks. The intricacy of her curls helps the viewer to identify her as a beloved.

Often regarded as courtly romance or courtly love, the relationship between the beloved and the lover is inhibited with sensual desire. The tension between the lovers is often depicted through eroticization and daring depictions of adultery. However, the beloved is usually a fourteen-year-old boy who is subjected to the sexual desires of grown men. Yet, the attributes and the personality of the beloved are interchangeably applied to any figures of erotic desire. In the Reclining Nude image, the artists chose to compositionally and figurally depict the beloved in a nude female form laying in a garden.

Riza Abbasi had the independence to freely interpret the beloved as an adult female due to the single-page format. Artists started to receive different single-page commissions from various classes when the royal patronage of Shah Tahmasp neglected the court artists.[10] In royal book commissions, the illustrated scene is often accompanied by a written text that explains the story behind the visual narrative. In single-page format, with the elimination of the accompanying texts, the artists have the independence to show individual eroticized figures without the background story of their nakedness. Thus, Riza’s interpretation of a beloved was not bound to the limits of a written story.

Her bare body is even further emphasized by the juxtaposition between her thick head hair and the total absence of body hair. The portrayal of a woman without any body hair stems from the archetype of the hairless prepubescent beloved; however, the pubescent form in Persian culture was seen as indeterminate of a person’s gender.11 Sodomy, which is prohibited by the Islamic Law, did not apply to grown men’s relationship with young boys. In fact, a mature man’s sexual relations with pubescent boys was seen as the equivalent of having sex with a genderless person. According to scholar Khaled el-Rouayheb, the term “homosexaulity” from the binary contemporary Western terminology, when imposed on the beloved’s relationship, brought certain semantic limitations. The culture under discussion did not share western concepts of homosexuality. According to J. T. Monroe, Islamic jurisprudence understood homosexual attractions as innate.[12] Contrary to Christianity, which regards homosexuality as a pathological character defect, Islamic scholars argued that a man gazing at and enjoying the beauty of a handsome beardless boy should not lie about their lust. [13] Like the classical Greek and Roman cultures, they evaluated a beloved’s role depending on their active or passive sexual role, and not according to their gender. Therefore, the representation of courtly love with boys and expressing this love in verse was not considered an illicit act. The love portrayal of boys and their attributes were easily employed on grown women’s depictions due to this genderless notion of the adolescent body.

In Reclining Nude, when depicting this ideal beauty of the beloved as a woman, due to the genderless notion of the adolescent beloved, Riza chose to impose the attributes of pubescent form onto a fully developed female. The imposition of a hairless body on grown women was easily adapted due to unacceptability of body hair in Islam. The hadith by Abu Hurayrah that put forth the requirement of removal of pubic and underarm hair, as it was seen as impure or unnatural.[14] In order to keep up with hair standards, Safavid women plucked out their eyebrows to echo the shape of a crescent and used wax or razors to shave and completely remove their pubic, armpit, and leg hair. Additionally, the Shi’ite belief argues that on the day of the apocalypse, a bearded woman will announce the coming of the Twelfth Imam.[15] As a bearded woman is put in the commanding position of the apocalypse, the presence of body hair is further emphasized as a sign of evil in Iran.

Furthermore, the Reclining Nude follows the attributes of the young hairless boy because, as a female, she is also the penetrated beloved. The numerous paintings, pencil boxes, book illustrations, and Riza Abbasi’s own single-page portrayal of a youth with a bearded men, illustrate that the beloved mainly conformed to the age-constructed same-sex love.[16] In single-page visual culture, due to the absence of accompanying text and the formulaic nature of moon-face type, to differentiate between the penetrated moon-faced beauty and the grown bearded lover, the penetrated pubescent boy was often depicted without any body hair to emphasize his youthfulness.

(fig.4) Youth and Dervish, Riza Abbasi, Second quarter of the 17th-century, Isfahan, Iran. Ink, transparent and opaque watercolor and paper, 12.7 cm x 5.4 cm, accession number: 25.68.5. Metropolitan Art Museum, New York City

In Riza’s Youth and Dervish, a bearded and a beardless figure is shown drinking in a garden setting, similar to the verdant landscape of Reclining Nude. Riza has intentionally placed visual cues for the intended audience--the aristocracy--to identify the figure as a penetrated beloved (fig.4). The fur lining of the pubescent boy and his gesture of offering wine are hinting at his sexual role as these elements are commonly worn in single page representations of erotic courtly scenes. The intended audience of the time would have understood his gesture of handing a wine glass as an indication of the sexual tension in the composition. Furthermore, Riza has applied the striking burgundy on the shawl that wraps the waist of the beloved-- framing his pubic area. These visual cues are similar to the positioning of Reclining Nude’s vulva at the center of the composition. The penetrated beloved and Reclining Nude not only share the pubescent body hair standards, but also the classic Persian moon-shaped face. The standardized nature of the moon-face type allows its attributes to be used both for men and women, which further bends the gender binary.

