Encountering Eurocentric Beauty Ideals and Childhood Identity Formation in Collages by Deborah Roberts

Madi Shenk

Citation: Shenk, Madi. “Encountering Eurocentric Beauty Ideals and Childhood Identity Formation in Collages by Deborah Roberts.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, November 18, 2022.

Abstract: Using Deborah Roberts’ photocollage works as a lens, this article contemplates the influence of Eurocentric standards of beauty and stereotypes of Blackness on identity formation as represented by the child subject. Deborah Roberts reappropriates found images and materials from magazines, the internet, and her daily life to bring attention to the historic and continued treatment of the Black body within the realm of cultural production and to the vulnerability of children to the resulting conditions of objectivity and suppression. Theories of intersectionality highlight that women and children are susceptible to multiple layers of oppression as part of a minority race and subordinated gender.[1] Roberts’ focus on children brings attention to another regularly overlooked layer of subjugation and bias, as young people’s identities are in a highly developmental state that is often the most susceptible to ideas promoted by the masses. By emphasizing and subverting the original intentions of her materials and reinventing them as works of fine art, Roberts gives power back to her young Black subjects.

Keywords: collage, colorism, Black identity, Deborah Roberts, childhood identity

Figure 1: Deborah Roberts, A Conversation with Beauty, 2017, mixed media and found photocollage on paper, 30 x 22 in. Courtesy of the artist.

In her 2017 work A Conversation with Beauty (Fig. 1), Austin, Texas-based artist Deborah Roberts presents the viewer with a composite body set against a stark white background. The viewer’s efforts to understand the identity of the subject are hindered by the disjointed pieces that make up her body. Photographic fragments of limbs, facial features, and clothing carefully cut from various archives, magazines, books, and online resources are pieced together to create a legless childlike figure. The subject’s youth is emphasized by the roundness of her cheeks and the playful styling of her short black hair complete with a red and white striped bow. While her grayscale components resist an immediate, racialized reading, a closer examination reveals a combination of body parts taken from both Black and white bodies. The right arm is lighter and larger in scale than the left. The area surrounding her eye in the ovular fragment on her face is lighter than the rest of her complexion. The barely discernable appearance of two ears, one of which optically blends with her hair, further complicates the subject. Is that even ‘her’ face, or is her true face hidden under a mask? Through choice inclusions and exclusions of color, Roberts draws our attention to specific zones within the layered image; the patterned skirt and bow, the golden yellow embellishing her nails and pigtails, and the pinkish complexion of the face garnering her attention.

Robert’s photocollages from the 2010s prominently feature young Black girls, pieced together using various media sources and bisected with recognizably Caucasian body parts. The title of A Conversation with Beauty alludes to the subject’s dilemma as she appears to be playing “dress-up,” a familiar game in which children imagine alternate appearances and identities for themselves. Nestled under her left arm is a portion of a head, interrupted at the neck and face, leaving only dark curly hair and an ear. The chromatic face which she holds up to meet her gaze, with its boldly lined and mascaraed eye, clearly stands out in relation to the grayscale pieces that make up her own. The straight edge on the rear side of the face mimics the shape of a mask. The child appears to be contemplating the options at hand and the possibility of a different identity. As the title suggests, this play with appearance has turned into an exercise in defining beauty. The viewer might ask themselves, does the child consider herself beautiful? Does she wish the white woman’s face that she carefully inspects belonged to her?

Using Deborah Roberts’ photocollage works as a lens, I contemplate the influence of Eurocentric standards of beauty and stereotypes of Blackness on identity formation as represented by the child subject. Deborah Roberts reappropriates found images and materials from magazines, the internet, and her daily life to bring attention to the historic and continued treatment of the Black body within the realm of cultural production and to the vulnerability of children to the resulting conditions of objectivity and suppression. Theories of intersectionality show us that women and children are susceptible to multiple layers of oppression as part of a minority race and subordinated gender.[2] Roberts’ focus on children brings attention to another regularly overlooked layer of subjugation and bias, as young people’s identities are in a highly developmental state that is often the most susceptible to ideas promoted by the masses. By emphasizing and subverting the original intentions of her materials and reinventing them as works of fine art, Roberts gives power back to her young Black subjects.

