Lenguaje, Llengua, y La Vanguardia: Avant-gardism in Barcelona and Madrid from 1915 to 1925

Le Yin

Citation: Yin, Le. “Lenguaje, Llengua, y La Vanguardia: Avant-Gardism in Barcelona and Madrid from 1915 to 1925.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, September 9, 2022. https://cmsmc.org/publications/lenguaja-avant-garde.

Abstract: Utilizing the work of Ramón Gómez de la Serna and Joan Miró as illustrative examples of their intellectual circles, this essay builds a dialogue between avant-garde practices in Madrid and Barcelona from 1915 to 1925 to identify the similarities in their linguistic practices and differences in ideologies. In the context of this essay, the word “language” in Spanish, lenguaje, and in Catalan, llengua, serve as signifiers for the artistic languages of Gómez de la Serna and Miró respectively. And departing from the literal meaning of these two words, these two signifiers help to further elucidate the thesis of this paper: while on the level of artistic practice both Miró and Gómez de la Serna were engaged with a kind of artistic avant-gardism involving the play of language, on the conceptual level, the lenguaje of Gómez de la Serna differed from the llengua of Miró.

Keywords: Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Joan Miró, avant-guardism, symbolism, Spain

In 1915, frustrated by the nihilism of the Generation of ’98, the Generation of ’14 was at the height of saving the Spanish nation on their own terms.[1] Different from the previous generation’s obsession with mysticism and the Nietzschean celebration of apocalypse, the Generation of ’14 advocated rationalism, science, and order. It was in this year that Diego Rivera (1886-1957) traveled to Madrid and painted a portrait for his friend Ramón Gómez de la Serna (1888-1963), an avant-garde literary figure active synchronously with José Ortega y Gasset’s (1883-1955) generation.

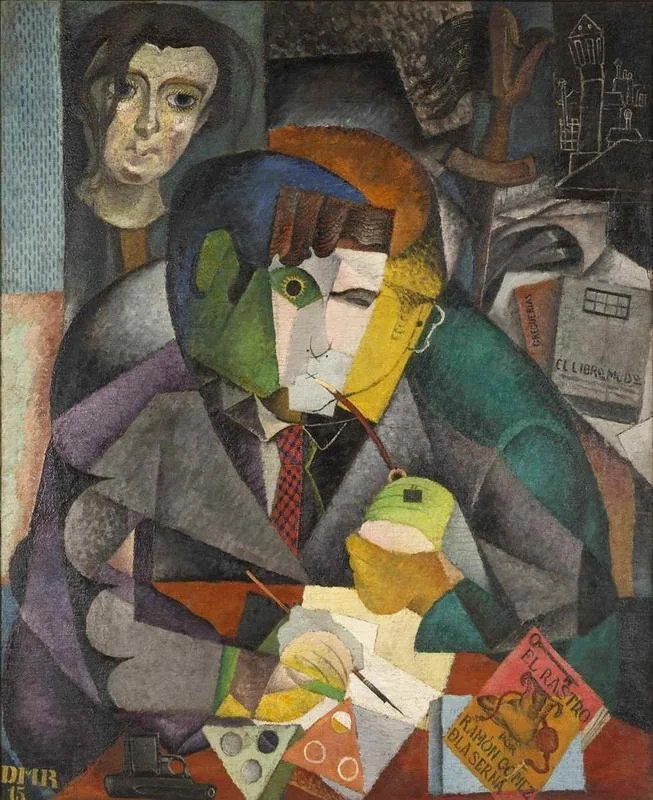

Figure 1: Diego Rivera, Portrait of Ramón Gómez de la Serna, 1915, oil on canvas, MALBA, Buenos Aires, Public Domain.

In his Portrait of Ramón Gómez de la Serna (Figure 1), Rivera depicted the poet Gómez de la Serna as sitting at his writing desk. Following Cubist aesthetics, that is, a bringing together of different views of subjects which creates an abstracted and fragmented visual effect, the portrait represents Gómez de la Serna through both surrealistic and realistic facets simultaneously. Realistically, Gómez de la Serna is dressed in a bourgeois suit; surrealistically, he is portrayed as a mythical figure with green skin and blue hair. In the background, Rivera depicts Gómez de la Serna’s collection of “goodies” acquired from the flea market – an uncanny mannequin, an abstract architectural drawing, and a stage prop evoking a quixotic sense of chivalry. These constitute a bizarre collage that resembles other surrealist (and Dadaist) collections in the likes of Paris. A copy of El Rastro (The Flea Market) sits on Gómez de la Serna’s desk, a book he published a year prior to the painting’s creation, and a revolver. The revolver symbolizes Ramón Gómez de la Serna’s identity as an aesthetic outlaw ─ a person who destroys the previous narrative of art to generate a new one. It also alludes to Joan Miró’s declaration, “I want to assassinate painting,” which showcases Miró’s determination to subvert the traditional institutionalized and bourgeois conception of painting.[2]

