Peering Through the Hood: The Material/Visual Culture of the Second KKK

TW: This article features a discussion and images in relation to a topic which may make readers uncomfortable, angry, and/or anxious. Please continue at your own discretion. Due to the sensitive nature of the content, all images (online) have been included at the end of this essay.

By: Michael Jacobs

Citation: Jacobs, Michael. “Peering Through the Hood: The Material/Visual Culture of the Second KKK.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, December 3, 2022.

Abstract: This piece takes a new look at the second Ku Klux Klan by utilizing the lenses of material and visual culture. Previous scholars have addressed the Klan as a business, such as Charles Alexander, Nancy Maclean, and Kathleen Blee. However, their research did not focus primarily on the manufactured materials, literature, and regalia produced by the Klan. Using 20th -century material culture as a lens for analysis is critical in understanding how collective groups of people relate to one another through objects and shared ideologies. This piece argues that focusing on the visual and material culture produced by the Klan opens new insights into the second iteration of the KKK. Primarily, the piece examines manufactured cultural items such as catalogs, brochures, newspapers, photos, and propaganda produced by and for the Klan. The central aims are twofold: to explain the cultural importance of the visual and material cultural objects and to show how the Klan was able to use merchandising to fund its “Invisible Empire.”

Keywords: Klu Klux Klan, collective materials, propaganda, commercialization, material culture theory

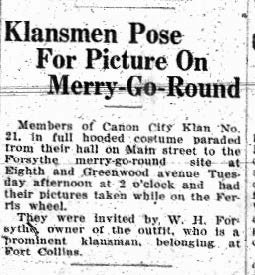

A headline in the Daily Record, a Colorado newspaper, stated, “Klansmen Pose for Picture On Merry-Go-Round.”[1] Today, this statement is an odd newspaper headline, but for Coloradans during the 1920s, this was one of many similar mentions of the Ku Klux Klan in local news. On April 7th, 1926, in Cañon City, a parade made its way down Main Street. The parade’s "unique" members were part of the Cañon City Klan No. 21. The parade was in response to Republican Candidate Oliver H. Shoup, former ex-governor of Colorado, running again in the 1926 gubernatorial election. Shoup did not support the Klan and if elected could interfere with the Klan’s operations in the state. To help bolster support for the Democrats, the Klan paraded down Main Street from their headquarters to the intersection of 8th and Greenwood, where a traveling carnival had been set up. William Forsythe, the carnival owner, and a member of the Klan had brought the carnival down south from Fort Collins.[2]

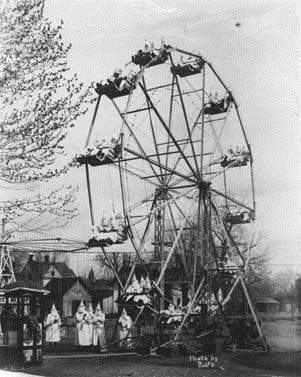

Also from Fort Collins was photographer Clinton Rolfe, who owned a photography studio called The Rolfe Studios.[3] He had recently moved to Cañon City and wanted to take photos of the event as a Klan sympathizer. At 2 o'clock in the afternoon, Rolfe staged the members of Klan No. 21 on and around at the Ferris Wheel.[4] Rolfe’s photo was never published in the Daily Record but was distributed to Klan members who posed in the picture. It wasn't until 1991, when a local family donated a collection of Klan-related photos to the Royal Gorge Museum & History Center, that anyone else laid eyes on this photo. The photo resurfaced in 2003 when the museum director, LaDonna Gunn, wrote an essay titled "The Protestant Kluxing' of Cañon City, Colorado."[5] After the essay had been uploaded to the museum's website, people began to share the photo, mainly through online forums. The photo took on a life of its own, being passed along to different websites, conveying the bizarre and forgotten history of the Klan's presence in Colorado and America in the 1920s. The reemergence of the photo in the digital space inspired a new academic interest in the history of the Klan. It personally was the inspiration for my research into the material and visual culture of the Klan.

These photos symbolize the dreams and aspirations of nationalist white Protestant ideology and are essential insight to understand the Klan’s individual and collective actions and the Klan’s intent and agenda in how they wanted the public to perceive them. This photo is one of many examples of multilayered pieces of visual and material culture produced by and for the Klan during the 1920s that was normalized in different parts of the country—photography was an avenue to reinforce their ideas among a wider swath of white Americans. In the past, the Klan was more accepted and tolerated among certain white and Christian demographics. This photo helped establish group identity for the readers of the newspaper who were supporters of the Klan, and most likely white Protestants. Historian Leora Auslander states that,

"both group identification and political consolidation and action are enabled by people's relation with things. Psychologists and sociologists have demonstrated how people ‘read’ style and gesture to recognize those who are like and unalike to identify and differentiate. These insights have important ramifications for historians striving to understand collective action."[6]

The Klan wanted to become part of the fabric of American culture, and they would achieve this by making Klan life inseparable from non-Klan life.

This article takes a new look at the second Ku Klux Klan, and how they took advantage of the modern and rising consumerism in America and used it for their own purposes. The Klan was able to create a brand-inspiring exclusivity and secrecy that would be enticing to a specific demographic of white, Christian Americans. The beginnings of the Klan’s second iteration are shrouded in mystery and merchandising. The second Ku Klux Klan differed from its predecessor in a few key elements. Firstly, the original Klan was founded by Nathan Bedford Forrest and a group of Ex-Confederates after the Civil War. Their experiences during the war and the following loss and occupation of their lands shaped them and made them look for people to blame for their misfortunes. Secondly, the Second Iteration of the Klan had a more ambitious organizational structure and political aspirations.

The second iteration of the Klan was founded on December 4, 1915, by a man named William Joseph Simmons, a large, red-haired former minister and fraternal organizer living outside Atlanta, Georgia. Simmons and thirty of his friends hiked up Stone Mountain one chilly night and burned a wooden cross at the top where they "practiced a weird ritual, and brought into existence the "Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, Incorporated."[7] In their petition they defined their new organization as a "patriotic, military, benevolent, ritualist, social and fraternal order."[8] The new Klan intended to be a business shrouded in the trappings of a fraternal order. Simmons' plan would be what differentiated this iteration of the Klan from its predecessor.

For Simmons, the new Klan was "designed to be quite respectable and harmless, Klansmen were to refrain from coercive activity except perhaps to ‘righten’ an occasional ‘uppity’ Negro… Simmons [also] realized the drawing power of secrecy, ritual, mystery, and exotic nomenclature."[9] Simmons planned on rebuilding the Klan "brand" by creating a corporate charter for the organization in Atlanta and by structuring it as a business.[10] This allowed it to operate similarly to other fraternal organizations and allowed him to charge initiation fees called "Klectokens." Simmons would charge members for purchasing robes and hoods, as well as mandatory Klan life insurance.[11]

What further distanced this iteration of the Klan from the original was Simmons' ambitions for designing his fraternal project as a money-making scheme.[12] Simmons took advantage of America's recent capitalist boom and industrial marketplace of the 1920s to funnel money into his new Klan. He hoped his financial endeavors would bring the Ku Klux Klan’s ideological ambitions to fruition. Simmons used some of this money for the hiring of two Atlanta-based publicity agents in 1920.[13] Simmons chose Edward Young Clarke and Elizabeth Tyler of the Southern Publicity Association for one simple reason: their deep involvement with the Klan itself. Edward not only owned the company but was also the Imperial Wizard pro tempore from 1915 to 1922.[14] The duo had the task of increasing membership and expanding the Klan’s agenda in the South and Southwest.[15] They instructed field organizers to “play upon whatever prejudices, anti-Catholicism, anti-Semitism, racism, or moral zealotry.”[16] Their instructions worked; sixteen months later, the Klan had reportedly gained over 90,000 new members and brought in over a million dollars from initiation fees and sales from regalia.[17] For Simmons, it appeared to be mostly about financial gain, but for his followers, it was about ideology.