The artistic strategy of incorporating photographic materials from mass media sources for social commentary is often associated with early twentieth-century avant-garde movements like Dadaism, in which artists responded to the atrocities of war and bourgeois culture by presenting the public with collaged distortions of mass communication materials. The use of photographs disrupts the assumption that photography and news sources present an objective reality and allows artists to subvert the messages promoted by capitalist and political elites. In the decades since Dadaism, artists like Romare Bearden, Betye Saar, Hank Willis Thomas, and Ellen Gallagher have embraced strategies of collage, cutting and pasting photographs, and found objects to emphasize their manipulative and stereotyping properties. Saar states, “[t]hese manufactured images and objects often were…the only source of how we saw ourselves,” emphasizing the psychologically damaging implications of these materials.[3] Caroline A. Brown explains that Black corporeality in America is informed by the history of its representation and treatment. As a result, Black women operating in the world today not only deal with subjugation in the present, but also the legacy of oppression that America is built on.[4] Artists like Roberts extract materials from their original contexts and recombine them in strategic ways to bring attention to problematic histories of representation that are often overlooked. In doing so, they reveal the methods by which racial stereotypes and Eurocentric ideals are upheld in popular discourse.

Growing up in Austin, Roberts was exposed to the types of racialized influences that negatively affect Black women and children all over the United States. She experienced racism first-hand as a Black child growing up in the 1960s, recalling

I remember going to the sixth grade as the only Black in my class. I went to a predominantly white school. I was young; these were formative years when you are trying to determine who you are and how to move forward. My person became the object of ridicule— my hair, my clothes. I was treated as an interloper, as if I didn't belong.[5]

Up to the 2010s, Roberts’ works largely focused on figurative painting of Black subjects in idealized contexts. After entering the MFA program at Syracuse University in 2011, she shifted to collage, emphasizing photographic depictions of children.[6] Roberts’ work brings attention to white beauty ideals, the persuasive effects of advertising materials and how they are especially detrimental to vulnerable demographics such as young Black girls during highly developmental periods of their lives. The artist began using an image of her eight-year-old self as a central element in some of her earliest multimedia and collage works. In works like Hoodratgurl and Girl with Pink Face, both from 2011, Roberts adorns her childhood visage, sporting cat-eyeglasses and pigtails tied up in bows, as a means of highlighting her internal struggle with identity. In Hoodratgurl, she has used a wash of warm brown paint for her face and shoulders, obscuring her facial features, as well as deep black for her hair that drips down from her pigtails. The smiling purity of the girl in the photo is countered by red lettering spelling the words “hood,” “rat,” and “gurl.” Despite her youth and innocence, her character risks being condensed to this one phrase.

Figure 2: Deborah Roberts, Miseducation of Mimi, 2014, collage and mixed media on paper, 17 x 14 in. Courtesy of the artist.

Since 2011, children have continued to be a prevalent subject in Roberts’ works. In Miseducation of Mimi (2014) (Fig. 2), part of a series of the same name, both imagery and title allude to the vulnerability of Black youth. While Roberts attributes the title of this series to a combination of Lauryn Hill and Mariah Carey’s albums The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill and The Emancipation of Mimi, respectively, one should also interpret it in relation to Carter G. Woodson’s historic text The Miseducation of the Negro, originally published in 1933.[7] Woodson, a teacher himself, wrote about the integral role that education has in perpetuating racialized insecurities and subjugation amongst Black American youth. In the introduction he writes that the “question which concerns us here is whether these ‘educated’ persons are actually equipped to face the ordeal before them or unconsciously contribute to their own undoing by perpetuating the regime of the oppressor.”[8] Woodson’s message stems from an understanding that children are shaped by societal ideals. He points out that the racism weaved into the structures of American civilization, including education, directly impacts the ways in which children see themselves. To be a Black girl in America means navigating, as a child, a system that has a history of upholding sexist and Eurocentric ideals that directly work against your treatment as an equal individual.

