Autonomy and Power:

Maya Scribes

Sarah Henzlik

Citation: Henzlik, Sarah. “Autonomy and Power: Maya Scribes.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, January 7, 2021.

Abstract: Compounded by assumptions of ‘common knowledge’ and skepticism of ‘pagan’ traditions, an incomplete understanding remains about the lives, training, and role of Maya scribes due to the destruction of prior accounts. By analyzing representations of scribes created by scribes across a variety of extant media including written accounts in codices, vessels, and incised bones, scholars can uncover the complex and nuanced standing of scribes. While pictorially depicted with less stature and prestige than rulers, scribes were revered in the court and possessed implicit power over rulers, and by extension, their subjects, as it was the scribes who wrote the first draft of their group’s legacy, recorded significant ritual practice, and acted as a conduit to ruling legitimacy by recording genealogy and divine history. The following paper employs visual analysis and primary source research to underscore its argument that Maya scribes possessed autonomy and power, and a strong connection to the divine that manifested through their behavior, status, and sense of self.

Key words: Art History; Museum Studies; Mesoamerica; Maya; Scribes

When Spaniard Bernardino de Sahagún arrived in the christened “New Spain” in 1529, the trained missionary and would-be ethnographer was prepared to document the amazing, the exotic, and the shocking trappings of the “natives” for the consumption of his financial backers— the Catholic Church and the Spanish Monarchy.[1] As such, elements of Mesoamerican life, such as the figure of the scribe in court, that bore resemblance to life back home did not warrant ample mention in Sahagún’s commissioned work, The General History of the Things of New Spain, widely-known as the Florentine Codex. By contrast, the likes of feather workers, the skilled artisans who performed intricate work, were new to Sahagún, and appear extensively in commissioned works, presenting Mesoamerican life from a Eurocentric point of interest. As a result, compounded by assumptions of ‘common knowledge’ and skepticism of ‘pagan’ traditions, an incomplete understanding remains about the lives, training, and role of scribes due to the destruction of prior accounts.[2] By analyzing representations of scribes crafted by scribes across a variety of extant media, including written accounts in codices, vessels and incised bones, scholars can uncover the complex and nuanced standing of scribes. While pictorially depicted with less stature and prestige than rulers, scribes were revered in the court and possessed implicit power over rulers, and by extension their subjects, as it was the scribes who wrote the first draft of their group’s legacy, recorded significant ritual practice, and acted as a conduit to ruling legitimacy by recording genealogy and divine history. Valued fixtures of royal court proceedings, Maya scribes possessed autonomy and power, a strong connection to the divine that manifested through their behavior, status, and sense of self.

Introduction to the Maya Belief System

Ritual practice was very important to the Maya; from dance to sacrifice, monuments to written records in codices. The Maya believed in the importance of the natural world. Agriculture, for its life-giving properties, was sacred and said to have many similarities to the human life cycle. As Mary Miller and Karl Taube discuss, “humans [are] like maize and flowers that are planted on the surface of the earth, born to die, but containing the seed of regeneration.”[3] Maya rulers were recognized as divine in life and in death. When depicted in portraiture, living Maya rulers often appear as the Maize God, a powerful creation deity, who is also known as God E. In 1904, Paul Schellhas devised the current classification system among art historians and archaeologists of Maya gods called the Schellhas system. In the Schellhas system, gods are given a name that corresponds with a letter of the English and Spanish alphabet. In this paper, the following gods are discussed: God N (a four-part god who is responsible for holding up the sky and often has a turtle or conch shell on his back) and God L (an elderly merchant god of the underworld who is often shown with trading goods such as feathers, an owl and a broad-brimmed headdress). In addition, Hun Chuen (1 Monkey) and Hun Batz (1 Howler) are the sons of the Maize God and half-brothers to the sacred Hero Twins, Hunahpu (Hunter) and Xbalanque (Jaguar Deer). Hun Chuen (1 Monkey) and Hun Batz (1 Howler) are the patron gods of art, writing, and calculating and considered gifted and industrious. Typically depicted in monkey form, this monkey likeness is often transferred to scribes, who were responsible for writing. As a result, scribes enjoyed a powerful, positive association with the divine.

What was a scribe? What could they do? How do we know?

The following analysis seeks to focus on the scribes of the Maya with the understanding that the records of Mixtec and Aztec scribes help to underscore knowledge of the discipline due to the small number of remaining extant media available throughout the region. The scribe was an occupation and a royal court position, occupied by individuals from the upper echelons of Maya society. Kevin Johnston finds that in some cases, scribes were the siblings or offspring of rulers to cement loyalty in the royal court, [4] with scribal elite workshops attached to royal residential compounds.[5] When conceptualizing Maya society into three classes: Royal (the ruler and his family), the Upper Class (individuals trained to be warriors, feather workers and scribes) and the Lower Class (manual laborers, among others), scribes enjoyed the privileges of a financially and socially stable life. Unlike the majority of individuals throughout Mesoamerica, including, in some cases, the ruler, scribes were literate and trained to read, write and understand the complex system of Maya hieroglyphs by trained practitioners.