The Lovers by Riza Abbasi further illuminates the gender blurring factor of the Persian moon-face type (fig.5). The scene shows two figures in a garden setting similar to the Reclining Nude. They are drinking and enjoying a courtly pastime. The Lovers are depicted with plump, pale faces and curvy, smooth contours, similar to the youthful round form of Riza’s Nude. Their facial features are strikingly similar, with their heart-shape mouth and arched eyebrows. Like the Reclining Nude’s stout smirky face, The Lovers’ soft smiling expressions are framed with locks of curled hair. It is hard to determine the gender of the figures as both are depicted in lavish clothing that covers their genitalia and both embody the same facial traits. Through the elimination of their individual features, the courtly lovers suggest both a homo-erotic and hetero-sexual scene.

(fig.5) “The Lovers,” Riza Abbasi, Dated 1630. Safavid Period, Isfahan, Iran, Opaque watercolor, ink and gold on paper, Illustration: 17.5 x 11.1 cm. Accession number: 50.164, Metropolitan Art Museum, New York City

(fig.6) A Seated Youth, signed Reza ‘Abbasi, Safavid Isfahan, Iran, circa 1630. Opaque pigments on paper. Painting 7 ½ x 4 in (18.9 x 10.2 cm); folio 10⅛ x 6 ¼ in (25.4 x 16 cm). Sold in 2018 at Christie’s in London

The reason for the direct nudity found in these folios is derived from the sexual desires of women in Persian literary texts. Women are often depicted as mischievous or even sexually charged. [17] This sexual lust of women is intensified in the composition with the direct portrayal of Reclining Nude’s genitalia.[18] Mounted as an album page, A Seated Youth by Riza Abbasi depicts a young beloved boy, depicted in moon-face type, in an outdoor setting while he is sitting and contemplating (fig.6 or see figure at Christie’s). The emphasis on the lack of facial hair is the indication of his adolescence. Unlike the Reclining Nude, A Seated Youth is depicted in lavishly drapery that complement the lapis blue baluster cushion. However, when the beloved is rendered as a female, her clothes are taken away to further sensualize her through the smooth contours of her curvy naked form.

Riza has portrayed Reclining Nude’s pubic area without body hair to conform to the standards of the homo-eroticized pubescent lover. In fact, the presence of body hair on women in Persian culture was connected to the personification of a demon (div) who is female with extensive body hair.[19] As the presence of hair showed a women’s place in the 16th-century Safavid Iran, the absence of hair also showed their class and ranking in society. The Reclining Nude’s understanding as a Persian woman not only allows further research to examine the folio’s connections to Persian literary culture but also eliminates the euro-centric analysis of nude images from Safavid, Iran. The Reclining Nude’s interpretation of the beloved allows the analysis gender blurring factor of archetypal moon face beauty and illuminates the free adaptation of the stories due to the single page format. Riza’s Reclining Nude did not aim to anatomically depict a female form but strived to put forth an imagery of a pubescent beloved inherently without any body hair.

Endnotes

1. Sheila R. Canby, The Rebellious Reformer: the Drawings and Paintings of Riza-Yi Abbasi of Isfahan (1996), 28-30.

2. Love portrayal is a term used to depict scenes in which courtly figures are showing physical and sensual touch, or gestures that are commonly understood as creating sexual tension, see Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh, and Canby, Sheila R. Persian Love Poetry, (2005).

3. Amy Landau, “Visibly Foreign, Visibly Female: The Eroticization of Zan-i Farangī in Seventeenth-Century Iranian Painting,” eds. Francesca Leoni and Mika Natif, in Eros and Sexuality in Islamic Art (2013), 99-129

4.Khaled El-Rouayheb,. Before Homosexuality in the Arab-Islamic World, 1500-1800, (2005).

5. Sheila Canby, “Farangi Saz : the Impact of Europe on Safavid Painting.” (1996)

6. El-Rouayheb, 2005.

7. Love poetry was one of the most studied themes in Persian poetry. Nizami extensively studied the mysticism of love through analogies of flowers, moon, and springtime. In his most revered stories, Leyla and Majnun, and Shirin and Khusraw, the element of voyeurism is used frequently, for translation of love poetry, see Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh, and Canby, Sheila R. Persian Love Poetry, (2005).