In a 2018 study, Kathryn Harper and Becky L. Choma highlighted the harmful effects of racialized beauty standards placed upon Black women and children in America.[9] As they explain, the danger arises from the “intrinsic entanglement” between one’s appearance and sense of worth, which can disproportionately lead women and girls to experience forms of self-hatred.[10] In his book White, Richard Dyer analyzes the dominance of representations of whiteness and asserts that Caucasian characteristics such as light skin and straight hair have become synonymous with beauty and high moral standards.[11] He explains that this standard of whiteness leads to colorism; the privilege given to those with lighter versus darker skin tones.[12] Emphasizing the vulnerability of children to these internalized ideals, Dyer also cites Marina Warner’s assertion that blondness and whiteness saturate Western fairy-tales and are subsequently associated with merit and beauty.[13] Despite Woodson’s warnings about operating under the systematic codes of the oppressor, Black Americans are often unknowingly influenced by the Eurocentric beauty ideals that populate the media they consume.

In her essay “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color,” Kimberle Crenshaw relates the devaluation of Black women to their characterization within cultural material and imagery.[14] In the current era of mass culture and image circulation, everyone is constantly bombarded by information that spreads and reinforces cultural values such as gender norms and beauty ideals. Roberts utilizes materials taken from mass communication sources such as magazines and advertisements in her depictions of children to demonstrate and undermine the influence these materials have over identity formation. Roberts deconstructs the presentation of images of women and children of color, and in doing so, she calls attention to the agency these materials have in informing the public’s valuation of them. By inserting images of white models taken from fashion magazines into these compositions, Roberts forces the viewer to consider the harm done to children who do not fit into the narrow scope of white aesthetic standards that are treated as norms of beauty and morality.

Through the collage format, Roberts resists singular conceptualizations of her depicted figures’ identities. In a conversation with Amy Sherald and Teka Selman, Roberts said “I feel like we have to, sometimes as [B]lack people, be chopped up so much just for people to accept and to digest us, instead of taking us as a whole individual.”[15] Instead of presenting the public with a unified image of an exemplary Black subject, Roberts uses her collages to reveal the “fractured nature” of how Black citizens are often understood.[16] By demonstrating the impossibility of encompassing a singular human identity through artistic depiction, she reminds the viewer of their own composite nature comprised of overlapping experiences. As Jacqueline Francis points out in relation to the collage works of Romare Bearden, the idea of a unified, universal character is considered by many to be a symptom of Western consciousness.[17] She emphasizes the idea that in popular culture, people find comfort in the ability to understand identity in a singular manner, as if it were an unchanging, stable entity.[18] Through the asymmetrical placement of facial features and body parts, Roberts unsettles the viewer and undermines their ability to make speedy conclusions about identity based on appearance.[19]

Miseducation of Mimi participates in this conversation through the layering of clashing and variously coded imagery. On the left side of the composition, we see a lounging figure sitting against a pattern of concentric black-and-white squares, the regularity of which emphasizes the figure’s asymmetry. The limbs and facial features are all taken from different color and grayscale sources, coming together to create a figure who, once again, resists immediate classification. The components that make up her face are youthful, but the wear on her visible foot suggests the effects of time and labor. Her ruffled apron evokes a history in which Black women were subjugated to domestic labor in American households. Behind the figure is an image of a white dress against a blue background which looks to be cut out of a vintage catalogue or dress pattern. On the lower right corner is a grayscale but clearly blonde-haired white woman, whose original legs have been replaced with a pair of long slender ones wearing black hose. The legs of the two figures stand out in relation to one another. The bare bent legs of the figure on the left are larger in scale than those of the standing figure on the right. Small distractions adorn the figure’s body, such as the green plastic grass evoking a crown; part of the artist’s strategy of resisting a clear-cut reading of the figure. The title of the work presents the idea that the child is being informed or educated by the image to her right. The ubiquity of Roberts’ material sources cut from paper magazines and culled from plastic packaging once again implies the vulnerability of children to the idea that aesthetic characteristics of white women are more beautiful or desirable than those of Black women, echoing the message of Woodson’s text.[20]