Previous scholars have addressed the Klan as a business, such as Klan historians Charles Alexander, Nancy Maclean, and Kathleen Blee. Maclean and Blee expanded this research into the field of gender and women’s studies and women’s roles in the organization. However, their research did not focus on the Klan’s manufactured materials, literature, and regalia. Using 20th century material culture as a lens for analysis is critical in understanding how collective groups of people relate to one another through objects and shared ideologies. The Klan enticed the white population by making an homage to knights of the crusades who defended Christianity. Furthermore, the Klan tapped into perceived ideologies of the old South by elevating values such as chivalry and honor and exploiting the dark inner fears of those who felt like their role in society had been taken away.[18]

I argue that the Klan’s visual and material culture opens new insights into the insidious second iteration of the KKK. My methodology relies on an object-driven analysis that is used by material culture historians such as Kenneth Cohen, focusing on the produced materials as the main tool of analysis. I focus on the Klan’s manufactured cultural items created by and for the Klan, such as catalogs, brochures, newspapers, and photos, which could all be considered propaganda since a part of its purpose was to influence outside perception of the Klan. My central aims are twofold: to explain the cultural importance of the visual and material cultural objects and to show how the Klan was able to use merchandising to fund its “Invisible Empire.”

Photography

Photography was a powerful tool for the Klan to normalize their actions in the eyes of white Protestants and to instill fear into Catholics, Jews, African Americans, and anyone they deemed "enemies of America." The Klan understood the power of this relatively new technology and used it to their advantage to promote their organization and gain followers. By making visible its commonplace pastimes, the Klan hoped to show it was no different than other clubs, fraternal orders, and organizations in America. Showing themselves to the nation was a cultural project aimed at integrating Klansmen into mainstream American cultural life. The Ferris Wheel photo conveyed that the Klan and its presence were ubiquitous and irrefutable in the region. This photo also exemplifies the Klan’s cultural power between 1915 to 1930.[19]

When viewing Klan photos with our contemporary eye, it is crucial to understand the term "period eye." In her essay "Weaving the Way towards Liberty," art historian Elizabeth Hawley discusses the "period eye" concept coined by British art historian Michael Baxandall. The period eye highlights the importance of "attempting to interpret artwork in the way that its original audiences would have, rather than through the lens of our own contemporary experience."[20] What would audiences in the early twentieth century see in the images and cultural products created and disseminated by the Klan? How might those perceptions bolster the Klan’s claims to legitimacy?

When viewing photos of the Klan, contemporary viewers see something that underscores the acceptance and daily presence of the Klan in parts of American life. Historian Kenneth Cohen offers another important methodological insight when he discusses a “multidirectional” approach to material culture. In the article “Sport for Grown Children’: American Political Cartoons, 1790-1850,” Cohen quotes Archeologist James Deetz, who explains a multidirectional approach as "working back and forth between [artifacts] and a wider selection of documentary sources in order to broaden the interpretive conclusions of artefactual analysis."[21] This method of analysis helps us look through the lens of the period eye, and an investigation and analysis of these photos’ historical contexts can emerge. The Colorado Ferris Wheel photo conveys the tolerance for Klan members in daily life and their established place in broader society. Their ability to wear their costumes in broad daylight and pose for a photo reflects their encroachment into society at that point in time.

Fig. 5 depicts women of the WKKK (an auxiliary and sometimes separate entity of the KKK), posing for a photo while holding “Thanksgiving Baskets,” which contain food and other items they would hand out to needy families.[22] The WKKK members are not wearing full hoods that hide their faces. This is in clear contrast to male members of the KKK who wore full hoods when they posed for photographs. The reason for this contrast is discussed by sociologist Kathleen Blee in her book Women of the Klan, “Masks were clearly intended to disguise the identity of Klanswomen in public, but the WKKK insisted that masks had only a symbolic purpose.”[23] The members of the WKKK believed they were doing nothing wrong, and their organization was just like any other organization, such as the American Red Cross or the Salvation Army. When it came to charitable activities, they acted like any other benevolent society.

Lastly, Fig. 5 also demonstrates the new technique of an early type of photoshop. The baby pictured in the Lil ‘Klan hood is superimposed over the original image; this technique was also applied by the Klan when they would superimpose themselves onto important monuments or sites.[24] This photo is a prime example of propaganda and visual manipulation that the Klan was able to use to further their agenda. The act of merging American traditions with Klan regalia further blurred the line between Klan life and ordinary life. By printing these types of photos, the Klan wanted to secure their brand as a White, American, and charitable organization that was there to do good for the community.

In Colorado during the 1920s, the Klan saw great success and considered the state a stronghold for their organization. A reason for this success was that the majority white population in Colorado was Protestant. White Protestants during this time had fundamentalist religious views that included the infallibility of the Bible and the disavowal of the theory of evolution, which ran parallel to the Klan’s beliefs. The success of the Klan in Protestant areas stems from these shared beliefs regarding Catholics, temperance, and superiority. The Klan focused on achieving political power in the state through campaigning and supporting both Pro-Democratic party candidates and by threatening minorities. Because of this, the Klan had a massive influence on the state and local levels of Government. Governor Clarence Morley was a Klansman, and Senator Rice Means was Klan-endorsed. The mayor of Denver, Benjamin Stapleton, was a Klan sympathizer, and the Grand Dragon (Realm leader) of the Colorado Klan was Revered Fred Arnold, the Cañon City First Baptist Church minister. [25]

In Colorado, Klan membership numbers reached as high as 35,000 men and 11,000 women during the 1920s.[26] High membership was a result of the Klan’s heavy involvement in local politics, which helped push through Klan-oriented legislation.[27] Furthermore, like other candidates, Klan candidates' campaigns involved booster events, festivals, and sponsored gatherings. These sorts of pageantries were vital in getting votes and support.

“[A] myriad of Klan weddings, baby christenings, teenaged auxiliaries, family picnics, athletic contests, parades, spellings bees, beauty contests, rodeos, and circuses, it is perhaps little wonder that the 1920s Klan is recalled by former members as an ordinary, normal, taken-for-granted part of the life of the white Protestant majority. For members, the Klan defined the fabric of everyday life… in the minds of its members, the Klan become understood as little more than “just another club”[28]

Having all these activities under the white hood in public was not only a show of power and authority but further connected daily life and Klan life to make them inseparable. All this of course was a façade—a smoke screen meant to distract the population through bread & circuses. This was all an attempt to steer the focus away from the Klan’s own form of vigilante violence and threats toward those deemed enemies of the Klan, who were just minority groups attempting to live in peace. The blending of sacred moments in life with Klan pageantry further obscured the difference between the violence the Klan brought down on one hand and the seemingly normal “club” status seen by the white Christian population on the other hand.

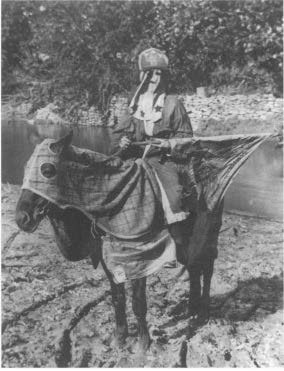

In Colorado, this interconnectedness took on many different, unique forms. On a summer afternoon in July of 1925 at the famous Overland Park racetrack in Denver, the Klan hosted a "Klan Day," which involved members racing in their white robes in white cars. The racecar in Fig. 6 was called the "Miller Special," and was owned by Ralph De Palma, a famous Italian race car driver who won the 1915 Indianapolis 500.[29] Driving the car was Mr. Miller, seen in the photo holding his cap and wearing a white duster. This photo is an example of historian Steven Conn’s interpretation of artifacts as "not only natural facts in themselves, but the evidence they contain can be read to establish historical facts…"[30] The existence of this photo in all its incongruity helps illustrate the strange normalcy that the Klan held in parts of white America.