8. Esin Atil, “Reza Abbasi and his recumbent nude by water’s edge.” (2003) 78-79

9. Nimet Allam Hamdy, “The Development of Nude Female Drawings in Persian Islamic Painting.” (1979), 431-432.

10. Massumeh. “Safavid Single Page Painting, 1629-1666.” (1987), 92-112.

11. El-Rouayheb, 2005, 56-63.

12. Monroe, James, T., “ The Striptease That Was Blamed on Abu Bakr’s Naughty Son,” (1997),16-17.

13. El-Rouayheb 2005, 59.

14. Abu Hurayrah, who was seen as narrating the most hadiths, was criticized by Ali, Aisha, and Umar. Aisha is quoted to say how she wanted to correct the words of Abu Hurayrah regarding women, see Damanhuri. “Contextualization of Hadith. To Oppose the Patriarchy and Dehumanization in Building the Civilization of Gender in Islam.” (January 1, 2018): 143–156.

15. C. Bromberger, “Hair: From the West to the Middle East through the Mediterranean,” (2007), 379-399.

16. Leoni, Francesca, and Mika Natif. Eros and Sexuality in Islamic Art. (2013), 1-19.

17. Trickery of women in the Islamic culture was a prominent element in literary texts. In Kitab al-'Unwan ft Makayid al-Niswan, by the ninth/fifteenth-century Ibn al-Batanuni, women’s deceit is elaborately depicted, see Malti-Douglas, Fedwa. Woman’s Body, Woman’s Word : Gender and Discourse in Arabo-Islamic Writing. (1991), 54-66.

18. Analogy to women’s genitalia is present in Nizami’s work Haft paykar, see Niẓāmī, The Haft Paykar: a Medieval Persian Romance, trans. Julie Scott Meisami.

19. Omidsalar, M. (1995). “ DĪV”. Encyclopædia Iranica. VII/ 4, pp. 428-43; available online at: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/div. (accessed online on December 15th 2020).

Bibliography

Atil, Esin. “Reza Abbasi and his recumbent nude by water’s edge.” Art and Culture Magazine. (2003) 78-79.

Bromberger, C. (2008). Hair: From the West to the Middle East through the Mediterranean (The 2007 AFS Mediterranean Studies Section Address). The Journal of American Folklore, 121(482), 379-399.

Canby, Shelia. “Farangi Saz : the Impact of Europe on Safavid Painting.” Silk and Stone : The Art of Asia (1996).

Canby, Shelia R. The Rebellious Reformer: the Drawings and Paintings of Riza-Yi Abbasi of Isfahan (London: Azimuth Editions, 1996), 28-30.

Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh, and Canby, Sheila R. Persian Love Poetry London: British Museum Press, 2005.

Damanhuri. “Contextualization of Hadith. To Oppose the Patriarchy and Dehumanization in Building the Civilization of Gender in Islam.” Italian Sociological Review (January 1, 2018): 143–156.

El-Rouayheb, Khaled. Before Homosexuality in the Arab-Islamic World, 1500-1800 : Khaled El-Rouayheb. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Landau, Amy, “Visibly Foreign, Visibly Female: The Eroticization of Zan-i Farangī in Seventeenth-Century Iranian Painting,” eds. Francesca Leoni and Mika Natif, in Eros and Sexuality in Islamic Art (Ashgate Publications 2013), 99-129

Leoni, Francesca, and Mika Natif. Eros and Sexuality in Islamic Art Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013. 1-19

Malti-Douglas, Fedwa. Woman’s Body, Woman’s Word : Gender and Discourse in Arabo-Islamic Writing. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991, 54-66.

Massumeh. “Safavid Single Page Painting, 1629-1666”. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1987. 92-112

Monroe, James T. “ The Striptease That Was Blamed on Abu Bakr’s Naughty Son,” Homoeroticism in classical Arabic literature. (1997),116-17.

Nimet Allam Hamdy, “The Development of Nude Female Drawings in Persian Islamic Painting.” In Akten des VII. Internationalen Kongresses für Iranische Kunst und Archäologie, München (Berlin: D. Reimer. 1979), 431-432

Niẓāmī Ganjavī, and Julie Scott Meisami. The Haft Paykar : a Medieval Persian Romance Oxford [England] ;: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Omidsalar, M. (1995). “ DĪV”. Encyclopædia Iranica. VII/ 4, pp. 428-43; available online at: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/div. (accessed online on December 9th 2019).