The Science of Light in the Spiritualist Works of Evelyn De Morgan

Emily Snow

Citation: Snow, Emily. “The Science of Light in the Spiritual Works of Evelyn De Morgan.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, October 14, 2022.

Abstract: Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919) was an English painter and, behind closed doors, a practiced spirit medium. Her paintings have historically been characterized by a unique amalgamation of her association with the Pre-Raphaelites, her time in Great Britain and Italy, and her involvement in Victorian-era Spiritualism, a movement that became fairly mainstream in her lifetime. De Morgan was especially fascinated by the ascent of the soul beyond the physical world and increasingly explored this subject in her later works.

From about 1900 until her death in 1919, De Morgan’s paintings demonstrate the height of her desire to reconcile the material and the mystical realms. To visually express her personal theology as it evolved, De Morgan gravitated towards the concept of light both spiritually and scientifically. De Morgan likely gleaned concepts and imagery from 19th-century science publications on light, including well-known writings on prismatic refraction and chromo-mentalism, to formulate and legitimize the unique Spiritualist iconography present in her later works. This article discusses how she might have viewed and utilized scientific principles in tandem with contemporary spiritualist discourse, including an anonymously published compilation of her own automatic writing transcripts, aptly titled The Result of an Experiment.

Much like a glass prism can be used to expand the scope of the visible world, the act of studying and painting light was how Evelyn De Morgan attempted to materialize the mystical and bridge the gap between science and Spiritualism.

Keywords: spiritualism, light symbolism, prismatic refraction, chromo-mentalism, Evelyn De Morgan

The practice of Spiritualism, which originated in the United States, took Industrial Revolution-era Britain by storm in the mid-1800s. Spiritualism was predicated on the belief that a spirit realm exists and that people on earth could interact with it. Meanwhile, a growing mainstream interest in the scientific method encouraged Spiritualists to consider their sensory observations to be empirical evidence of the spirit world, highlighting a fascinating connection between the material and the mystical realms.[i] It was within this cultural context that the English painter Evelyn De Morgan was born Mary Evelyn Pickering into an upper-class family in London.

As a painter, De Morgan spent most of her life artistically exploring and evolving her own secular and spiritual ideas. This impulse was instilled in her from a young age, beginning with her cross-disciplinary childhood education, which was rare for girls to receive at the time. De Morgan was later accepted as a student at the Slade School of Art, which, in addition to artistic skill, required its pupils to demonstrate knowledge of the humanities and sciences. This prerequisite indicates that she would have been aware of and interested in contemporary scientific discourse.[ii] De Morgan also developed her artistic skills in the company of second-generation Pre-Raphaelites and Aesthetic Movement proponents—including family friends Edward Burne-Jones and George Frederic Watts and her uncle John Roddam Spencer Stanhope. By young adulthood, De Morgan had studied in London, traveled to Florence, and was successfully exhibiting and selling her early allegorical paintings.

Evelyn’s unconventional marriage to William De Morgan, a socially progressive writer, ceramicist, and Spiritualist sixteen years her senior, is what catalyzed her interest in Spiritualism. As a commercially successful artist and burgeoning Spiritualist in Victorian-era Britain, it follows that De Morgan would have gleaned concepts and imagery from contemporary discourse to develop the rich symbology that is unique to her work. As De Morgan’s artistic and spiritual ideologies matured in tandem, she increasingly fixated upon the symbol of light, which became a key component of her personal iconography. While developing her unique light-related symbology, De Morgan naturally would have looked to every available resource for inspiration—not just spiritual, but scientific. Advancements in light-related technology during De Morgan’s lifetime, including the invention of the electric lightbulb in 1879, captivated public interest and dramatically changed aspects of everyday life. The resulting popularity of prism lighting around the turn of the century, and ongoing scientific studies on the visible spectrum of light and color, also contributed to this widespread fascination.

Indeed, these were popular topics of discussion and intrigue among educated Victorians like De Morgan and her social circle. As such, she likely would have become familiar with Edwin D. Babbitt’s The Principles of Light and Color, a well-known volume of research on the visible spectrum of light. In August 1878, the same year that this book was published in the United States, a popular London newspaper—The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art—included a substantial review of the book in its “American Literature” section, demonstrating that, albeit an American publication, Principles of Light and Color was present in mainstream Victorian discourse.[iii] Looking to the latest scientific topics of her day, particularly those related to light, would have helped De Morgan legitimize and more fully formulate her use of light as a symbol in her Spiritualist works.