Fig. 7 shows a ceremony held at South Table Mountain, an abandoned resort the Klan had taken over during the 1920s. It served as a location where ceremonies, cross burnings, and meetings were conducted. This meeting could have been an initiation ceremony because many who are not dressed are in the center surrounded by fully costumed members. Furthermore, a massive burning cross can be seen adjacent to an American flag, as well as a smaller electric cross.

Fig. 7 is another example of photos conveying the establishment of the Klan in this area so their presence would not go unseen. These photos can also be seen as a microcosm for the events unfolding around them, part of the Klan's formula to gain interest and support. The Klan’s goal with these ceremonies was to express a sense of power and authority by demonstrating that they could do these large gatherings without any interference. Secondly, by conducting these ceremonies they grew their numbers and ability to oppress and threaten marginal groups.

To gain supporters, the Klan organized public gatherings (as portrayed in Fig. 7) that involved "employing charismatic speakers to stoke the fires of interest in the organization, continually emphasizing its propensity for useful and patriotic public service. Almost always, these speakers were Protestant ministers brought in from areas where the Klan had already flourished."[31] These were not unusual spectacles: it was part of their playbook. Hosting these parades and events helped them integrate themselves into the local Protestant white communities. The popularity of Protestant iconography in American culture was a tactic the Klan implemented so they could appeal to a wider audience.

The Klan believed itself to be “Pro-American” and the upholder of Protestant values such as temperance, anti-Catholicism, and fundamentalism. This was constantly being addressed by respected leaders of the community who preached fiery speeches that reminded members of the organization’s true purpose and its function as a religious organization. Below is a section from one of those speeches.

"[This] was not a lodge, but an army of Protestant Americans. As a mass movement to secure the alleged birthright of Anglo-Saxon Americans, it could achieve that goal only through an aggressive application of the art of Klancraft. That would require winning the confidence of the community by recruiting respectable local men and making the Klan a civic asset."[32]

Speeches like these were used to get the crowd fired up and cement a sense of group identity and a mutual goal of securing their “birthright.” Within these speeches, the Klan utilized their own “slang.” In this case, it is the term “Klancraft,” which is referring to the book, Science and Art of KlanKraft. The book highlights the importance of “Klanishness” which can be broken up into six groupings: Domestic, Racial, Imperial, Patriotic, Moral, and Vocational. The book discusses how Klan ideology relates to all these different groups and how to act “Klanish” in each of these situations.[33]

The legacy of the KKK was cemented in photography. Analyzing these images is vital for understanding how the Klan became an integral part of Protestant culture and daily life for its members and those included in white society. The photos are reflections of society in the 1920s which saw a tightening of the ideas of manhood and religious morality. The Klan capitalized on this and expanded their power and influence. Using Colorado as an example of how influential the Klan was not only in the South but in other parts of the country, demonstrates that hatred and racism have no geographical boundary. The plethora of photos of the Klan, especially during the 1920s, is a shocking reminder that what was once seen as a typical and average photo is now viewed with shock, revulsion, and surprise. By looking through the lens of material and visual culture, historians can see the Klan’s impact on American culture through their use of photography, creating a sense of collective identity influenced by their racism and Christian nationalism.

Manufactured Products

The major reasons for the Klan’s success in the 1920’s were twofold. The Klan tapped into the anxieties of Protestants, other non-Catholic denominations of Christianity, and the white population by playing into long-standing fears about African Americans, Immigrants, Catholics, and Jews. The second reason for the Klan’s success was that they could promote “Americanism” by taking advantage of American capitalism and merchandising. This intervention in American capitalism made the Klan seem like other fraternal orders by producing their own regalia, literature, and material culture.

Analyzing the Klan’s products through a material culture lens helps answer how the Klan was successful in recruiting white men and women to their ranks. One of the most notorious and defining pieces of produced goods of the Ku Klux Klan was their robes and hoods. The regalia, and symbols used in the regalia, are reflections of a nationalist White Protestant society.[34] These pieces of visual and material culture intertwine Christian iconography, from burning crosses to their Latin banners, mottos, and symbols, reflecting their values as an organization.[35]The Klan decided on white regalia for a few reasons. Historically, the Klan used the color white to portray dead Confederates' ghosts to terrorize Black communities in the South.[36]Secondly, their costumes evoked their white male identities and ideas of "masculinity" and reflected their fitness to compete with "lesser races" in this brutal Darwinian ideology.[37] The design of the costumes themselves, worn by the first iteration of the Klan after the Civil War, was inspired by Mardi Gras and Carnival costumes in New Orleans. These are similar to what people still wear at the festivities today. The irony is that these celebrations are Catholic in origin and their costumes have been co-opted by a group that espouses anti-Catholic views.

The discussion about the origins of the robes and regalia is not well explored. One of the few historians exploring the robe’s origins is Elaine Frantz Parsons, a historian of violence, gender, and race in the 19th century. Parsons focuses on the first iteration of the Klan’s regalia in her article, Midnight Rangers: Costume and Performance in the Reconstruction Era Ku Klux Klan.[38] Her article is a prime example of a material culture methodology used to explore the Klan’s actions and origins. In a twist of irony, Parson explores how the robes worn by members of the Klan were influenced and inspired by African American and Caribbean culture:

Klansman’s construction of their costumes and performances within the carnivalesque tradition was itself a form of cultural miscegenation. Although carnival has early modern European roots, most scholars have maintained that carnival traditions in the southern United States were more immediately influenced by African American and Caribbean culture…One can see some striking examples of this cultural taking in Klan performance. Some Klansmen’s predilection for bull horns and animal skins, for homemade or unusual instruments or for disorderly pastiche design elements.[39]

This homemade style of attire died with the first iteration of the Klan. When Simmons resurrected it, Klansmen and women began to only wear the easily identifiable white robes. Another reason for white regalia was to symbolize purity and a connection to godliness and Christianity. Because the Klan believed itself to be a Protestant religious order, historians need to take seriously the Christian elements of its material culture.

The Klan did not separate the sacred and the profane, using both as tools in their quest to become part of mainstream society. The Klan's connection to Protestant churches ran deep, with many preachers and ministers being part of the Klan and even running certain Realms (territories). Rev. Booth, a Klan sympathizer and preacher in Michigan, “ was keen to praise KKK members as crusading Knights of Protestant Christianity. ‘The finest thing about the Klan to my notion,’ he said, in conclusion to his sermon, ‘is that the Bible is the basis for their constitution.’”[40] The connections between the Klan and Protestantism were profound, and the material and visual culture of the Klan reflects that. What made the second iteration of the Klan more popular and effective than the first, was that it was organized like a business and produced its own material and visual culture for profit. Simmons saw the Klan as a money-making machine and this mentality swelled Klan membership to over 2 million dues-paying members by May 1923. [41]

In one of the few articles that focuses on the second iteration of the Klan as a business, Kleagles and Cash: The Ku Klux Klan as a Business organization, 1915-1930, author Charles Alexander delves into how Simmons was able to make a massive profit off the Klan’s members. Alexander primarily examines Klan records and bank statements to illustrate how the Klan flourished financially. By 1923, the estimated net income of the national headquarters, “shrank to about $3,000,000, but the total income for all Klan organizational levels approximated $12,000,000.”[42] This accumulation of wealth came through multiple avenues. First, through initiation fees which started at $5.00.[43] Secondly, through an “Imperial Tax” which was placed on each member, usually around $1.80, and was collected yearly. Lastly and most importantly, through the sale of regalia and paraphernalia.