In this tradition, scribes learned directly from God N himself, a four-part god who is responsible for holding up the sky and often has a turtle or conch shell on his back (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1) God N Trains Scribes (Vessel 56), Classic, Maya, Ceramic, H 9.7 cm; D 10.2 cm.

Justin Kerr, [K 1196], Justin Kerr Maya Vase Archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

Later, scribes learned directly from the patron gods of scribes, the Maize God’s sons, the Howler Monkeys.[6] With this knowledge came great responsibility to perform the daily expectations of a scribe—including maintaining a ledger of recording court events such as rituals, weddings, births—as well as communicating with rulers and acting as a conduit to spiritual leaders and ritual performers.[7] Effectively, without scribes, rulers would have lacked a clear record of the nuances of history and ritual practice. That being said, many narratives and customs were passed down through oral tradition; the scribes supported these traditions by recording them materially on a variety of media, including on bones and vessels.[8] Taken together, oral and written histories documented by scribes for posterity remain a valuable source for learning about the nuanced positions occupied by scribes.

Much of what is currently published in the field on the education and position of scribes is based on extant media; in effect, scribes writing about scribes. Only a small sample has been discovered, complicated by a twofold result: first, the Mesoamerican practice of destroying records within a period as a cyclical tradition and second, the conquistadors’ work of destroying Mesoamerican records of life, particularly records deemed “pagan” and “devious” such as records of non-Christian religious practice. For instance, after the infamous burning of more than twenty-eight codices in an auto-da-fé ceremony, Diego de Landa, a Spaniard and the first bishop of Yucatan stated:

These people also made use of certain characters or letters, with which they wrote in their books their ancient matters and their sciences and by these and by drawings and by certain signs in these drawings, they understood their affairs and made others understand them and taught them. We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction.[9]

Mesoamerican scholars confidently point to records of the training of warriors and feather workers, such as those depicted in the Florentine and Mendoza codices and on extant media such as vessels, as viable proxies to the training of scribes as they hailed from a similar social standing.[10] Vessels represent the most numerous of the extant media, which may bias the analysis.

Artistic and Pictorial Representations of Scribes: How are scribes rendered in art?

Miller and Taube find that male children born during the Trecena 1 Monkey calendar period were most likely (and suited) to be artists and scribes.[11] In the same vein, Friar Diego Durán, a sixteenth-century Spanish priest who commissioned the Durán Codex, recalls how a “brush was placed in the hands of children whose birth signs indicated they were going to be painters during birthing rituals.”[12] These accounts help to support the position that the vocation of the scribe was considered to be highly symbolic and ritualistic as evidenced by the way in which children were ordained into their destined calling to support the empire.

Education of male children was largely determined by social class. Boys born into nobility were trained at a calmecac school from ages six through thirteen years old in the skills of woodcarving, writing, painting, and feather work, while most commoner males trained to be warriors within their calpulli (city-states) beginning at age fifteen.[13] Some commoner boys identified as gifted were granted the opportunity to matriculate at a calmecac.[14] In addition to some combat training, the calmecac prepared young men for roles as priests as well as government officials, such as scribes in the royal court. Trained artisans also could matriculate to become a tolteca, a master craftsman who specialized in one medium.[15] Educational institutions were integral in promulgating the Mesoamerican values of conforming, obedience and decorum as well as offering a strong basis in singing and dancing rituals,[16] a significant aspect of everyday life.[17] Milbrath asserts that scribes offered an integral connection between dancers preparing to perform and the continuation of proud traditions and lineages. Milbrath also states that scribes were likely vibrant focal points in ritual ceremonies that promoted artisans and cultural celebration.[18] This underscores the importance of the holistic training of the scribe, positioning him to be well-versed in a variety of subjects both clerical and religious to support the multi-faceted royal court and community.

When investigating the curriculum of burgeoning Maya scribes, scholars find visual evidence that training included instruction in quantitative and qualitative subjects, namely record keeping and religious history. Tozzer notes that second sons of lords were taught by priests in subjects such as computation of the calendars, the fateful days and seasons as well as festivals and ceremonies, how to administer sacraments, methods of divination and prophecies.[19] Additionally, scribes even received education on cures for diseases and antiquities on top of their primary training on reading, writing and illustrating in the complex system of Maya hieroglyphs.[20] As such, scribes’ intense intellectual training molded them into valuable assets for their communities. As direct successors of God N himself in the art of writing, scribes did not take this training lightly: rather, they were inclined to self-affirm their vocation as a duty. This representation could take many forms, some of which survive on extant vessels.

