Sir John Soane’s Maori Spear

Jessica Romano

Citation: Romano, Jessica. “Sir John Soane’s Maori Spear.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, January 15, 2021.

Abstract: The Sir John Soane’s Museum, an exceptional house museum that holds the personal collection of its namesake, provides a unique context for a case study on objects within museums and personal collections. In focusing on the artefacts in the museum, in particular object number M 607- ‘a Maori spear’, the theoretical framework of object biography is utilised to provide a more holistic understanding of this artefact beyond that presented by the institution that holds it. In considering the changing attitudes and perceptions of objects in the museum, a more comprehensive understanding of this objects’ relevance in the Sir John Soane’s Museum and beyond is discussed.

Key words: Maori spear; Sir John Soane; house museum; object biography

Object meaning is entangled in many different relationships both past and present, which should both be considered in creating comprehensive narratives around objects. By meaningfully approaching collections, objects can be actively foregrounded by the diverse ways in which they are known and entangled in social life. Museum objects provide noteworthy focuses of object biography, as their complex meanings and contexts can be explored through such an approach to enhance the narratives constructed around them. The Sir John Soane’s Museum provides a unique case study as it is memorialized in situ as a museum, conserving the moment in which Sir John Soane’s collection ceased being a collection and began its role as a museum. As such both collection and modern museum impressions can be addressed. By taking a deeper look into the artefacts of the Sir John Soane’s Museum, specifically the Maori spear, one can regard such objects in this museum as more than the simplified notion of interesting oddities or marvels within the larger collection. Rather, information lost in present engagements with this object can be brought to light by considering how objects become invested with meaning and cultural significance within the social networks they belong to.

The Museum in Context

Sir John Soane acquired his collection during the Georgian era while working in London, which included a diverse collection of objects such as architectural fragments and models, plaster casts, classical statuary, natural curiosities including fossils and minerals, paintings, and a library of thousands of volumes. This collection consists of over 40,000 objects as it stands presently. The nature of colonialism occurring in the different regions of the artefacts being collected had an influential role in the creation of collections at the time, as colonialism utilized material culture to create the appearances and performances that it desired.[2] Colonialism also affected the histories of the objects being collected, as is the case in objects of colonial encounter where there are sharp breaks in their biographies or radical resetting of their meaning, through processes of reconceptualization.[3] Collecting was also impacted by developments occurring in anthropology and archaeology as the changes occurring in these disciplines allowed for more power for the middle class, through creating openings for anyone interested in collecting artefacts or providing their own interpretations of them.[4] The creation of Soane’s collection was also occurring during the time at which the modern Museum was coming into being, resulting the hybrid character of his museum, marking the transition of private collections to public museums.

As Susan Millenson argues, Soane abstracted the essence of his sources (the artefacts he collected) and reinterpreted them in a personal manner, as expected in the case of a personal collection. This is shown in their acquisition, induction into his collection, placement within his house and the continuing impact this collection has had on the life histories of these objects. It is made evident that The Sir John Soane’s Museum is not a context in which all aspects of an object’s life are aimed to be understood and shared with the public; but rather objects act more as accessories for the larger ideas of the Museum. This Museum was a product of its times, and as such, the biographies of the objects incorporated into the collection also became reflexive of the time of its construction and founding. “Collections embody worlds of learning but they invariably also constitute a cultural practice vested with meaning, related to individuals understanding of the world around them and their own place within it”;[5] which is made clear in how Soane and the institution of his Museum have presented objects in the collection.

Object Biography

Object biography can encourage one to keep the artefact in focus, while also considering the museum alongside other contexts.[6] The main takeaway from the scholarship on object biography is that information and perceptions are context dependent, and that an object biography allows for the multiple, and changing contexts that contribute to an understanding of an object in present day. Object biography also provides an effective way of allowing for the consideration of multiple perspectives, especially when agency is also considered in conjunction with materiality of a collection. While life history of objects tends to miss the dynamic interplay of people and objects, biography draws a distinction between the commoditization and the singularity of objects, though one must always be aware of the risk of constructing pre-determined narratives that describe objects rather than really understanding them.

In this case study, object biography allows one to cope with the gaps and idleness in an object’s life, therefore allowing for a consideration of the object’s remembered past and its co-created present. As such, the focus of a collection shifts from the overall collection, to that of the object, and back again. Overall, by creating more object biographies via object analysis in museum contexts, one can provide more comprehensive perspectives on the interactions that are layered within the life-histories of objects.