In addition to their similar wish “to assassinate” art, both Gómez de la Serna and Miró experimented with theories of language and linguistics. Gómez de la Serna created greguerías, a short form of poetry that deconstructs the conventional use of language and includes aphorism in one sentence, and Miró constructed an imaginary language through his paintings. However, because of their different localities, Gómez de la Serna and Miró’s projects show different ideological agendas. Based in Madrid, where the atmosphere of avant-gardism was conservative and largely influenced by the elitist model of José Ortega y Gasset, Ramón Gómez de la Serna’s work was restricted by his aestheticist retreat and his “structured blindness,” caused by his bourgeois background. [3] Since Joan Miró was a Catalan artist living and working in Barcelona, where the avant-garde practice coincided with Catalan nationalism, the visual language embedded within his paintings is essentially nationalistic.

Utilizing the work of Ramón Gómez de la Serna and Joan Miró as illustrative examples of their intellectual circles, this essay builds a dialogue between avant-garde practices in Madrid and Barcelona from 1915 to 1925 to identify the similarities in their linguistic practices and differences in ideologies. In the context of this essay, the word “language” in Spanish, lenguaje, and in Catalan, llengua, serve as signifiers for the artistic languages of Gómez de la Serna and Miró respectively. And departing from the literal meaning of these two words, these two signifiers help to further elucidate the thesis of this paper: while on the level of artistic practice both Miró and Gómez de la Serna were engaged with a kind of artistic avant-gardism involving the play of language, on the conceptual level, the lenguaje of Gómez de la Serna differed from the llengua of Miró. Gómez de la Serna’s lenguaje shows an elitist aesthetic retreat, a turning away from the violent social struggles happening to lower class Spanish people, but Miró’s llengua represents Catalan nationalism, which attempts to embrace all Catalan people regardless of their social class ostensibly but entails the middle-class artist’s alienated imagination of the rural area of Catalonia.

To elucidate this argument, I first analyze the avant-gardist circle of Madrid and its internal differences within this circle, notably between Gómez de la Serna and José Gutiérrez Solana, a Spanish painter in the same avant-garde circle with Gómez de la Serna. I follow this with a discussion of the linguistic avant-gardism of Miró. Finally, I conclude that the avant-gardist practices of both Gómez de la Serna and Miró were unsuccessful in constructing an avant-gardism that communicates with the Spanish and Catalan people regardless of their social class due to the artists’ “structured blindness,” ─ based upon Epps’s definition concerning the epistemological bias of artists caused by their socio-economic background. For this reason, the artists were ignorant of the struggles of lower-class Spanish and Catalan people and failed to empathize with or (re-)present the latter’s situation accurately.

Before the civil war, the comparatively peaceful situation in Spain due to the nation’s neutrality during World War I and the robust cultural atmosphere boosted by the Generation of 14' led to an increase in cafés around the country. Cafés were important institutions for intellectual gatherings and gradually became a major symbol of modernity. Among those cafés was Café Pombo, located on Calle Carretas in Madrid, next to Puerta del Sol. From 1915, this café became the venue for intellectual gatherings held by Ramón Gómez de la Serna, frequented by leading figures of the avant-garde scene in Madrid such as José Gutiérrez Solana (1886-1945), an artist who painted a gathering at Café Pombo, La tertulia del Café de Pombo in 1920.

The amalgamation in Solana’s painting shows the artist’s ambivalence towards a radical avant-gardism that “assassinates” the past. Solana’s painting shows participants in a Pombo gathering as bourgeois gentlemen dressed in fine suits, echoing how Gómez de la Serna was dressed in the portrait by Rivera. At the center of the scene stands Gómez de la Serna, holding his book Pombo, which was published in 1918 and explored his experience in literary gatherings at this Café. Signified by their fixed eyes and erect bodies, the gentlemen in this painting appear determined, suggesting their resolution to change the torpor of Spanish culture through their avant-gardism. Solana’s painting presents a coded language, or a closed system of visual signs with designated denotations and connotations, that is a confluence of modernity and tradition. While the painting’s composition resembles that of 17th-century Dutch group portraits, revealing the painter’s orthodox fine arts background, the depicted subjects are modern intellectuals instead of ruling regents or militia members. This choice of composition and substitution of subjects could be suggesting that for Solana, the modern intellectuals were the new ruling regents of the age. In the framed mirror-like portrait hanging on the wall, the sitters are dressed in passé clothes of the 19th-century, contrasting those modern suits of the gentlemen in the foreground. Placed on the left and right side of the mirror-like portrait are an old mechanical fan and a modern electric light respectively. This further juxtaposes the two generations and shows the artist’s orthodox training.[4]

Like elements from the past that linger on his canvas, Solana was reluctant to give up tradition, as well as the advantage of his bourgeois class. However, although both de la Serna and Solana were members of those gatherings at Café Pombo, Gómez de la Serna’s attitude towards the past and his conception of avant-gardism differed from those of Solana. As the revolver in the foreground of his portrait by Rivera suggests, de la Serna wished to break from tradition and embrace a new radical reality of the avant-garde.