Vessels

Extant vessels demonstrate the scribe’s omnipresence in the royal court. Among extant vases, there are five primary modes of representing scribes; the first three modes depict the scribe in humanoid form: (1) the scribe seated at the ruler’s feet, (2) the scribe working without the ruler (3) the scribe as the Maize God. The second set of scribal representations assume zoomorphic form: (4) the scribe as a Howler Monkey (God) and (5) the scribe as a supernatural, wise rabbit.

Fig. 2) Scribal Work Vase, Late Classic, Maya, Polychrome ceramic, H: 21.5 cm; D: 13.2 cm.

Justin Kerr, [K 0717], Justin Kerr Maya Vase Archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

To address the first mode, the scribe seated at the ruler’s feet, we turn to one scene depicted on the Scribal Work Vase (Fig. 2). Directing our attention to the scene on the far left, there are two figures in the scene. The leftmost figure seated on a platform or throne with an elaborate headdress, possibly in the style of a tonsured hairstyle in an allusion to the Maize God, is likely a Maya ruler. The ruler is seated cross-legged with his arms extended as a breath of life icon appears, perhaps in part of a spoken proclamation. The ruler appears to be a deep ruddy brown except for a jaguar-pelt-style kilt. By contrast, the figure seated to the right of the ruler on the ground appears to be a royal court scribe. The scribe is seated on the ground, his hierarchical structure is lower than the ruler, a show of his subordination in ranking to the ruler.[21] While not as elaborate as the ruler’s, the scribe also wears a headpiece, possibly a “spangled” turban and is seated cross legged amidst what appear to be a variety of ritualistic court objects.[22] The scribe is depicted at work, possibly recording what the ruler is dictating; the scribe’s body is inclined toward the media object (perhaps a codex or a mask) by leaning forward with hands bent at work.[23] The scribe’s face appears symbolically painted in shades of ruddy brown and white with a kilt of what appears to be an animal print. A curved object appears close to the scribe’s mouth; given that the ruler is speaking, it is unlikely that it is a breath of life. Rather, it may be a tusk or proboscis of the zoomorphic sort, seen on a monkey akin to zoomorphic representations to be discussed later in this section.

The scene on the right in Scribal Work Vase (Fig. 2) offers a glimpse entirely focused on the scribe at work without the ruler. In contrast to the headdress worn in the presence of the ruler, the scribe in this scene wears a much more elaborate headdress. This headdress appears to have tonsured strands akin to the Maize God’s hairstyle, an allusion to the positive characteristics associated with the Maize God such as wisdom, knowledge, sustenance, and reverence. Significantly, the scribe appears to be working while seated on a raised platform. This platform appears at the same height as the ruler’s platform in the rollout: perhaps signaling that in the scribe’s realm (most likely a scribal workshop), the scribe themselves is a powerful individual with divine holdings.

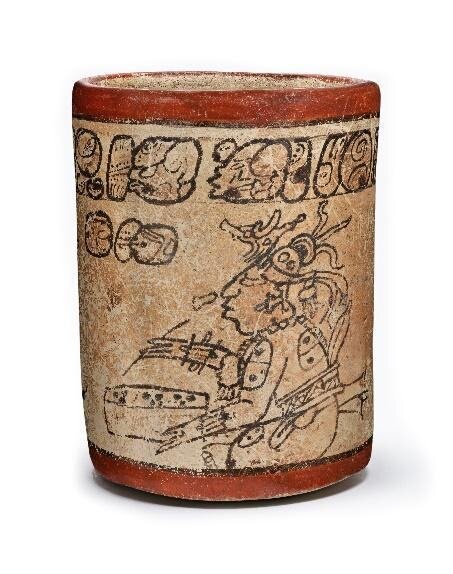

Fig. 3) Codex-Style Cylinder Vessel with Scribes, Maya Guatemala or Mexico, Northern Petén or Southern Campeche. 650-800 CE, Slip-painted ceramic, 5 3/10 x 4 x4 in.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, anonymous gift (M.2010.115.562) photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

In Codex-Style Cylinder Vessel with Scribes (Fig. 3), two humanoid scribes are depicted working without the presence of a ruler, likely in a scribal workshop. This representation is on a vase in a technique called “codex-style” by Michael Coe as his research posits that the artists who created these vessels were codex painters accustomed to inscribing “folding-screen books that the Maya made from bark paper coated with stucco.”[24] Megan O’Neil found that portable media such as codex-style vessels were used to preserve and share information as well as to tell stories.[25] On this vessel, the scribe on the left holds a book and writing utensil or reed pen while the scribe at right holds a shell paint pot. Both figures wear abundant, most likely jade jewelry, including a royal, perhaps ajaw, jewel on the forehead. O’Neil notes that as artists and scribes were esteemed members of ancient Maya society, they were referred to as its'aat (wise person) or named by their practice.[26] For example, aj tz'ihb (writer, painter) referred to those who painted with a brush or quill.[27] But even when shown as human, scribes display characteristics such as mirror signs on their skin or water lilies (stand-in for quill pens) in their headdresses, suggesting a supernatural nature or connections with the supernatural.[28]

Fig. 4) Depiction as Maize God as Scribe (Vessel 69), Classic, Maya, Ceramic, H 12.2 cm; D 9.6 cm.