In Victorian culture, the boundaries between science and the supernatural were blurred. De Morgan would have viewed scientific discourse in tandem with, not in opposition to, Spiritualist discourse. From Matter to Spirit: The Result of Ten Years’ Experience in Spirit Manifestations by Sophia De Morgan, Evelyn’s mother-in-law, was widely read by Victorian Spiritualists. Sophia De Morgan’s From Matter to Spirit asserts an empirical approach to its research and utilizes language coded in scientific discourse. Evelyn De Morgan’s sister and biographer Wilhelmina Stirling noted the profound influence of Sophia and her husband Augustus on both Evelyn and William. She referred to Augustus, who penned the book’s preface, as “the first man of science in modern times who regarded and studied the phenomena of spiritualism…with seriousness.”[iv] De Morgan’s own understanding of the scientific and spiritual properties of light, and how she expressed it through her art, indicates a similarly empirical approach.

Like her mother-in-law, Evelyn De Morgan also became a practiced spirit medium. Privately, she and William conducted automatic writing sessions in their home over the course of several years. These sessions would have gone like this: the first person, usually Evelyn, would hold a writing utensil and the second person, usually William, would place his hand on her wrist. Then, entering a trancelike state, their hands would begin to move across the paper, with both participants believing they are being pulled involuntarily. The resulting communications were interpreted as messages from the spirit world. For the De Morgans, many of these transcripts came from spirits who described their view of the spirit world and the progress of their own spiritual evolution. In 1909, the De Morgans anonymously published a book of transcripts from their years of automatic writing sessions, entitled The Result of an Experiment.[v] The act of publishing these writings under this title indicates that they believed them to be both scientifically legitimate and spiritually significant.

After De Morgan's death, an admirer marveled at “the existence of a thousand secrets that will never be known” in her work.[vi] Indeed, De Morgan’s paintings are full of symbology that is unique to her. But what lacks adequate consideration is De Morgan’s dual engagement with Victorian science and Spiritualism. In fact, from about 1900 until her death in 1919, De Morgan’s paintings demonstrate the height of her desire to reconcile the material and the mystical realms. To visually express her personal theology as it evolved, De Morgan gravitated towards the concept of light both spiritually and scientifically. She likely gleaned concepts and imagery from 19th-century science publications on light, including well-known writings on prismatic refraction and chromo-mentalism, to formulate and legitimize the unique Spiritualist iconography present in her later works.

To help illuminate Evelyn De Morgan’s unique light symbology, this article discusses two main themes in the artist’s later works: one, the relationship between prismatic refraction and De Morgan’s visualization of spiritual evolution; and two: the relationship between chromo-mentalism and her visualization of spiritual auras. This article examines how De Morgan likely used concepts and imagery from nineteenth-century scientific discourse to formulate and legitimize her symbolic use of light in her late-career Spiritualist paintings, and her personal theological exploration of the material and the mystical.

The Rainbow Bridge: Prismatic Refraction and the Visible Spectrum

The use of a prism to observe the rainbow spectrum of refracted white light was key to scientific advances in the understanding of light. The process of using a crystalline tool to alter the scope of the visual world was also being applied to spiritualist experiments. Sophia De Morgan described the process of crystal-seeing in From Matter to Spirit: “Having placed the glass on the table, covering it so closely as to shut out from it and from [the spirit medium’s] eyes every vestige of light…she sat down in perfect quietness gazing on the glass.”[vii]

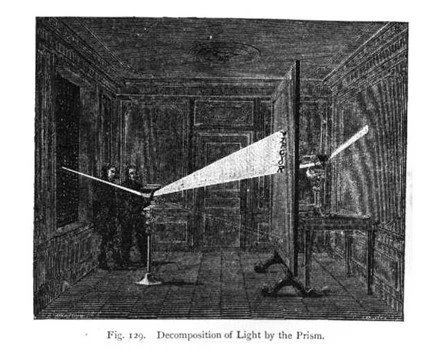

Figure 1: Decomposition of Light by the Prism, Edwin D. Babbitt (1878)

The process of prismatic refraction was explained very similarly by Babbitt in The Principles of Light and Color (Fig. 1). He wrote: “When sunlight passes through a slit leading into a darkened room, and then through a triangular piece of glass called a prism…the rays of light are separated by refraction into their constituent colors on the same plane as the rainbow and fall in an oblong figure on the opposite wall.”[viii] The fact that crystal-seeing and prismatic refraction required similar tools, conditions, and actions did not go unnoticed by Spiritualists. Sophia De Morgan made this connection in From Matter to Spirit:

“As an explanation of crystal-seeing, a spiritual drawing was once made representing a spirit directing on the crystal a stream of influence, the rays of which seemed to be refracted, and then to converge again on the side of the glass sphere before they met the eye of the seer. An enquirer, better acquainted than myself with polarization, refraction, &c., of light, would perhaps have been able to trace the analogy between the laws of external or natural, and those of internal or spiritual vision.”[ix]

Evelyn De Morgan’s painting titled The Kingdom of Heaven Suffereth Violence, and the Violent Take it By Force (Fig. 2) depicts an allegory of the soul’s journey from spiritual darkness to enlightenment. This journey is represented by the same female figure, possibly a self-portrait, repeated ten times in various states and colors. The Kingdom of Heaven embodies the successive phases of a soul “growing up into the light”—a phrase De Morgan used in The Result of an Experiment to describe spiritual growth.[x] The refraction of light into a rainbow spectrum provides a compelling symbol for the soul’s gradual spiritual enlightenment as De Morgan understood and visualized it.

Figure 2: The Kingdom of Heaven Suffereth Violence, and the Violent Take it By Force, Evelyn De Morgan (undated, c. 1900-1919)

The bottommost figures in the painting wear monochromatic, gray drapery and shirk away from the bright light above. They are surrounded by colorless, disembodied hell spirits, which Sophia De Morgan described as “always seen as black or grey, or of a leaden colour” that “cannot reflect the light of heaven.”[xi] Moving upwards, the figures’ drapery progresses from brownish gray, to violet, to indigo, to green, and then to orange, indicating enlightenment by degrees as they begin to look up. At the top of the composition, three white-clad figures actively reach upwards towards the light, where they will be freed from the confines of the physical body—like the heavenly spirits who accompany them—and enter the plane of invisible light that stretches beyond the canvas—and beyond the visible spectrum.

The colors of the four central figures appear in the order of the rainbow spectrum as discussed by Babbitt, and their placement on the canvas even mirrors Babbitt’s characterization of the visible spectrum as “colors which fall upon a screen in an oblong rainbow-colored form…the red being refracted least and the violet most from a straight line.”[xii] The journey to enlightenment begins with the violet-clad figure, who is farthest from the light and still bears the chains and golden crown that indicate worldliness. Violet light reacts the farthest from the white light, which comprises the full spectrum of colors and symbolizes the fulness of spiritual growth. Babbitt also demonstrated that “dazzling white” light represents the highest and most “heaven-facing” faculties of the brain, encompassing spiritual fullness through the harmony of all constituent colors of the rainbow and their associated qualities.[xiii]

The violet-clad figure is the farthest away from achieving this fullness. This parallels Babbitt’s assertion that violet light waves refract the farthest and “penetrate more deeply” than the other colors on the spectrum, with red light reaching and penetrating the least.[xiv] If a viewer is to understand that the repeated figure in The Kingdom of Heaven is growing increasingly permeable to spiritual enlightenment, it follows that her drapery would first be penetrated by the violet light. Each successive color then acts as a rainbow bridge from total darkness and impermeability, across the visible spectrum of colors, to the composite wholeness of full enlightenment.

Spiritual Auras and “Psychic Lights and Colors”

Just as the rainbow spectrum can only be seen by refracting light through a prism, it was understood that a person’s spiritual aura indeed existed in the physical world but could only be seen by someone in a trance-like state. Evelyn De Morgan painted two chromatically opposite, yet thematically connected, works that visualize spirit auras. These works demonstrate how De Morgan’s personal understanding of light symbolism was likely shaped by the scientific and Spiritualist discourses of her day, as well as the early modernist notion that light and color could be used as vehicles for emotional expression, not just physical representation, in art. Characterized by warm tones, Angels Piping to the Souls in Hell portrays spirits ascending to heaven. Our Lady of Peace utilizes cool tones in its portrayal of spirits descending to the earth. Both images appear to explore the concept of the spiritual aura, visualized in the colorful curves of light described by Edwin D. Babbitt, Sophia De Morgan, and in The Result of an Experiment.