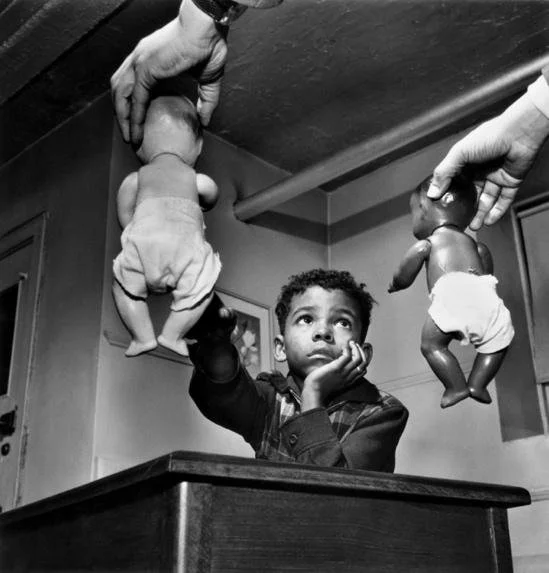

Figure 3: Gordon Parks, Untitled, Harlem, New York, 1947, gelatin silver print, image: 7 × 6 7/8 in. Courtesy of and © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Roberts’ use of photographs of children calls upon a history of photographic commentaries on childhood. Two examples of this can be found in the work of Gordon Parks and Helen Levitt, whose contrasting depictions of children underscore their vulnerability to societal racism as well as the power of their imagination to reconcile given circumstances. In Gordon Park’s 1947 photograph, Untitled [Harlem] (Fig. 3), we see a young boy emerging from behind a table or podium, presented with two baby dolls by a set of imposing white hands. Out of the two dolls (one Black, one white) the boy points toward the white doll while looking at the other with a worried, perhaps guilty, expression. The image appears to depict the “Doll Test,” a psychological study conducted in the 1940s by Kenneth Clark. As part of the study, children were asked which of the two dolls they preferred. The findings, which showed that roughly two thirds of Black children preferred white dolls, made it apparent that Black children saw the color of their skin as a basis for rejection.[21]

Figure 4: Helen Levitt, N.Y., c. 1940, silver gelatin print, 6 × 9 in. Courtesy of and © Film Documents LLC, courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne.

Alternatively, the works of photographer Helen Levitt foreground Black youth and the power of children’s imaginations. While most photographers who documented urban or working-class subjects during this period highlighted their poor living conditions, Levitt’s photographs of children at play emphasize their ability to transform their circumstances into environments of their own imaginative design.[22] In N.Y. (c. 1940) (Fig. 4), we find three boys, sitting, crouching, and lying on the steps of an East Harlem building. Two of them lean forward, peering off to the right side of the image, attempting to catch a glimpse of the enemy. The child sitting in the back timidly peers at his friend for protection as he stands with knees bent and toy-gun at the ready, poised to defend his territory (the stoop). The children in Levitt’s photograph transform their stark urban setting into a creative playground, displaying their ability to overcome assigned conditions and create spaces of wonder and enjoyment. In this way, Levitt shows that when given opportunities to exercise their imagination, children have the capacity to take possession of their circumstances by turning them into utopian spaces of youthful fantasy, if only for a fleeting moment. While Roberts’ photocollages call attention to problems and injustices Black children face, they also display her ability as an artist to manipulate and reinscribe their contexts. As Levitt’s works suggest, the conceptual space revealed by Roberts is a reinvention of Black figures that may allow children to imagine themselves as something outside the labels assigned by the dominant (white) culture.