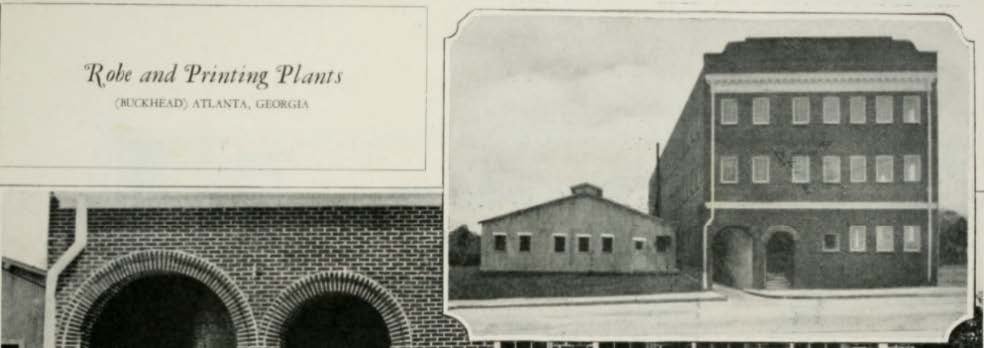

The manufacturing of Klan robes and regalia prior to 1922 was done by local garment factories that were present in the “Realms” but, as membership and their coffers grew, so did their needs. This expansion prompted the organization to look for a more permanent and in-house option to manufacture their regalia. With the help of an Atlanta Klansman, C.B. Davis, the Klan built their own factory outside of Atlanta called the Gates City Manufacturing Company.[44] At its peak production, the factory was producing 3,000 robes a week.[45] In addition to producing the robes and hoods, the factory had a printing plant that produced the Klan literature and catalogs.

Most of the workers at the factory were women, as seen in Fig. 9, which was not uncommon during the 20th century. However, the women in all white were not typical women, they were members of the WKKK. Not only did the Klan now have its own production facilities, but it also employed its own members to work there. The staging of the photo also suggests that the KKK wanted those who viewed the photo to know and appreciate their loyal and multifaceted manual labor force.

The internal production of Klan materials not only gave the Klan more power over their own products but made it much cheaper to produce, creating a higher profit margin. Before the establishment of the factory, the Klan had to pay $4.00 a piece for the robes and sold them for $6.50. Afterward, it only cost them $2.00 a piece to make but they still charged the same price, increasing their profits by $2.00 per robe.[46] Since the Klan had over 2 million active members who were required to purchase robes from them, this created a massive gain in revenue.

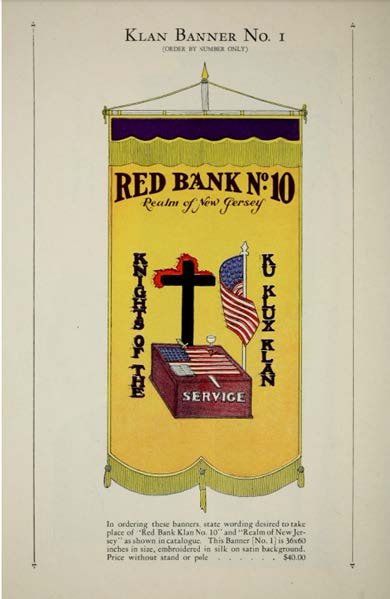

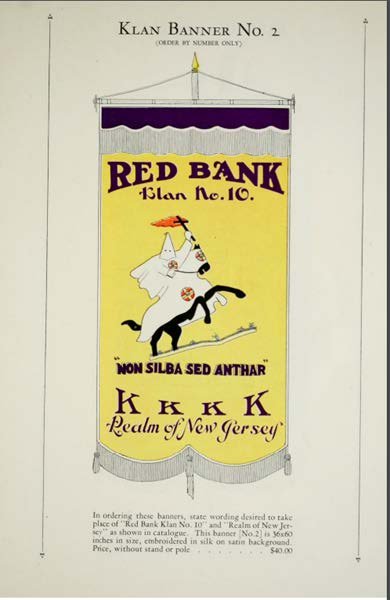

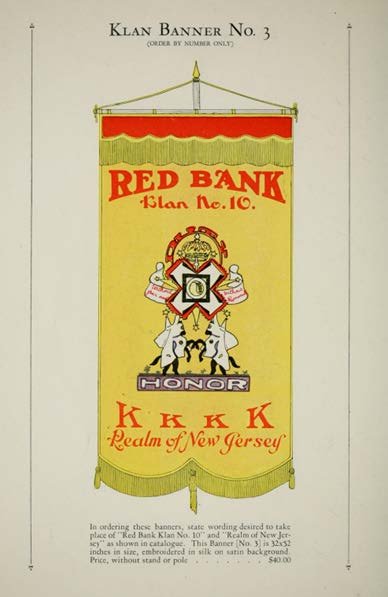

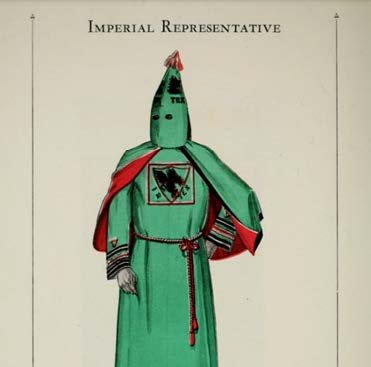

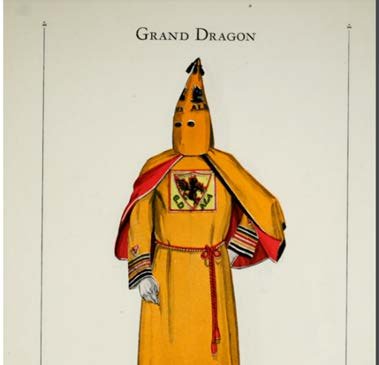

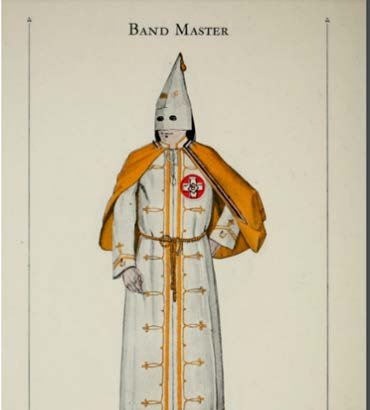

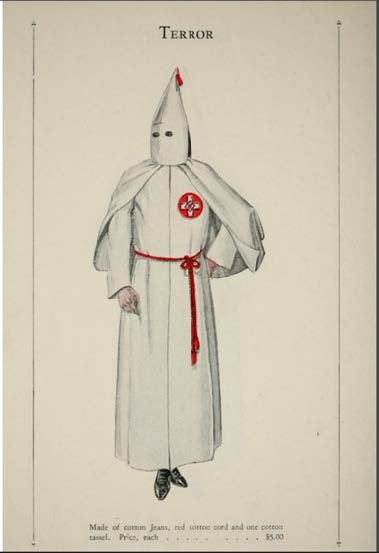

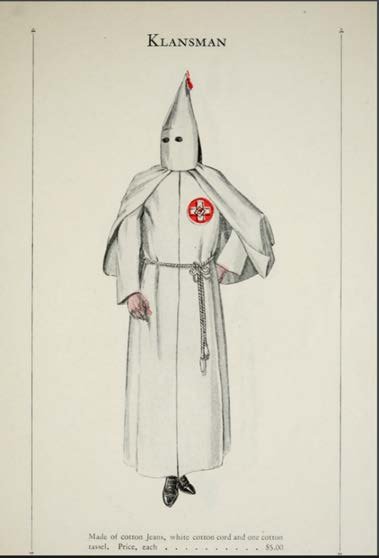

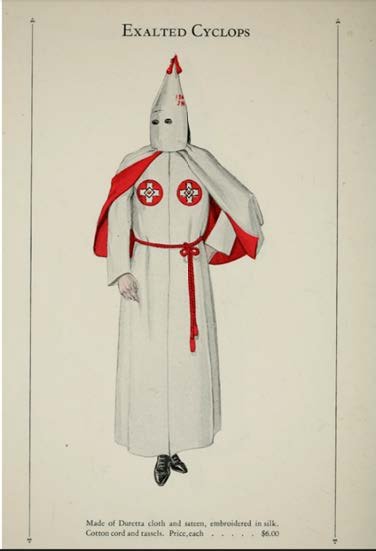

One of the rarest and most shocking pieces of material culture produced at the factory was the Catalogue of Official Robes and Banners. The catalog shows the materials used for robes, and most significantly depicts in color eighteen different styles of robes for various ranked members. This catalog conveys the hierarchy and organization that was put in place by the Klan as indicated by different colors. The use of a catalog helps the Klan seem similar to mainstream clothing manufacturers, such as Sears. The catalog also includes illustrations for different banners which were used to help promote the chapter at public events and meetings. Further, the catalog includes accessories that chapters should purchase such as a robe and hood travel case.