Justin Kerr, [K 1185], Justin Kerr Maya Vase Archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

If these representations of the scribe associated with many reverent signs were not enough, there are many instances in which the Maize God himself is depicted as a scribe, associated with knowledge and power over every day (Fig. 4). Except for the Sun God and Ometeotl (God of Duality), the Maize God was the most important god throughout Mesoamerica and a key player in creation myths as corn was a staple of the harvest.[29] In Depiction as Maize God as Scribe (Fig. 4), the Maize God, in the form of a tonsured young lord, can be seen depicted as a scribe, associated with knowledge. In this scene, the tonsured young lord is shown at left writing in a codex. The scribal figure on the left can be identified as the Maize God due to the significant iconographic traits of an elaborate tonsured hair style with the telltale long strands akin to an ear of corn, the sloping forehead associated with nobility and the ornate jade jewelry.[30] Notably, the scribe to the right lacks these physical characteristics; instead, exhibiting facial features similar to those associated with the “Monkey-Man” transformation.

While there are prevalent examples of scribes depicted as humans on extant media, one of the most common depictions of scribes presents them in zoomorphic, animal-form, chief among them in ‘simian,’ howler monkey appearance. Scholars point to this representation as an embodiment of the story of two of the Maize God’s sons, Hun Chuen (1 Monkey) and Hun Batz (1 Howler), patron gods and supporters of the arts, musicians, singers, sculptors, painters, and scribes.[31] Hun Chuen and Hun Batz were stepbrothers of the Hero Twins, Hunahpu (Hunter) and Xbalanque (Jaguar Deer) and shared the house of their common grandmother, Xmucane. Francis Robsicek notes that the two sets of brothers did not get along well, and after a disagreement over the trophies of the Hero Twins’ hunts, the Hero Twins persuaded their brothers to climb a tree, where they were transformed magically into monkeys. As the Popol Vuh recalls:

They once become animals And turned into monkeys Because they just boasted And mistreated their younger brothers

1 Monkey And 1 Howler, The sons Of 1 Hunter They became flutists; They became singers; They became writers; They also became carvers [32]

As such, scribes appear frequently on extant media embodying their patron gods, the howler monkeys.

Fig. 5) Scribes as Howler Monkeys (Vessel 60), Classic, Maya, Ceramic, H: 14.0 cm; D: 11.5 cm.

Justin Kerr, [K 1787], Justin Kerr Maya Vase Archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

For instance, in Scribes as Howler Monkeys (Fig. 5), two young male scribes seated under a “sky band” work on codex-style vases. The scribe on the left appears to have large “Midas” deer-like ears with double-dot akbal symbols, identified by Michael Coe as associated with wisdom as the “extra ears” allow for advanced listening.[33] Notably, both figures have ‘simian’ or monkey-like mouths. Both figures appear to wear the stone, perhaps jade, jewelry up and down their front and back, with water lilies (representing quill pens) in their headdresses connoting their position of status.[34] While other representations show monkey scribes in a more pronounced and “grotesque” manner with exaggerated tusk or proboscis facial features in line with the tradition of Scribal Work Vase (Fig. 2), Francis Robsicek posits that due to the young age of the scribes, this depiction may represent an interim stage of transformation of scribes from entirely human to “Monkey-Man god” to entirely animal.[35] As the scribes mature and hone their craft, their proximity to embodying their divine patron gods will be complete.

Rounding out the fifth trope of depictions of scribes in extant media is the scribe in a second zoomorphic form: as a supernatural, wise rabbit, seen on the much-discussed Princeton Vase (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6) The Princeton Vase. North America, Guatemala, Petén, Mirador Basin, Nakbé region, 670-750 CE. Maya. Ceramic with red, cream, and black slip, with remnants of painted stucco, H: 21.5 cm; D:16.6 cm.