Roberts’ use of collage brings the viewer’s attention to the contrived quality of her figures. Through the process of compiling images from a variety of sources, fragmenting, and then reassembling them, she not only resists Eurocentric expectations of singular identity, but also presents an intricate notion of Blackness that cannot be fully understood or controlled by the viewer. Roberts’ photocollages denounce the historic treatment of young Black women within mass media and culture while announcing their importance through representation within a fine art context. The subjects of these works are not comprised for our viewing pleasure. Rather, through their complicated figuration, the viewer’s eye is forced to move around the composition while each element is perceived in reference to one another. Roberts’ procedure of reinscription makes possible the reconceptualization of the ways we understand one another and encounter our sources of information, while the priority she gives to child subjects presents them as potent symbols of identity formation who deserve attention.

Endnotes

[1] In her book black feminism reimagined after intersectionality, Jennifer C. Nash discusses various conceptions and definitions of “intersectionality.” Despite her criticism of the definition presented by Kimberle Crenshaw, I found her essay “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color” useful in demonstrating the ways in which intersecting levels of racism and sexism contribute to inadequate considerations and efforts toward addressing the specific types of racism and sexism experienced by women and children of color. I introduce the term to emphasize another layer of oppression faced by Black children specifically. Kimberle Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review 43, no 6 (July 1991): 1252.

[2] In her book black feminism reimagined after intersectionality, Jennifer C. Nash discusses various conceptions and definitions of “intersectionality.” Despite her criticism of the definition presented by Kimberle Crenshaw, I found her essay “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color” useful in demonstrating the ways in which intersecting levels of racism and sexism contribute to inadequate considerations and efforts toward addressing the specific types of racism and sexism experienced by women and children of color. I introduce the term to emphasize another layer of oppression faced by Black children specifically. Kimberle Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review 43, no 6 (July 1991): 1252.

[3] Batye Saar and Arlene Raven. Betye Saar: Workers + Warriors: the Return of Aunt Jemima (New York: Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, 1998), 3.

[4] Caroline A. Brown, The Black Female Body in American Literature and Art (New York: Routledge, 2012), 3.

[5] Deborah Roberts and Valerie Cassel Oliver, “Conversations with Mimi,” in Deborah Roberts: The Evolution of Mimi, ed. Andrea Barnwell Brownlee (Atlanta: Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, 2019), 44.

[6] Andrea Barnwell Brownlee, “The Evolution of Deborah Roberts.” In Deborah Roberts:

The Evolution of Mimi, ed. Andrea Barnwell Brownlee (Atlanta: Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, 2019), 16.

[7] Roberts and Oliver 2019, 44. Multiple written sources have discussed the relationship between Lauryn Hill’s album and Carter G. Woodson’s text, including a recent article published by NPR: Namwali Serpell, “How 'The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill' Taught Me To Love Blackness,” NPR Music, July 7, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/07/07/1013351060/how-the-miseducation-of-lauryn-hill-taught-me-to-love-blackness.

[8] Carter G. Woodson, The Miseducation of the Negro (Hampton: U.B. & U.S. Communication Systems, 1994), xi.

[9] Harper and Choma also note that colorism disproportionately affects women over men. Kathryn Harper and Becky L. Choma, “Internalised White Ideal, Skin Tone Surveillance, and Hair Surveillance Predict Skin and Hair Dissatisfaction and Skin Bleaching among African American and Indian Women,” Sex Roles 80, no 11/12 (June 2019): 735.

[10] Harper and Choma 2019, 736-737.

[11] Richard Dyer. White: Twentieth Anniversary Edition (Florence: Taylor & Francis Group, 2017), 3

[12] Harper and Choma also note that colorism disproportionately affects women over men, Harper and Choma 2019, 735.