Object M 607: A Maori Spear

This enigmatic item joined Soane’s collection by 1822, as proven by its presence in a view of his first Picture Room.[7] While it has been known to be a part of the collection, there is no knowledge of Soane’s thoughts on this item, and it was only first recorded in the inventory at the time of Soane’s death in 1836, making an understanding of the earlier part of this object’s history difficult to obtain. The complexity of this object comes from the ambiguity of its provenance, acquisition, cultural association, and most importantly, what this artefact essentially is. One is led to believe that it is a Maori spear, while neither its Maori origin nor its use as a spear can be certain. It is clear that the precise origin of this artefact is currently unknown and was unknown by Sir John Soane when he obtained it. Regardless, it is attested to New Zealand as a part of Maori material culture and was presumably acquired from the collections of Captain James Cook. The year 1822 would be an early acquisition for Maori material culture in England and would therefore be significant. Though Soane was not known to have any connection to Captain Cook, it is believed that this object was acquired at a sale held by the Earl of Warwick’s, who was a sponsor of Cook’s voyages.[8]

The connection to Captain Cook’s voyages has significantly impacted how this object has been understood. James Cook, as a collector, represented the artefacts that he acquired in highly decontextualized ways, with ornaments and weapons depicted in such a way that distanced them from Polynesian life.[9] This influenced and continued a tradition of misrepresented objects that are difficult to identify, which contributes to their ‘miscellaneous essence’.

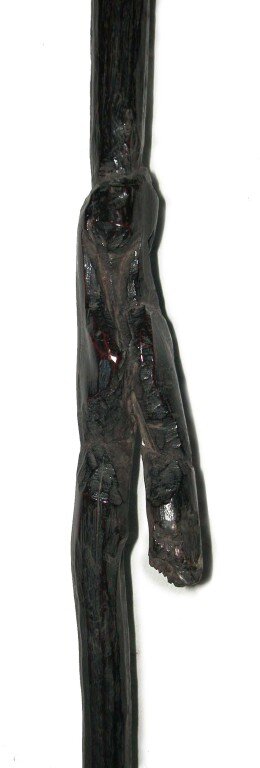

The carvings present on the ‘spear’ were undoubtedly novel at the time in which Soane was actively collecting. While such objects may have been collected for their curious art form, for the Maori people, these objects represented their values and beliefs about the origins of life, death, and ethnic unity, as their artwork heavily draws upon myth and religion.[10] Prior to colonization, the Maori were dependent on organic material through which art could be produced. As such, wood carving was one of the most prominent forms of art in pre-contact periods and has been a continued tradition though time.[11] However, it is notable that none of these significances are discussed in the case of the Soane’s Maori spear. Object M607 is described frequently as a grotesque staff standing around 7 feet tall. While it is evident that the stick itself is made of hard wood, it appears to have been stained at a later point in its life, probably while in the Museum collection, which is a feature that is passed over.[12]

This object has distinguishing deep carvings in a dark, dense wood that is typical of Maori swamp sites.[13] In more recent inclusions to the archive, the carvings themselves are described in more depth as “two strange tiki like figures emerging from a natural wood form,”[14] and appear to exhibit the essential elements of Maori wood carving, though knowledge in this area for pre-contact practices is limited.[15] In the 2018 description of the museum, its position, acquisition date, and its description as a ‘grotesquely carved walking stick’ is all that is mentioned.[16] It is not included in the 1988 or 1835 published descriptions of the museum.

Figure 1. The ‘spear’ end of the Maori Spear, where the majority of the carvings are located. A Maori spear or harpoon, n.d, Photo: © Courtesy of the Trustees of Sir John Soane’s Museum.

In correspondences with Roger Neich, the curator of ethnology at the Auckland War Memorial Museum and professor of anthropology at The University of Auckland, it is suggested that the ‘spear’ was more ceremonial than practical in nature, and further suggests the possibility that it was used as a parrot perch. Though still puzzled by the object, he advocates that this artefact is undoubtedly Maori and places it as being from the East Coast of New Zealand.[17] Contrary to this, Bruce Simpson, of the tribes Nagti Raukawa and Muaupoko, who also works in Maori education, argues that it is in fact not ceremonial, but rather a whaling spear.[18] Overall, it is odd that this object would have lost its history so soon after arriving in England. The lost knowledge of this artefact’s history prior to its inclusion in Soane’s collection is not attainable, which has contributed to confusion in the interpretation and presentation of this artefact. This is especially notable in the changes in identification from staff to spear. There is a significant difference between a staff and a spear, in that a spear implies its use as a weapon, while a staff allows for the possibility of other more utilitarian use. These identifiers create different ideas of how this artefact was used in the past and how it continues to be understood in relation to Maori culture. According to Neich, Maori spears were all made to thrust in close proximity, which is not what this object was crafted to do, though the barbed end appears to suggest a more practical use which coincides with known Maori spears in the University of Cambridge’s collection.[19]

A unique phase of this object’s narrative is when it was identified as the walking stick of the Guy of Warwick. The Guy of Warwick was a 10th century English hero figure whose story, more myth than history, contains mythic monsters of English folklore, quests, and adventure.[20] The amount of power that the Museum and its curators have had in defining objects in the collection, is exceptionally showcased in this example, which is derived from one of the inventory entries.[21] During the time that it was identified as Guy of Warwick’s walking staff, this object was understood to belong to a completely different culture, associated with different mythical ideologies, and defined by a different intention of use. Interestingly, this takes up a large part of the object’s description provided to visitors.