Princeton University Art Museum. Museum purchase, gift of the Hans A. Widenmann, Class of 1918, and Dorothy Widenmann Foundation

Here, we see what appears to be a supernatural rabbit kneeling as though he were a scribe recording the events taking place in the scene.[36] Situated in a complex royal court of a ruler or god seated on a throne accompanied by court attendants, the rabbit scribe assumes a kneeling posture with the figure’s weight inclined forward with legs crossed at the ankles and holds a writing utensil as he records the events taking place on a media object. The rabbit is positioned directly below the ruler or god and its eyes are cast up, perhaps to observe the ruler’s actions. Stephen Houston and David Stuart note that this position demonstrates the scribe’s subordination to the ruler.[37] The decision to depict the scribe as a rabbit is symbolic; Mesoamerican tradition regards the rabbit as one of the most favored creatures of the hunt, as well as a symbol of the moon and inebriation.[38] Except for a rabbit-like face and ears, the remainder of the figure’s body is human-like. The body wears a kilt with a textile ornament protruding out the back. The figure’s right hand holds a paint brush, which is poised above what appears to be a vase or vellum-based writing surface to prepare an open codex.[39] Some scholars have identified the enthroned figure as God L, the Schellhas classification of the Maya God of Merchants and Tobacco typically identified with a broad brimmed hat made of owl feathers with an owl flying by.[40] Following this narrative, some representations in Maya art depict a rabbit stealing God L’s hat. In this scene, the staff at the vase’s host institution, the Princeton University Art Museum, asserts that the rabbit scribe has nefarious intentions: the rabbit peers up at God L to spy on him.[41] By associating the scribe in an underworld scene, the scribe’s importance can be traced to the divine, a lauded position of reverence and not solely a clerical, governmental role. This divine association can be traced to the practice of incised bones, as demonstrated in the deified scribe hand at Tikal.

Incised Bones

One such life event inextricably intertwined with scribal practice, religious belief and tradition is the funeral and the process of burial, particularly among the Maya. Here, we focus on one particular burial site identified as Tikal, Burial 116. Presently held by El Museo Morley in El Parque Nacional Tikal in Guatemala is a bone incised with an image of a deified scribe’s hand emerging from an open-mouthed serpent (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7) Incised bone from Burial 116, Tikal. Maya Drawing Museo Morley, Parque Nacional Tikal, Guatemala

Drawing by Linda Schele © David Schele.

Schele Drawing Collection of Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Object Number SD-3539

Photo courtesy Ancient Americas at LACMA (ancientamericas.org)

Showcased with Reverence: Scribes Culminate their Position by Resisting Foreign Intervention with Preservation

Scribes were vital members of support for a ruler and members of the elite in their own right. Whether facing rivals from Mesoamerica or Europe, scribes represented an asset to be reckoned with in the face of enemies. Kevin Johnston, in analyzing representations found at Piedras Negras and Palenque, notes “by capturing his scribes, the victor wounded his enemy.”[54] As a result, scribes were likely sought as targets by enemy warriors for two reasons:

The destruction of enemy scribes as royal persons (potential elite rivals who might otherwise survive the defeat of an enemy king) and

The impact that the elimination of writing services had on the ability of competitors to produce politically powerful and persuasive texts.[55]

Through visual analysis, scholars posit that after capture, scribes were executed for human sacrifice. While other Mesoamerican practices remove the heart when performing human sacrifice, Johnston notes that captured scribes had their fingers mutilated and broken, taking away their ability to write and continue the ruler’s legacy.[56] By devising specific action plans against scribes, it is a sign that rulers and military leaders recognized the power scribes held and sought to strategically eliminate it as they posed a threat.[57]

With the arrival of foreign intervention and conquest, scribes played an important role in preserving their history and customs: with texts such as the Popol Vuh and the Chilam Balam,

scribes made them “not to understand the foreign culture but to defy its authority and preserve indigenous knowledge.”[58] Upon arrival Spanish conquistadors recognized the power of writing among the Maya as well as other Mesoamerican groups and actively punished Maya scribes if they continued to produce Maya script. Maya priests and scribes responded to Spanish authority and oppression by hiding books and deity effigies and obscuring the religious knowledge they contained.[59] As previously mentioned, the Spanish systematically destroyed Maya codices and other written records due to the belief that they promoted non-Catholic belief systems contrary to their agenda. Similar to Bernardino de Sahagún and Antonio de Mendoza, Diego de Landa recognized that for the Spanish to achieve their religious aims, it was important to know about Maya society. As a result, Landa worked with Maya scribe Gaspar Antonio Chi (ca. 1531-1610) to record what Landa thought was a Maya alphabet. Although it was a syllabary, this document played a crucial role in the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphs centuries later.[60] In this case, Chi used his power as a scribe to permeate the linguistic heritage of the Maya in the face of extinction. This was also the case in the Aztec Codex Mendoza; a scribe previously commissioned by the Aztec court to produce the Matricula de Tributos received a commission from the Spanish conquistadors to create the Codex Mendoza.[61] While both scribes likely did not have much of a choice, by accepting the commission, the scribes helped ensure the existence of their cultures for posterity.