What may have been especially fascinating to a Spiritualist like Evelyn De Morgan is Babbitt’s scientific interpretation of the concept of spiritual auras. He asserted in The Principles of Light and Color that humans radiate colored energy in the form of “psycho-magnetic curves” (Fig. 3) or “psychic lights and colors.”[xv] In a new scientific discipline he called “chromo-mentalism,” Babbitt explained that psychological force projects from the brain and manifests as a system of curved rays of light.[xvi]

Figure 3: The Psycho-Magnetic Curves, Edwin D. Babbitt (1878)

Interestingly, Babbitt elaborated, “The psychic lights and colors are inexpressibly beautiful and manifest the infinite activities of nature unseen by ordinary eyes…. This higher vision exalts the conception and shows that there is a grander universe within the visible.”[xvii] Babbitt’s inclusion of this discussion demonstrates that the connection between light and color waves and psychological expressions was not only determined by Spiritualists, but also by scientists. Both Babbitt and Sophia De Morgan utilize empiric language and present their information scientifically and authoritatively; despite the subjects and authors, the tone and vocabulary between the two is not notably different. From Matter to Spirit described the spiritual aura, which can be seen by spirit mediums, as “the gathering of the life-force or nerve-spirit from every part of the body in the head, where it again reissues…[as] a stream of electric light…passing from the head.”[xviii] Similarly, in The Result of an Experiment, spiritual auras are described as “flames” which “come round people like halos, only fanned by motion.”[xix] And, much like the refraction of light waves through a prism, From Matter to Spirit also documented the appearance of “spiritual influx” as “falling in regular waves corresponding to the waves of light.”[xx]

Babbitt’s research also asserted the unique properties and healing capabilities of different colors of light. He concluded that colored lights on the red, or thermal, end of the visible spectrum had the effect of being “exciting to the blood” and, in contrast, colored lights on the violet, or electric, end of the spectrum were “cooling and soothing to the nerves.”[xxi] From Matter to Spirit explained a similar phenomenon within the context of Spiritualism: “When a departed spirit is tranquil in its mind, its touch is felt to be like the softness of a cool air, exactly as when the electric fluid is poured upon any part of the body.”[xxii]

Figure 4: Angel Piping to the Souls in Hell by Evelyn De Morgan (undated, c. 1900-1919)

Angel Piping to the Souls in Hell (Fig. 4) depicts curves of hot light that undulate around the flaming, disembodied heads of agitated spirits. The swirls of light thrust the spirits up towards the piping angel, who leads their journey from the craggy landscape of hell towards heaven beyond the canvas. The thermal tone of this painting perhaps indicates, in Babbitt’s terms, an “excitement of the blood.” The spirits are rapidly “growing up into the light” and taking the next step in their spiritual evolution, which requires them to reckon with and leave behind their earthly sorrows and regrets. Visually, this painting also echoes a passage from The Result of an Experiment, wherein a spirit described seeing Evelyn De Morgan’s spiritual aura. It said: “[Evelyn] is red in her flames; [it] means a very strange sudden growth.”[xxiii] In this painting, the fiery light accompanies a frenetic host of hell spirits, whose spiritual stagnation has been suddenly disrupted by the piping angel, who catalyzes their rapid heavenward ascent.

Figure 5: Our Lady of Peace by Evelyn De Morgan (1902)

Our Lady of Peace (Fig. 5) Acting as a foil to Angel Piping to the Souls in Heaven, Our Lady of Peace (Fig. 5) depicts a soldier to whom the Virgin Mary appears to answer his prayer. Like the piping angel, Mary is ushering in the healing light of spiritual enlightenment, which curves in rainbow lines around her figure and towards the soldier. In contrast to the fiery hues of the piping angel, this swirling aura carries cooler tones and the disembodied heads of heavenly spirits, perhaps indicating a “soothing of the nervous system” bestowed upon the soldier, who is desperate for peace in wartime. Like violet light on the visible spectrum, the message traveled far from its spiritual source to reach its physical destination. The white vibrational lines of Mary’s halo suggest the fullness of her spiritual enlightenment that is revealed by degrees to the soldier as a source of comfort from the spirit world.

The same concept applies to how the composite colors of the visible spectrum add up to the wholeness of white light, its parts only revealed and understood through the use of a glass prism. Similarly, a spiritual aura can only be seen when the visible world is altered, whether through technology or clairvoyance. To Babbitt, such phenomena proved that discoverable parts of the material world, including the fullness of light, are invisible to the naked eye. To De Morgan, the same phenomena helped give form to her interoperation and visualization of spiritual enlightenment.