As the identification of this artefact changed throughout its years in the Museum, so did its location. From its initial spot in the original picture room, it was moved into the Colonnade around the time of Soane’s death, which was then followed by a move to the main entrance in 1906. The spear is presently located on the south side of the colonnade, in a recess to the right of a cupboard that contains classical frieze fragments. The majority of the surrounding artefacts are classical in nature and the object itself is hidden behind other objects, making it easily overlooked. Its placement in the museum is more a result of the picturesque aesthetic that Soane had in mind, and most importantly of his taste for narrative.[22] This positioning also further reflects the lack of attention this artefact has received in comparison to other main items in the collection, such as the Sarcophagus of Seti I, though the lack of established information also contributes to a less developed representation and understanding of this object.

Figure 2 . A closer picture of the handle section of the Maori spear and the carvings on it. A Maori spear or harpoon, n.d, Photo: © Sir John Soane’s Museum, London Photo: © Courtesy of the Trustees of Sir John Soane’s Museum.

Concluding Thoughts

As has been outlined in this case study, collections have the ability to recontextualize objects, but also to provide a context in which objects can be further examined to answer specific investigations. Recontextualized objects are inherently flexible; this artefact in particular has undergone transformations to its identity and meaning when becoming a part of Soane’s collection, presented in a way that highlights traits important to Soane, leaving others lost and ignored. Many collections from the 19th century and earlier had very poor documentation, though there has been an attempt to resolve this, as noted throughout the Museum’s archive.

While it is discussed to a degree in the archive, provenance is not something provided as essential to interacting with these objects. In the cases of the Maori spear, there is much information that is unknown, including essential provenance. What this case study highlights as true for artefacts apart of this collection is that the collection does not displace attention to the past; rather, the past is at the service of the collection and lends authenticity to it.[23] Their primary operations are aesthetic and fictional rather than didactic, therefore making these objects relevant to the collection.

Endnotes

[1] Joshua Bell, “A Bundle of Relations: Collections, Collecting, and Communities,” Annual Review of Anthropology 46 (2017).

[2] Chris Gosden and Chantal Knowles, Collecting colonialism: material culture and colonial change (Oxford: Berg, 2001).

[3]Chris Gosden and Yvonne Marshall, “The cultural biography of objects,” World Archaeology 31, no.2, (1999) ; Bell 2017

[4] Chris Gosden, Alison Petch and Frances Larson, Knowing things: exploring the collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum 1884-1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 54.

[5] Stefanie Gänger, Relics of the Past: The Collecting and Study of Pre-Columbian Antiquities in Peru and Chile, 1837-1911 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 7.

[6] Alice Stevenson, Emma Libonati and John Baines, “Introduction—object habits: Legacies of fieldwork and the museum,” Museum History Journal 10, no.2, (2017): 115.

[7] Inventory Entry by Bailey, George, 1837, M607 Maori Spear, Sir John Soane’s Museum Archive, London, England.

[8] Inventory Entry by anon., M607 Maori Spear, Sir John Soane’s Museum Archive, London, England.

[9] Nicholas Thomas, “Licensed Curiosity: Cook’s Pacific Voyages,” In The Cultures of Collecting, ed. John Elsner and Roger Cardinal (London: Reaktion Books, 1997) 116-36.

[10] D Hicks, “People of wood,” The World & I 15, no.12, (2000):174–83.

[11] Caroline Phillips, Dilys Johns and Harry Allen, “Why did Maori bury artefacts in the wetlands of pre-contact Aotearoa/New Zealand,” Journal of Wetland Archaeology 2, no.1, (2002): 39–60.

[12] Inventory Entry by anon., M607 Maori Spear, Sir John Soane’s Museum Archive, London, England, United Kingdom.

[13] Rod Wallace, “A Preliminary Study of Wood Types Used in Pre-European Maori Wooden Artefacts,” In Saying So Doesn't Make It So: Papers in Honour of B. Foss Leach, ed. Doug G. Sutton (Dunedin: New Zealand Archaeological Association, 1989) 222-32.

[14] Inventory Entry by anon., M607 Maori Spear, Sir John Soane’s Museum Archive, London, England, United Kingdom.