In addition to accepting commissions to record for posterity, the scribes who produced the Chilam Balam wrote to actively resist and defy takeover. Megan O’Neil observes one tactic to be writing in Latin letters to assuage suspicion; for instance, in the Chilam Balam, scribes prepared the text in Yucatec Maya and in Latin. Additionally, scribes were able to work within the constraints placed on them by partially copying hieroglyphic codices and adding Christian content, metaphors, and riddles to obscure the traditional knowledge and religious practices. This allowed scribes to preserve knowledge while hiding it from the Spaniards. O’Neil argues that the Chilam Balam was “thus a form of intercultural translation; however, they were made not to understand the foreign culture but to defy its authority and preserve indigenous knowledge.”[62] John Chuchiak describes the scribes’ “graphic pluralism” as a form of resistance to Spanish authority. By writing in Latin letters and hieroglyphs, scribes worked creatively to resist, adapt, and create new identities within the political and social systems formed in the wake of the Spanish invasion.”[63]

Thanks to the active participation of scribes in extenuating circumstances—from the epidemic during the creation of the Florentine Codex to the murder of natives by conquistadores—the tlacuilos (scribes) achieved three quantifiable gains:

They allowed for modern day readers to know the legends and language of the Maya through avenues such as the Popol Vuh (including the Hero Twins and their interactions with their stepbrothers in their ill-fated tree climbing event)[64] and social history of the Maya.[65]

They made sure that elements of the history of the conquest, such as the brutal murder of Aztec citizens at Toxcatl, were never forgotten by representing them in the Codices Aubin and Azcatitlán.[66]

Their agency of representation allowed modern day people to know what they looked like. In the Florentine Codex, there are twenty-two individualized portraits of artists. How they wore their hair, the slant of their chin and their style of clothes can live on.[67]

Conclusion

The nuanced, complex, and storied tradition of the scribe is one of deference to the ruler but also one that saw the ruler at times relying on the scribe’s knowledge, expertise, and skill set to record history, carrying the court forward. Across extant media, we have seen the scribe represented in varying human and animal forms, seated at a ruler or god’s feet, and working resolutely in a workshop. As Barrera Vasquez notes, while scribes trained with an intensity similar to other Maya government roles, being a scribe was not just a day job—it was a revered lifelong identity. When analyzing the sixteenth century Maya Motul Dictionary, the following passage captures the scribe’s lament upon mutilation of his hands and fingernails:

I have no fingernails; I am no longer the person I used to be to, I no longer have power or authority or money; I am no one.[68]

In this regard, the Maya citizen as a scribe can be understood as a “claimed identity,” an act of agency and autonomy in which an individual displays to others as a way of influencing their

perception of a particular self-presentation.[69] Thus, the scribe figure can be considered a negotiation between the secular and supernatural; during their mortal lifetime, scribes and lords closely associated with codices became gods and demigods in their afterlife, allowing for the perpetuation and “circulation” of codices in their godly circles and among mortals.[70] While Sahagún and others may have taken the position of the scribe for granted—nothing more than a subordinate cleric—it is instructive to expand this conception to one of scribes as powerful, autonomous individuals capable of making impactful decisions. Scribes were skilled artisans, integral cultural and ritual figures: and they were proud of it. As a result of being granted respect for their responsibilities, the scribe was inclined to self-affirm this proud title and duty to their empire until his last dying breath.

Endnotes

[1] Diana Magaloni Kerpel, “Painters of the New World: The Process of Making the Florentine Codex,” in Colors Between Two World: The Florentine Codex of Bernardino de Sahagún, ed. Gerhard Wolf and Joseph Connors in collaboration with Louis A. Waldman, (Florence: Villa I Tatti (Harvard University), 2012), 47.

[2] Kerpel 2012, 47.

[3] Mary Miller and Karl Taube. The Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2018), p. 31.

[4] Kevin J. Johnston, “Broken fingers: Classic Maya scribe capture and polity consolidation,” Antiquity 75, June 2001: 380.

[5] Gabrielle Vail, “Scribal Interaction and the Transmission of Traditional Knowledge: A Postclassic Maya Perspective,” Ethnohistory 62, (July 2015): 447.

[6] Francis Robicsek and Donald M. Hales, The Maya Book of the Dead, The Ceramic Codex. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Art Museum, 1981, 126.

[7] John Monaghan, “Performance and the Structure of the Mixtec Codices,” Ancient Mesoamerica 1, no. 1, Spring 1990, 134.

[8] Monaghan 1990, 137.

[9] Robicsek and Hales 1981, xix.

[10] Miguel León-Portilla, “Native Mesoamerican Spirituality…” The Missionary Society of St. Paul, the Apostle in the State of New York, 1980, 88.

[11] Mary Miller and Karl Taube. The Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2018). “scribal gods.”

[12] Elizabeth Morán, “Food in Aztec Ritual,” In Sacred Consumption: Food and Ritual in Aztec Art and Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016, 40.

[13] León-Portilla 1980, 87.

[14] Andrea Gallelli Huezo, “Aztec Codices: Mendoza,” Seminar Lecture, ARTH 418: Mesoamerican Art - Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., March 24, 2020.