For Evelyn De Morgan, art—much like a prism—was the tool by which she explored the crossroads of the seen and the unseen, the physical and the spiritual, and the darkness and the light. The observation that De Morgan’s work contains “a thousand secrets” may always remain accurate. But it is worth considering how Victorian discourse on science and Spiritualism informed the way De Morgan used light as a recurring, personalized symbol in her later paintings. After De Morgan’s death, conversations surrounding her work largely focused on aesthetic comparisons to her second-generation Pre-Raphaelite peers like Edward Burne-Jones, to whom some of her work was even posthumously misattributed, and through the lens of her studies in London and travels to Florence. Adequate attempts to contextualize her work within the context of mainstream Victorian culture were not made for decades, in part because Wilhelmina Stirling’s efforts to collect and preserve her sister’s work inadvertently kept it out of public view.

It is worth investigating how external factors helped materialize the unique aesthetic and symbolic way in which Evelyn De Morgan understood the process of “growing up into the light” as an artist and as a Spiritualist. Cross-disciplinary consideration of her later paintings especially demonstrates her engagement with contemporary discourses on Spiritualism, science, and the infinitely rich intersection of the two realms, wherein De Morgan visualized her lifelong quest to reconcile the material and the mystical, and to “grow up into the light” herself.

Endnotes

[i] Alex Owen, The Darkened Room: Women, Power and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1989), 5.

[ii] Elise Lawson Smith, Evelyn Pickering De Morgan and the Allegorical Body (Cranberry and Missauga: Associated University Presses, 2002), 24.

[iii] On August 31, 1878, the same year Babbitt’s Principles of Light and Color was published in the United States, the London newspaper The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art published a multi-page review of the book in its “American Literature” section (pages 288-290)

[iv] A. M. W. Stirling, William De Morgan and His Wife (London: Thornton Butterworth Limited, 1922), 386. The author of this biography is Evelyn De Morgan’s younger sister, Wilhelmina Pickering Stirling. Elise Lawton Smith in Evelyn Pickering De Morgan and the Allegorical Body (Cranbury and Missauga: Associated University Presses, 2002) notes the importance of recognizing the bias and limitations of Stirling’s account of the De Morgans’ lives. However, Stirling’s biography is among the few available primary sources related to Evelyn De Morgan, so it remains a useful albeit anecdotal resource (Smith, 17-18).

[v] The Result of an Experiment (London: Simkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd., 1909). This book, published anonymously by William and Evelyn De Morgan, contains transcriptions from the couple’s automatic writing sessions.

[vi] Stirling 1922, 34.

[vii] Sophia De Morgan, From Matter to Spirit: The Result of Ten Years’ Experience in Spirit Manifestations (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, 1863), 64.

[viii] Edwin D. Babbitt, Principles of Light and Color (New York: Babbitt & Co., 1878), 66.

[ix] Sophia De Morgan 1863, 110.

[x] The Result of an Experiment 1909, 8.

[xi] Sophia De Morgan 1863, 302.

[xii] Babbitt 1878, 58.

[xiii] Babbitt 1878, 476-478.

[xiv] Babbitt 1878, 378.

[xv] Babbitt 1878, 113 & 481.

[xvi] Babbitt 1878, 468.

[xvii] Babbitt 1878, 527-528.

[xviii] Sophia De Morgan 1863, 131.

[xix] The Result of an Experiment 1909, 20.

[xx] Sophia De Morgan 1863, 352.

[xxi] Babbitt 1878, 67.

[xxii] Sophia De Morgan 1863, 105.

[xxiii] The Result of an Experiment 1909, 178.

Bibliography

“American Literature.” Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art

(London, United Kingdom). August 31, 1878.

Babbitt, Edwin D. Principles of Light and Color. New York: Babbitt & Co., 1878.

https://archive.org/details/PrinciplesOfLightAndColor.

De Morgan, Sophia. From Matter to Spirit: The Result of Ten Years’ Experience in

Spirit Manifestations. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, 1863.

https://archive.org/stream/frommattertospi04morggoog#page/n7/mode/2up.

Owen, Alex. The Darkened Room: Women, Power and Spiritualism in Late

Victorian England. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Smith, Elise Lawton. Evelyn Pickering De Morgan and the Allegorical Body.

Cranbury and Missauga: Associated University Presses, 2002.

Stirling, A. M. W. William De Morgan and His Wife. London: Thornton

Butterworth Limited, 1922.

The Result of an Experiment. London: Simkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co.,

Ltd., 1909.