At the beginning of the catalog, there is a page that tells the reader how crucial and important it was for each Exalted Cyclops (chapter president) to keep the catalog “guarded and kept so it can be referred to at all times in ordering regalia, etc.”[47] This section also references the Klan’s new and modern factory, which they say, would theoretically help “local Klan’s at a worthwhile savings to them.”[48] This statement is false because the Klan still charged the same amount for robes though they were manufacturing them for less internally. This resulted in a larger profit for the organization itself, but with no true savings for its members.

Looking at Fig. 10, the banners illustrate a clear melding between the sacred and the profane. The blending of American, Protestant, and militant cultures is what makes these illustrations unique and historically significant. Seeing such illustrations in color gives them a real sense of immediacy, they show that these were real, and we see them existing in similar forms today. In the photos of the Klan, you usually do not get to see them in color, thus the bright and vibrant colors that are illustrated in the catalog are a surprise. This catalog brings these colors and costumes back to life. Each banner utilizes various symbols that are representative of the ideas and communities the Klan wanted to weave together and unite. The first banner on the left depicts the top of a podium with the American flag and a bible with a sword running underneath it; there is also an empty chalice on the top right. Behind the podium is a burning cross and an American flag waving. This banner is interweaving American patriotism, militarism, and the religious iconography of Protestantism into one visual moment.

The banner in the middle of Fig.10 has sloppy Latin and Gothic which states, “Non Silba Sed Anthar” which means “Not Self, But Others.”[49] These words are to inspire a sense of community and unity. The Klan used a debased version of Latin to make a connection to past crusaders who fought for Christianity, because the Klan believed they were on the same holy mission.[50] The third and final banner depicts the New Jersey chapter's emblem and location which is in Red Bank, New Jersey with the word “Honor” in the center. Honor is emphasized here because of their belief in the worthiness of their cause. Below each banner is a description of the size and material used. Each banner is exactly 32x52 inches and is embroidered in silk atop a satin background and costs $40, however, stands or poles to hang your banner were sold separately.[51]

The sample banners in the catalog all state they are for the “Realm” of New Jersey. Why would the Klan use New Jersey banners as the model in the catalog? This could be a coincidence. However, this may have been a calculated propaganda tactic geared towards the massive recruitment drive in the tristate area between New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania during this period. The Klan saw massive success in recruiting northerners from the Jersey Shore, more specifically Monmouth County. In that county alone, the Klan claimed to have over 7,000 members.[52] Using a New Jersey realm banner as a model could have been a conscious decision by the designers to convey the Klan’s influence in the North and across the nation.

The catalog allows for great insight into how the Klan dressed themselves and used dress performatively and symbolically. Though many only associate the Klan with their white robes, some lesser-known costumes/ranks came in many different colors, such as a spring green for Imperial Representatives and orange for Grand Dragons.[53] Analyzing these variations in color by rank is significant because it helps expand the knowledge about the Klan’s organizational structure and their ability to develop their own expansive regalia and use this regalia for many purposes. After extensive research, this 1925 catalog is one of a kind and no other similar catalog could be found from other years.[54] Finding this piece of rare material culture demonstrates that this iteration of the Klan was business-minded and made a clear effort to appear as just another fraternal organization.

When examining Fig. 11, which portrays two high-level members as well as a “Band Master,” we can see how each rank had its own color scheme denoting different materials: the higher the rank, the better the material. Fig. 12 gives us a sense of the common colors used for the rank-and-file Klansman. Their costumes were also cheaper than the higher-ranking members. Costumes in Fig. 12 were five to six dollars apiece while “GrandDragon” and “Imperial Representative “costumes were over fifty dollars per costume. Accounting for inflation, these high-ranking robes would cost over seven hundred dollars today. Furthermore, the higher-ranking Klansman robes were made of silk and satin adorned with military tassels. This use of tassels demonstrates how Klan members believed themselves to be in military order and wanted to portray this publicly. However, the regalia also had symbols and icons which were taken from Christian and American influences, such as crosses and eagles on the hoods.

We can analyze the regalia by employing McDannell's methodology concerning her discussion of religious objects which "frequently serve as the material reminders of significant events, people, moods, and activities by condensing and compressing memory."[55] These pieces of Klan material culture also evoke a nationalist Christianity that the Klan hoped to perpetuate and popularize. However, by emulating Christian heroes, such as chivalrous knights of yore, Klan members and designers showed a sense of childlike imagination and their transitory positioning between children and adults. Historian Kelly J. Baker elaborates in her book, Gospel According to the Klan: The KKK’s Appeal to Protestant America, 1915-1930. She addresses why these Protestant men fell into this fraternal folly,

“Fraternities allowed men to journey from the realm of childhood into the realm of manhood through ritual… these orders primarily served to instill masculinity and to transition young men into manhood…the second iteration of the Klan in the 1920’s embraced the fraternity as a realm in which men could reaffirm their religious faith and their patriotism in the face of an ever-changing world.”[56]

Being members of this fraternal order made these men and women feel safe. Having matching costumes that reinforced the Klan’s ideals and morals through symbolism gave them the power and authority to spread their influence across the nation, while also instilling fear in those who they deemed un-American and lesser than. By promoting a more masculine Christianity that needed safeguarding by chivalrous knights, the Klan gained followers who believed that they could be protectors of not only their families but the entire white race. Furthermore, Klan members enjoyed the invocation of Jesus since they too considered themselves martyrs. The Klan martyrs, like Jesus, “were symbols of Klan manhood that each member was supposed to emulate.”[57] The decision to dress in white robes with obvious Christian iconography was a visual representation and cue that Klan members were doing the lord's work in Jesus’s name.

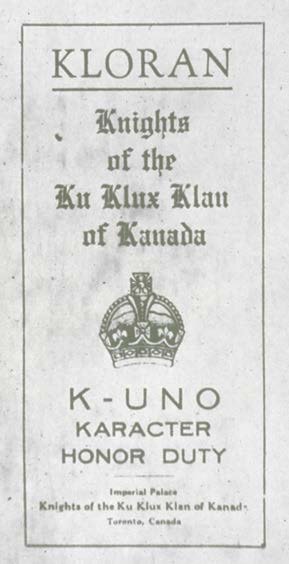

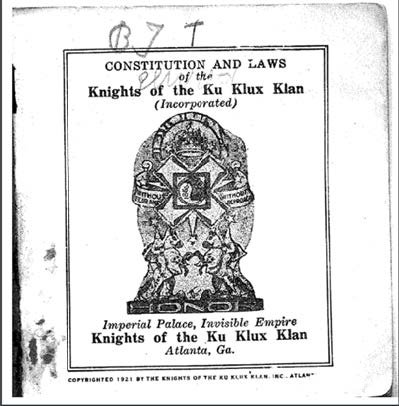

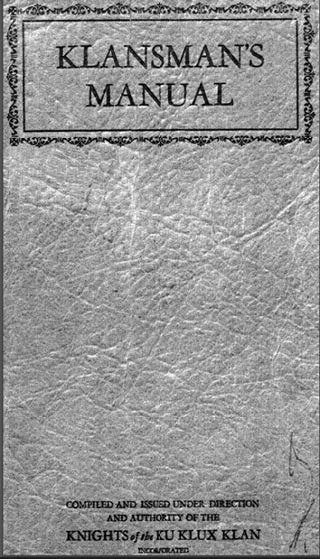

The Klan's ideology and the brand they were trying to establish can be comprehensively analyzed through three pieces of propaganda literature: the Kloran, the constitution and laws of the KKK, and the Klansman's Manual" Fig.13 depicts the “Kloran” which was the Klan’s bible. In the center is a constitution and laws for the KKK. Lastly, on the right is a Klansman’s Manual. Each member was required to purchase these books, which were all printed by the Klan, who pocketed the revenue. The manual is broken up into sixteen different sections with topics such as, “Order,” “Leadership,” “the Imperial Klonvokation,” and “Revenues.” To add to the mystery and mystique of the order they used their own makeshift “Latin.” They also “Klanafied” words, usually by adding a K.[58] The manual gives detailed insight into how to run a chapter, collect dues, and the expectations and requirements for each member.