[13] Dyer 2017, 71.

[14] Crenshaw 1991, 1282.

[15] Deborah Roberts, Amy Sherald, and Teka Selman, “Now We Can Deal with the Nuances of Who We Are,” Southern Cultures 49, no. 2 (Summer 2020): 144.

[16] Roberts and Oliver 2019, 40.

[17] Jacqueline Francis, “Bearden’s Hands,” in Romare Bearden, American Modernist, ed. Ruth Fine and Jacqueline Francis (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011), 130.

[18] Francis 2011, 130.

[19] Asymmetry as a visual quality is referred to by Zora Neale Hurston in her essay “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” writing “Asymmetry is a definite feature of Negro art. I have no samples of true Negro painting unless we count the African shields, but the sculpture and carvings are full of this beauty and lack of symmetry.” Zora Neale Hurston, “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” in Zora Neale Hurston: Folklore, Memoirs, and Other Writings (New York: Library of America, 1995), 834.

[20] Woodson warns that Black citizens are socialized to look down upon characteristically Black qualities. For example, he writes “The educated Negro…is disinclined to take part in Negro business, because he has been taught in economics that Negroes cannot operate in this particular sphere.” Woodson 1991, xiv.

[21] New York Times News Service, "Racial Self-Image Study 'Disturbing': Doll Test Findings Same as in 1940s," Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1987, 10.

[22] Lauren Graves, “Inheritors of the Street Helen Levitt Photographs Children’s Chalk Drawings,” Buildings & Landscapes 28, no. 1 (Spring, 2021): 61

Bibliography

Brown, Caroline A. The Black Female Body in American Literature and Art. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Brownlee, Andrea Barnwell. “The Evolution of Deborah Roberts.” In Deborah Roberts: The Evolution of Mimi, edited by Andrea Barnwell Brownlee, 14-21. Atlanta: Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, 2019.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43. No 6 (July 1991): 1241-1299.

Dyer, Richard. White: Twentieth Anniversary Edition, Florence: Taylor & Francis Group, 2017.

Francis, Jacqueline. “Bearden’s Hands.” In Romare Bearden, American Modernist, edited by Ruth Fine and Jacqueline Francis, 121-142. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011.

Graves, Lauren. “Inheritors of the Street Helen Levitt Photographs Children’s Chalk Drawings.” Buildings & Landscapes 28, no. 1 (Spring, 2021): 58-83.

Harper, Kathryn and Becky L. Choma. “Internalised White Ideal, Skin Tone Surveillance, and Hair Surveillance Predict Skin and Hair Dissatisfaction and Skin Bleaching among African American and Indian Women.” Sex Roles 80, no. 11/12 (June 2019): 735-744.

Hurston, Zora Neale. “Characteristics of Negro Expression.” In Zora Neale Hurston: Folklore, Memoirs, and Other Writings, 830-846. New York: Library of America, 1995.

New York Times News Service. "Racial Self-Image Study 'Disturbing': Doll Test Findings Same as in 1940s." Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1987.

Roberts, Deborah, Amy Sherald, and Teka Selman. “Now We Can Deal with the Nuances of Who We Are.” Southern Cultures 49, no. 2 (Summer 2020): 134-149.

Roberts, Deborah and Valerie Cassel Oliver. “Conversations with Mimi.” In Deborah Roberts: The Evolution of Mimi, edited by Andrea Barnwell Brownlee, 38-45. Atlanta: Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, 2019.

Saar, Betye and Arlene Raven. Betye Saar: Workers + Warriors: the Return of Aunt Jemima. New York: Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, 1998.

Serpell, Namwali. “How 'The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill' Taught Me To Love Blackness.” NPR Music. July 7, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/07/07/1013351060/how-the-miseducation-of-lauryn-hill-taught-me-to-love-blackness.

Woodson, Carter G. The Miseducation of the Negro. Hampton: U.B. & U.S. Communication

Systems, 1994.