[15] Huezo 2020.

[16] Monaghan 1990,” 134.

[17] Miguel León-Portilla, “Native Mesoamerican Spirituality,” 94.

[18] Susan Milbrath and Carlos Peraza Lope. “Mayapan’s Scribe: A Link with Classic Maya Artists,” Mexicon 25, no. 5. October 2003, 122.

[19] Alfred Tozzer as cited Gabrielle Vail, “Scribal Interaction and the Transmission of Traditional Knowledge: A Postclassic Maya Perspective,” Ethnohistory 62, July 2015, 450.

[20] Vail 2015, 450.

[21] Stephen Houston and David Stuart, “The Ancient Maya Self: Personhood and Portraiture in the Classic Period,” Anthropology and Aesthetics 33, Spring 1998, 88.

[22] Michael Coe as cited in Francis Robicsek and Donald M. Hales, The Maya Book of the Dead, The Ceramic Codex, 133.

[23] Robicsek and Hales 1981, 30.

[24] Robicsek and Hales 1981 , xix.

[25] Megan O’Neil, “The Painter's Line on Paper and Clay: Maya Codices and Codex Style Vessels from the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century.” In Toward a Global Middle Ages: Encountering the World through Illuminated Manuscripts, ed. Bryan C. Keene (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019), 125.

[26] O’Neil 2019, 130.

[27] O’Neil 2019, 130.

[28] Milbrath and Lope 2003,121.

[29] Karl Taube, “The Classic Maya Maize God: A Reappraisal.” In Fifth Palenque Round Table 1983, edited by Merle Greene Robertson, San Francisco: The Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, 172.

[30] Taube 1983, 172.

[31] Robicsek and Hales 1981, 125.

[32] Robicsek and Hales 1981, 125.

[33] Michael Coe as cited in Robicsek and Hales 1981, 125.

[34] Milbrath and Lope 2003, 121.

[35] Milbrath and Lope 2003, 121.

[36] Mary Miller and Karl Taube. The Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames and Hudson, 2018. “rabbit.”

[37] Houston and Stuart 1998, 88.

[38] Miller and Taube 2018, “rabbit.”

[39] Houston and Stuart 1998, 94.

[40] Miller and Taube 2018, “rabbit.”

[41] Ceramics, “The Princeton Vase,” Princeton University Art Museum. The Trustees of Princeton University.

[42] Miller and Taube 2018, “serpent.”

[43] Miller and Taube 2018, “serpent.”

[44] Miller and Taube 2018, “serpent.”

[45] Miller and Taube 2018, “serpent.”

[46] Miller and Taube 2018, “serpent.”

[47] Miller and Taube 2018, “serpent.”

[48] Allen Christensen, Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya: The Great Classic of Central American Spirituality, translated from the Original Maya Text. (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007): 20.

[49] Stephen Houston, David Stuart and Karl Taube, The Memory of Bones : Body, Being, and Experience among The Classic Maya. (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2006), 2.

[50] Houston, Stuart, and Taube 2006, 57.

[51] Kevin J. Johnston, “Broken fingers: Classic Maya scribe capture and polity consolidation,” Antiquity 75, (June 2001): 380.

[52] D.Z. Chase and A.F. Chase as cited in Kevin J. Johnston, “Broken fingers: Classic Maya scribe capture and polity consolidation,” Antiquity 75, (June 2001): 381.

[53] O’Neil 2019, 130.

[54] Johnston 2001, 377.

[55] Johnston 2001, 378

[56] Johnston 2001, 376.

[57] Johnston 2001, 376.

[58] O’Neil 2019, 126.

[59] O’Neil 2019, 126.

[60] O’Neil 2019, 126.

[61] Juan José Batalla Rosado, “The Scribes who Painted the ‘Matricula de Tributos’ and the ‘Codex Mendoza,’” Ancient Mesoamerica 18, no. 1 (Spring 2007).

[62] O’Neil 2019, 126.

[63] John Chuciak as cited in O’Neil 2019, 126.

[64] Robicsek and Hales 1981, 125.

[65] Allen Christensen, Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya: The Great Classic of Central American Spirituality, Translated from the Original Maya Text. (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007): 15.

[66] Federico Navarrete, “The Hidden Codes of the Codex Azcatitlán,” Res: Anthropology and aesthetics 45 (Spring 2004): 158.

[67] Diana Magaloni Kerpel, “Painters of the New World: The Process of Making the Florentine Codex,” (Florence: Villa I Tatti (Harvard University), 2012).

[68] Johnston 2001, 379.

[69] Houston and Stuart 1998, 94.

[70] Robicsek and Hales 1981, 126.

Bibliography

Anawalt, Patricia Rieff and Berdan, Frances F. “The Codex Mendoza.” Scientific American 266, no. 6. June 1992, 70-79.