Similar manuals are used in other fraternal orders, and they are crucial tools for new members to learn the values and rules held by their organization. This was no different for new Klansmen. A section titled “Alien World” discusses how members should interact with nonmembers and the outside world. They designated “all things and matters [that] do not exist within this order or are not authorized by or do not come under its jurisdiction shall be designated as the ‘Alien World.’ All persons who are not members of this order shall be designated as ‘Aliens.’”[59] The Klan was not the only fraternal order to have these types of designations for outsiders and they use this to their advantage. To defend their terminology, they mention that “College Greek Letter Fraternities apply the term “Barbarians” to those who are not members of their Fraternities, and Masonry uses the term “Profane” to designate non-Masonic persons and things.”[60] The Klan is constantly reaffirming that they are emulating other fraternal orders and are not unique in their “othering” of outside groups.

In addition to producing their own internal manuals and regalia, the Klan also published their own newspapers for more public consumption. Other fraternal orders had newsletters or bulletins, but the Klan expanded far past that. There were three large Klan-driven newspapers that were national, The Imperial Nighthawk, The Kourier, and The Fiery Cross. Each of these newspapers was used to perpetuate and highlight issues regarding Catholics, Jews, African Americans, and Immigrants through a Klan lens and perspective, such as portraying Catholics and Jews as un-American. African Americans were featured as ignorant and violent with immigrants being portrayed as corrupting Americas blood and values. These newspapers portrayed all these groups as despicable and enemies of the Klan and white Christian America.

The Klan used these newspapers to spread their messages nationwide and to reach a broader audience. Klan newspapers were just like other newspapers, they included articles, ads for businesses, and cartoons, but they always put the Klan in a positive light. For example, in The Fiery Cross it was common to see articles highlighting good works done by the Klan. This could take the form of building new churches, hospitals, and schools. In the April 6th, 1923, issue an article headline reads “KLAN BUILDS HOSPITAL FOR OIL WORKERS,” [61] this hospital would be for workers in El Dorado, Arkansas. The article goes into detail about how magnificent and modern the building will be and that this will be the “first and only hospital built, operated and controlled by the Ku Klux Klan.”[62] The Fiery Cross was the most prominent and widely read newspaper. It was first printed in 1922 and remained in print until 1925 with over 100 issues published.[63] The Fiery Cross office was in another stronghold for the Klan, Indianapolis, Indiana.[64] Just like Colorado, Indiana saw massive amounts of Klan activity and Klan success in local and state politics.[65]

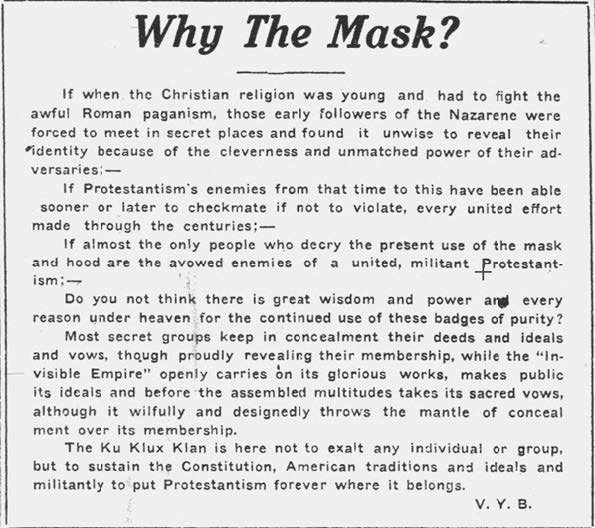

Like the other types of Klan propaganda, the newspapers were used as outlets to justify Klan activity and purposes. In their newspapers, the Klan was constantly reaffirming their ideals and justifying them through historic or religious rationales. Figure 14 is an article taken from the January 1923 issue of The Fiery Cross. Here the Klan is defending their reasons for wearing a mask through religious and historic contexts. Not only are the Klan justifying their concealment to the groups they prey upon but are also reassuring the white community of their purpose and connection to Christianity, comparing themselves to the “early followers of the Nazarene,” hiding from the “awful Roman paganism.”[66] Berating their audience with their propaganda these Newspapers also constantly questioned the relationship of the United States Government with Catholics and the Vatican. In another issue of The Fiery Cross from November 1924 they ran an article concerning Public Schools and what they called “American History as Taught by the Roman Catholic Church.”[67] The article stresses the concern for the indoctrination of American youth. The author, who is an Episcopal Minister writes that “not being able to turn back the hands of time and thus blot out the record of Romanism in America, they seek to rewrite its history.”[68] The author is referring to the loss of the Central Powers during WWI and the apparent weakening of the Vatican afterward. The Minister is making the assumption that the Vatican has influence over the American Public School system.

This fearmongering was part of the Klan’s agenda for keeping their audience in a state of unrest and under their influence. By controlling the narrative, they could influence their readers' thoughts and actions, which had direct and dire consequences for minorities and other religious groups. The manipulation of their message and image was abetted by their total control over their own manufacturing. This led to a consistency of ideological messaging and a fattening of their coffers. By tapping into American consumerism, they were able to make their message palatable to a wider audience.

Legacy

The legacy of the Klan lives on through its “brand” of hate and bigotry through manufactured goods, such as its white robes that are known within popular culture to represent the Klan. Even though The Klan is not in the daily headlines anymore their influence can still be felt and seen through the actions of other far-right groups, such as the Proud Boys (a Canadian-American Alt-right and neo-fascist violent political party that is exclusively male) that tend to take center stage. The Klan’s influence is widespread and insidious even today.

At the peak of Klan material production, there were hundreds of workers manufacturing Klan goods and propaganda; there is only one person now. This one person goes by the name “the Aryan outfitter,” but others call her by her real name, Mrs. Ruth. Mrs. Ruth is the last woman standing, she alone is manufacturing and producing the robes and regalia for the scattered chapters of the KKK throughout the country. In a rare 2008 interview for the magazine, Mother Jones, Mrs. Ruth was interviewed in her home/workshop.[69] Mrs. Ruth lives and takes care of her sick and dying daughter while taking orders for new robes,

While the Aryan outfitter might produce hate accouterment, she fosters good relationships with her customers, whom she describes as “good people” and “Christian.” She takes care of her daughter all day and all night, and, for the [interviewer], she was a nice lady who welcomed him into her home. In between sewing and her daughter’s care, Ms. Ruth explained to the [interviewer] the importance of the Klan historically as well as in the twenty-first century as a force of good and benevolence that protected, and still protects, the rights of white citizens.[70]

Mrs. Ruth believes herself and the Klan are still doing good work, and to her the legacy of the Klan is positive and members are good Christians. Mrs. Ruth demonstrates how material culture is still essential to the Klan more than a century after the Reconstruction Klan was founded.[71]

By manufacturing robes and regalia that pay homage to the Klans of the past she is making a conscious connection to the past and being an active participant in history. By combining the old ways of the Klan with a newer and broader white supremacy, splashed with neo-confederate iconography such as rebel flags, she is keeping the Klan alive. As seen in figure 15, this new style of robe includes the Army of Northern Virginia’s Battle flag, while also resurrecting the old triangle KKK symbol that represents three-letter Ks aligned in a triangle. Each robe is blessed by a kiss from Mrs. Ruth as well as a prayer, highlighting the continued significance of ritual Christian blessings in the Klan. Mrs. Ruth shows that, though diminished in some ways, the Klan still produces merchandise, regalia, and other miscellaneous objects and that Protestant Christianity remains a significant factor.[72] This expresses the deep-rooted connection between the Klan and Protestantism that has proven to be lasting. Furthermore, it conveys that while the Klan might be fading away, white Christian Nationalism is a consistent presence in this country.