[15] Hicks 2000, 174–83.

[16] Sir John Soane’s Museum, Sir John Soane's Museum: A Complete Description, 13th ed (London: Sir John Soane's Museum, 2018).

[17] Email correspondence with Helen Dorey by R. Neich, 2008, M607 Maori Spear, Sir John Soane Museum Archive, London, England.

[18] Email correspondence with Helen Dorey by B. Simpson, 2012, M607 Maori Spear, Sir John Soane’s Museum Archive, London, England.

[19] Email correspondence with Helen Dorey by R. Neich, 2008, M607 Maori Spear, Sir John Soane Museum Archive, London, England ; Wilfred Shawcross,“The Cambridge University Collection of Maori Artefacts Made on Captain Cook’s First Voyage,” The Journal of the Polynesian Society 79, no.3, (1970): 305–48.

[20] “Guy of Warwick: A Very English Hero,” Our Warwickshire, Accessed June 19, 2019, https://www.ourwarwickshire.org.uk/content/article/guy-warwick-english-hero

[21] Inventory Entry by anon., M607 Maori Spear, Sir John Soane’s Museum Archive, London, England, United Kingdom.

[22] Sophia Psarra, “Soane Through the Looking-glass,” In Architecture and Narrative: The Formation of Space and Cultural Meaning, ed. Sophia Psarra (London: Routledge, 2009) 113.

[23] A.R. Blount, “Sir John Soane's Museum: changelessness and change,” MSc diss., (University College London, 2005) 8.

Works Cited

Anonymous. Inventory Entry, M607 Maori Spear. Sir John Soane’s Museum Archive, London, England, United Kingdom.

Bailey, George. Inventory Entry. 1837. M607 Maori Spear. Sir John Soane’s Museum Archive, London, England, United Kingdom.

Bell, Joshua. “A Bundle of Relations: Collections, Collecting, and Communities.” Annual Review of Anthropology 46 (2017): 241-59.

Blount, A.R. “Sir John Soane's Museum: changelessness and change.” MSc diss. University College London, 2005.

Gänger, Stefanie. Relics of the Past: The Collecting and Study of Pre-Columbian Antiquities in Peru and Chile, 1837-1911, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Gosden, Chris, Alison Petch and Frances Larson. Knowing things: exploring the collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum 1884-1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Gosden, Chris, and Knowles, Chantal. Collecting colonialism: material culture and colonial change. Oxford: Berg, 2001.

Gosden, Chris. and Marshall, Yvonne. “The cultural biography of objects.” World Archaeology 31, no.2, (1999): 169–78.

Hicks, D. “People of wood.” The World & I 15, no.12, (2000):174–83.

Neich, R. Email correspondence with Helen Dorey. 2008. M607 Maori Spear. Sir John Soane Museum Archive, London, England, United Kingdom.

Our Warwickshire. “Guy of Warwick: A Very English Hero.” Accessed June 19, 2019. https://www.ourwarwickshire.org.uk/content/article/guy-warwick-english-hero

Phillips, Caroline, Dilys Johns and Harry Allen. “Why did Maori bury artefacts in the wetlands of pre-

contact Aotearoa/New Zealand?” Journal of Wetland Archaeology 2, no.1, (2002): 39–60.

Psarra, Sophia. “Soane Through the Looking-glass.” In Architecture and Narrative: The Formation of Space and Cultural Meaning, edited by Sophia Psarra, 111-135. London: Routledge, 2009.

Shawcross, Wilfred. “The Cambridge University Collection of Maori Artefacts Made on Captain Cook’s First Voyage.” The Journal of the Polynesian Society 79, no.3, (1970): 305–48.

Simpson, B. Email correspondence with Helen Dorey. 2012. M607 Maori Spear. Sir John Soane’s Museum Archive, London, England, United Kingdom.

Sir John Soane’s Museum. Sir John Soane's Museum: A Complete Description. 13th ed. London: Sir John Soane's Museum. 2018.

Stevenson, Alice, Emma Libonati and John Baines. “Introduction—object habits: Legacies of fieldwork and the museum.” Museum History Journal 10, no.2, (2017): 113–26.

Thomas, Nicholas. “Licensed Curiosity: Cook’s Pacific Voyages.” In The Cultures of Collecting, edited by John Elsner and Roger Cardinal, 116-36. London: Reaktion Books, 1997.

Wallace, Rod. “A Preliminary Study of Wood Types Used in Pre-European Maori Wooden Artefacts.” In

Saying So Doesn't Make It So: Papers in Honour of B. Foss Leach, edited by Doug G. Sutton, 222-

32. Dunedin: New Zealand Archaeological Association, 1989.