Batalla Rosado, Juan José. “The Scribes who Painted the ‘Matricula de Tributos’ and the ‘Codex Mendoza.’” Ancient Mesoamerica 18, no. 1. Spring 2007, 31-51.

Ceramics. “The Princeton Vase.” Princeton University Art Museum. The Trustees of Princeton University.

Christensen, Allen. Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya: The Great Classic of Central American Spirituality, Translated from the Original Maya Text. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007.

Codex Mendoza. 1553.

Coe, Michael D., Javier Urcid, and Rex Koonz. Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. (Eighth Edition). London: Thames and Hudson, 2019.

Dreiss, Meredith L., and Sharon Edgar Greenhill. Chocolate: Pathway to the Gods. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2008.

Houston, Stephen, and David Stuart. “The Ancient Maya Self: Personhood and Portraiture in the Classic Period,” Anthropology and Aesthetics 33, Spring 1998, 73-101.

Houston, Stephen, David Stuart and Karl Taube. The Memory of Bones: Body, Being, and Experience among The Classic Maya. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2006.

Johnston, Kevin J. “Broken fingers: Classic Maya scribe capture and polity consolidation.” Antiquity 75. June 2001, 373-381.

León-Portilla, Miguel. “Native Mesoamerican Spirituality: Ancient Myths, Discourses, Stories, Doctrines, Hymns, Poem from the Aztec, Yucatec, Quiche-Maya and the Other Sacred Traditions.” 1980. The Missionary Society of St. Paul, the Apostle in the State of New York.

Magaloni Kerpel, Diana. “Painters of the New World: The Process of Making the Florentine Codex.” In Colors Between Two World: The Florentine Codex of Bernardino de Sahagún, edited by Gerhard Wolf and Joseph Connors in collaboration with Louis A. Waldman, Florence: Villa I Tatti (Harvard University), 2012, 46-76.

Martin, Simon. “Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion: First Fruit from the Maize Tree and other tales from the Underworld.” In Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao, edited by Cameron L. McNeil, 154-183. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 2006.

Milbrath, Susan and Carlos Peraza Lope. “Mayapan’s Scribe: A Link with Classic Maya Artists.” Mexicon 25, no. 5. October 2003, 120-123.

Miller, Mary, and Karl Taube. The Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames and Hudson, 2018.

Monaghan, John. “Performance and the Structure of the Mixtec Codices,” Ancient Mesoamerica 1, no. 1, Spring 1990, 133-140.

Morán, Elizabeth. “Food in Aztec Ritual.” In Sacred Consumption: Food and Ritual in Aztec Art and Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016.

Navarrete, Federico. “The Hidden Codes of the Codez Azcatitlán.” Res: Anthropology and aesthetics 45, Spring 2004, 144-160.

O’Neil, Megan, “The Painter's Line on Paper and Clay: Maya Codices and Codex Style Vessels from the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century.” In Toward a Global Middle Ages: Encountering the World through Illuminated Manuscripts, edited by Bryan C. Keene, 125-136. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019.

Robicsek, Francis, and Donald M. Hales. The Maya Book of the Dead, The Ceramic Codex. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Art Museum, 1981.

Sahagún, Bernardino. The General History of the Things of New Spain. 1569.

Taube, Karl, “The Classic Maya Maize God: A Reappraisal.” In Fifth Palenque Round Table 1983, edited by Merle Greene Robertson. San Francisco: The Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, 171-181.

Vail, Gabrielle. “Scribal Interaction and the Transmission of Traditional Knowledge: A Postclassic Maya Perspective.” Ethnohistory 62. July 2015, 445-468.

Vail, Gabrielle, and Christine Hernández. “Introduction to the Maya Codices.” In Re-Creating Primordial Time: Foundation Rituals and Mythology in the Post-Classic Maya Codices. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2013.

![Fig. 1) God N Trains Scribes (Vessel 56), Classic, Maya, Ceramic, H 9.7 cm; D 10.2 cm. Justin Kerr, [K 1196], Justin Kerr Maya Vase Archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ef9fae58544f214e0aee415/1609940095984-K5V4CCCJ7PRTYU6FDBQ1/Fig.1.jpg)

![Fig. 4) Depiction as Maize God as Scribe (Vessel 69), Classic, Maya, Ceramic, H 12.2 cm; D 9.6 cm. Justin Kerr, [K 1185], Justin Kerr Maya Vase Archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ef9fae58544f214e0aee415/1609946262292-VKRCCV6SQS63DVFV7P2F/fig.4.jpg)

![Fig. 5) Scribes as Howler Monkeys (Vessel 60), Classic, Maya, Ceramic, H: 14.0 cm; D: 11.5 cm. Justin Kerr, [K 1787], Justin Kerr Maya Vase Archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ef9fae58544f214e0aee415/1609947345552-9QKP8T62GAY8VDTHQYLN/fig.5.jpg)