Mrs. Ruth represents the order’s unique ability to reincarnate and reemerge in a variety of times and places in American history, as well as the audacity and permeance of the Klan’s vision of a white Protestant America.[73] Mrs. Ruth’s regalia and intertwined religious vision illuminate the Klan’s persistence to remain a part of the American nation. The orders may no longer be unified, “but their continued presence suggests the longevity of the Klan’s “brand”—religious nationalism and political rhetoric informed by intolerance and white supremacy—still applies.”[74] The Klan brand continues to live on and is constantly being adapted and used by other hate groups. To the new age of hate/nationalist groups, the Klan stands as a symbol of what they could be and is something they aspire to be.

Publishing this article in 2022, it is difficult not to make a connection between the events of last January 6th and its relationship to white supremacy. While there was no clear evidence of the Klan being present or seen in any large numbers, newer groups stepped into their place. Emboldened by the Presidency of Donald Trump from 2016 to 2020, white supremacy has a new face. Along with other white supremacy and militant groups, the Proud Boys were up front and showed the nation that white supremacy remains a major threat to this country.[75] Even a hundred years later, the Klan’s message of white supremacy, American militarism, and Evangelical Christianity is still with us. They might not be in the white robes and hoods like in the past, but they still fuel hate through consumerism in new mediums like social media, meme culture, and the internet.[76]

These new-age hate groups utilize the internet and social media for their benefit; through a large online presence, they reach potential members at a distance, something the Klan could have only dreamed of. What makes the Proud Boys unique is their ability to gain large amounts of younger Christian white males into their ranks. By using memes such as “Pepe the Frog” and pilfering military hand signals for their own organization, the Proud boys are creating their own “brand” of Express brand black polo shirts, flags, patches, and those catchy memes. The Proud Boys have been able to tap into modern-day American consumerism just like the Klan and use it for their own cause but take it a step further by utilizing social media.

The parallels between the KKK of the 1920s and the white supremacist groups of the 2020s are unmistakable. From finding the exact slogans used by the KKK in the 1920s on posters made by the Proud Boys and pro-MAGA groups to reliance on the same Christian iconography, both groups tap into American consumerism to fuel their hate-filled messages and missions. It is important that we study and understand the messages and material culture of the KKK so we can understand and resist the messages of today’s white supremacist groups.

Endnotes

[1]“Klansmen Pose for Picture on Merry-Go-Round,” Daily Record, April 27, 1926.

[2] Meg Dunn, “When the Klan Came to Colorado Part 2- Rise to Power,” last modified October 24, 2018, https://www.northerncoloradohistory.com/when-the-klan-came-to-colorado_rise-to-power/ .

[3]“Klansmen Pose for Picture on Merry-Go-Round,” Daily Record, April 27, 1926.

[4] “Klansmen Pose for Picture on Merry-Go-Round,” Daily Record, April 27, 1926.

[5] LaDonna Gunn, "The Protestant Kluxing' of Cañon City, Colorado,” Royal Gorge Regional Museum & History Center, https://rgmhc.pastperfectonline.com/ .

[6] Leora Auslander, “Beyond Words,” American Historical Review, (2005): 1022.

[7] Charles C. Alexander, “The Ku Klux Klan as a Business Organization, 1915-1930,” The Business History Review, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Autumn, 1965): 349.

[8]Alexander 1965, 349.

[9]Alexander 1965, 350.

[10] Alexander 1965, 350.

[11] Simmons was focused on creating the brand and using diction as a tool to help create a Klan language, which would add to the mystery. Some examples of these Klan terms are “kleagles” which are women Klan recruiters, “Klabee” which means treasurer, “Klaliff” is the vice president, a “Klarogo” is an inner guard of the local chapter, a “klavern” is an indoor meeting hall, a “Kloran” is the Klan’s ritual book and lastly, a “Realm” refers to a subdivision of the Invisible Empire equivalent to a state.

[12] Charles C. Alexander, “The Ku Klux Klan as a Business Organization, 1915-1930,” The Business History Review, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Autumn, 1965): 350.

[13] Livia Gershon, “The Ku Klux Klan Used to Be Big Business,” last modified March 7, 2016, https://daily.jstor.org/the-kkk-as-big-business/

[14] Charles C. Alexander, “The Ku Klux Klan as a Business Organization, 1915-1930,” The Business History Review, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Autumn, 1965).

[15] Livia Gershon, “The Ku Klux Klan Used to Be Big Business,” last modified March 7, 2016, https://daily.jstor.org/the-kkk-as-big-business/

[16] Alexander 1965.

[17] Alexander 1965.

[18] Historian Leora Auslander explores the study of material culture as it concerns group identity and society. In her scholarly work Beyond Words, she states that, "The use of material culture for the writing of history entails, therefore, the use of both theoretical or conceptual work that addresses the relation between people and things in the abstract, and that which focuses on those relations under particular forms of economy and polity. It also requires careful reflection on the relation of texts and things, how people have represented their object worlds in writing or used textual invocations of objects.”

[19] Enslaved African Americans and Freedman used photography as a connection to the past and as evidence of the horrors of slavery, as well as their successes as free men and woman. Deborah Willis discusses this in her book, Envisioning Emancipation where she states that, “scholars and theorists of photography have discussed the medium’s power to elicit and shape viewers’ emotional responses evoking milestones from birth to death. Photographs of enslaved and free black people allow us to contemplate not only the history of slavery and emancipation but also our continued ties to that history and legacies.” African Americans used photography to regain agency over their own lives and stories.

[20] Elizabeth S. Hawley,” Weaving the Way towards Liberty,” in Crafting Dissent, ed. Hinda Mandell (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), 33.

[21] Kenneth Cohen, “Sport for Grown Children’: American Political Cartoons, 1790-1850,” The International Journal of the History of Sport, no.28(2011): 1303.

[22] It should be clear that these specific families were usually members of the organization itself or those who fit into the Klan’s deserving list.

[23] Kathleen Blee, Women of the Klan (London: University of California Press, 2009), 36.

[24] “Kastle Kountry Klub,Photomontage of Klan member on South Table Mountain, Colorado, 1924.” Denver Public Library Digital Collections, 2021, https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll22/id/64785/rec/121

[25] Robert Alan Goldberg, Hooded Empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Colorado (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1981),134.

[26] Betty Jo Brenner, “The Colorado Women of the Ku Klux Klan,” in Denver Inside and Out (Colorado: University of Colorado; Colorado Historical Society, 2011), 60.

[27] Nancy Maclean, Behind the Mask of Chivalry (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 18.

[28] Kathleen Blee, “Evidence, Empathy, and Ethics: Lessons from Oral Histories of the Klan,” in The Journal of American History 80, no.2 (1993): 596-606.

[29] “Klan member at Klan Day at the races at Overland Park” Denver Public Library Digital Collections. Denver Public Library. July, 9 2021. https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll22/id/18418/rec/28

[30] Steven Conn, “Words or things in American History?” The Oxford Handbook of History and Material Culture, (2020):11.

[31] Craig Fox, Everyday Klansfolk (Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 2011), 5.

[32] Nancy Maclean, Behind the Mask of Chivalry (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 11.

[33] The term “klancraft” is referenced here as well and in other Klan literature. This in relation to their idea of practicing Klanishness and is discussed in a piece of literature produced by the Klan titled, Science and Art of KlanKraft. This manual included six types of “klanishness,” Domestic, Racial, Imperial and Patriotic, Moral and Vocational.

[34] Kenneth Cohen, “Sport for Grown Children’: American Political Cartoons, 1790-1850,” The International Journal of the History of Sport, no.28(2011): 1303.

[35] Elaine Frantz Parsons, “Costume and Performance in the Reconstruction-Era Ku Klux Klan,” The Journal of American History, no. 3 (2005): 830.

[36] Parsons 2005, 830.

[37] Parsons 2005, 830.

[38] Parsons 2005.

[39] Parsons 2005, 832-833.

[40] Fox 2011, 162.

[41] Charles C. Alexander, “The Ku Klux Klan as a Business Organization, 1915-1930,” The Business History Review, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Autumn, 1965): 359

[42] Alexander 1965, 359.

[43] Alexander 1965, 359.

[44] Alexander 1965, 354.

[45] Kelly J. Baker, Gospel According to the Klan (Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2011), 249.

[46] Alexander 1965, 355.

[47] Alexander 1965, 355.

[48]“Catalogue of Official Robes and Banners of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan”, Pamphlet Collection, Duke University Library. https://archive.org/details/catalogueofoffic00kukl/page/n1/mode/2up.

[49] Catalogue of Official Robes and Banners of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan”, Pamphlet Collection, Duke University Library. https://archive.org/details/catalogueofoffic00kukl/page/n1/mode/2up.

[50]Baker 2011, 100.

[51] “Catalogue of Official Robes and Banners of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan”, Pamphlet Collection, Duke University Library. https://archive.org/details/catalogueofoffic00kukl/page/n1/mode/2up

[52] The George Moss Collection At Monmouth University: Difficult History, Monmouth University Guggenheim Memorial Library. https://guides.monmouth.edu/c.php?g=827028&p=5937798

[53] “Catalogue of Official Robes and Banners of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan”, Pamphlet Collection, Duke University Library. https://archive.org/details/catalogueofoffic00kukl/page/n1/mode/2up

[54] I was able to find reference to a WKK catalog from 1923, however I was unable to find the actual catalog minus some very grainy photocopies.

[55] Colleen McDannell, Material Christianity: religion and popular culture in America (Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1995).

[56] Baker 2011, 100.

[57] Baker 2011, 102.

[58] One of the best sources in viewing the Klan vocabulary is the Klan constitution that breaks down the positions, and terminology used by the Klan.

[59] “Catalogue of Official Robes and Banners of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan”, Pamphlet Collection, Duke University Library. https://archive.org/details/catalogueofoffic00kukl/page/n1/mode/2up

[60] Catalogue of Official Robes and Banners of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan”, Pamphlet Collection, Duke University Library. https://archive.org/details/catalogueofoffic00kukl/page/n1/mode/2up

[61] “Fiery Cross-Hoosier State Chronicles,” Hoosier State Chronicles: Indiana’s Digital Historic Newspaper Program. Hoosier State Chronicles, 8/7/2022. https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=FC19230406&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------

[62] “Fiery Cross-Hoosier State Chronicles,” Hoosier State Chronicles: Indiana’s Digital Historic Newspaper Program. Hoosier State Chronicles, 8/7/2022. https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=FC19230406&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------

[63] “Fiery Cross-Hoosier State Chronicles,” Hoosier State Chronicles: Indiana’s Digital Historic Newspaper Program. Hoosier State Chronicles, 8/3/2021. https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=cl&cl=CL2.1923.01&sp=FC&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------

[64]Alexander 1965, 366.

[65] Alexander 1965, 366.

[66] “Fiery Cross-Hoosier State Chronicles,” Hoosier State Chronicles: Indiana’s Digital Historic Newspaper Program. Hoosier State Chronicles, 8/3/2022.

[67] “Fiery Cross-Hoosier State Chronicles,” Hoosier State Chronicles: Indiana’s Digital Historic Newspaper Program. Hoosier State Chronicles, 8/7/2022. https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=FC19241107&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------

[68] “Fiery Cross-Hoosier State Chronicles,” Hoosier State Chronicles: Indiana’s Digital Historic Newspaper Program. Hoosier State Chronicles, 8/7/2022. https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=FC19241107&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------

[69] Anthony Karen. “Aryan Outfitters.” Mother Jones, 2008. https://www.motherjones.com/media/2008/03/aryan-outfitters-kkk-seamstress/

[70] Baker 2011, 247.

[71] Baker 2011, 248.

[72] Baker 2011, 248.

[73] Baker 2011, 249.

[74] Baker 2011, 249.

[75] Both the Klan and modern Alt-Right groups share a similar ideology concerning the replacement or dilution of white society by immigrants and non-whites. In modern terminology this is referred to as the “Great Replacement” theory. The echoes of Klan ideology are heard in the chants of “Jews will not replace us” at the Unite The Right rally in Charlottesville, VA in 2017.

[76] Bulen Kenes, “The Proud Boys: Chauvinist poster child of far-right extremism, European Center for Populism Studies, 2021, 8. https://www.populismstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ECPS-Organisation-Profile-Series-1.pdf

Bibliography

Alexander C., Charles. “The Ku Klux Klan as a Business Organization, 1915-1930.” The Business History Review, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Autumn, 1965): 349.

Auslander, Leora. “Beyond Words.” American Historical Review, (2005): 1022.

Baker, Kelly. Gospel According to the Klan (Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2011), 249.

Blee, Kathleen. “Evidence, Empathy, and Ethics: Lessons from Oral Histories of the Klan,” in The Journal of American History 80, no.2 (1993): 596-606.

Blee, Kathleen. Women of the Klan (London: University of California Press, 2009), 36.

Brenner, Betty Jo. “The Colorado Women of the Ku Klux Klan.” in Denver Inside and Out (Colorado: University of Colorado; Colorado Historical Society, 2011), 60.

“Catalogue of Offical Robes and Banners of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan”, Pamplet Collection, Duke University Library. https://archive.org/details/catalogueofoffic00kukl/page/n1/mode/2up.

Cohen, Kenneth. “Sport for Grown Children’: American Political Cartoons, 1790-1850,” The International Journal of the History of Sport, no.28(2011): 1303.

Conn, Steven. “Words or things in American History?” The Oxford Handbook of History and Material Culture, (2020): 11.

Dunn, Meg. “When the Klan Came to Colorado Part 2- Rise to Power.” last modified October 24, 2018. https://www.northerncoloradohistory.com/when-the-klan-came-to-colorado_rise-to-power/.

Fox, Craig. Everyday Klansfolk (Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 2011), 5.

Goldberg, Robert Alan. Hooded Empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Colorado (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1981), 134.

Gunn, LaDonna. "The Protestant Kluxing' of Cañon City, Colorado.” Royal Gorge Regional Museum & History Center. https://rgmhc.pastperfectonline.com/.

Hawley, Elizabeth. ”Weaving the Way towards Liberty.” in Crafting Dissent, ed. Hinda Mandell (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), 33.

“Klansmen Pose For Picture on Merry-Go Round.” Daily Record. Tuesday 27,1926.

Maclean, Nancy. Behind the Mask of Chivalry (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 18.

McDannell, Colleen. Material Christianity: religion and popular culture in America (Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1995), 4.

Parsons, Elaine Frantz. “Costume and Performance in the Reconstruction-Era Ku Klux Klan.” The Journal of American History, no. 3 (2005): 830.

Willis, Deborah. Envisioning Emancipation (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press, 2013), 24.