The avant-gardism of Ramón Gómez de la Serna is exemplified by his greguerías, a literary experimentation he started at around 1910 (continued until 1960, and published Total de greguerías in 1955). For Gómez de la Serna, the greguería is an attempt to capture illogical utterances and to investigate the unconscious, similar to the surrealist school, a group of artists that explored the unconscious and the irrational in their artworks, starting in early 20th-century.[5] An example of de la Serna’s greguería is:

“El filósofo antiguo sacaba la filosofía ordeñándose la barba.”[6]

Translated to: “The ancient philosopher drew philosophy out by milking his beard.”[7]

In this greguería, Gómez de la Serna compares the ancient philosopher’s process of philosophizing to that of milking. To Gómez de la Serna, the arduous process of philosophizing resembles the heavy labor of milking, and how the milk comes out dripping bit by bit. Additionally, the greguería becomes a sensual expression that includes the sense of touch (a philosopher touching his beard, milking), the sense of smell, taste, and sight (the milk), within one sentence. By this, Gómez de la Serna juxtaposed two disparate activities and linked them, challenging the intuitive use of language on an unconscious level.

Gómez de la Serna’s greguerías break the convention of language, which is a closed symbolic system that denotes, signifies, and represents following conventional rules. However, the greguerías detach language from its conventional rules, experiment with unconventional possibilities of metaphors and analogies, and focus on a sense of randomness through the play of language. In Gómez de la Serna’s greguerías, words and phrases become flexible modules mixed with one another and free from conventional rules of language – a signifier signifies something that it does not ordinarily indicate. For example, in a greguería by Gómez de la Serna, the “leaves” that are falling in autumn are not only leaves from a tree but also those of a book.[8] To some extent, the poetic language of Gómez de la Serna is no longer “representational” as modules (i.e., words and phrases) of his sentences don’t “represent” the scenario they usually do, parallel to how for José Ortega y Gasset, in modern art, modules of paintings, i.e., abstract forms and colors, are not “representational” as they no longer “represent” objects or scenes existing in reality.

In The Dehumanization of Art, José Ortega y Gasset compares modern art to Romanticism. By modern art, Ortega y Gasset referred to nonrepresentational avant-garde artworks by his contemporaries, and by Romanticism, he meant the representational artform before the avant-garde. For Ortega y Gasset, the representational nature of Romanticism makes it “very quick in ‘winning the people’,” since one can look clear through a Romanticist painting and see it as what it depicts. Thus, the viewer simply needs to appreciate the recognizable scenes in Romanticist works: “paintings attract him if he finds on them figures of men or women whom it would be interesting to meet. A landscape is pronounced ‘pretty’ if the country it represents deserves for its loveliness or its grandeur to be visited on a trip.”[9]

While Romanticism is about a representation of human reality, modern art deviates from art’s representational function and creates a reality of art’s own: a process Ortega y Gasset calls “the dehumanization of art.” And in contrast to the popularity of Romanticism, for Ortega y Gasset, modern art is “antipopular” with its audience as it was “dehumanized”.[10] As modern art shifted away from the Romantic perspective, it aimed to challenge its audience, and make its audience feel outside of their comfort zone. Thus, it became unpopular with the latter. Because of modern art’s “antipopularity,” Ortega y Gasset further argues that modern art can actively divide the shapeless mass into “two different castes of men:” 1. the “mass men,” who could not appreciate modern art and would never accept authority external to themselves, and 2. the “select men,” who could appreciate modern art, were critical thinkers, and were willing to listen to, empathize with, and understand innovative ideas. By this, Ortega y Gasset bestows a sense of agency upon modern art. Modern art transmutes to a Subject that can act and divide the shapeless mass. To Ortega y Gasset, Gómez de la Serna’s literary practice is modern, and thus dehumanized, because it deconstructs the standpoint of ordinary human life.

The discussion about the change of standpoint is also at the center of Ortega y Gasset’s philosophy. While for the modern visual arts, the required switch of apparatus is about focusing on art’s presentational forms as opposed to its denotational meanings, in modern literature, it is about the subversion of perspective in the use of language: “To satisfy the desire for dehumanization one need not alter the inherent nature of things. It is enough to upset the value pattern and to produce an art in which the small events of life appear in the foreground with monumental dimensions.”[11] As in the aforementioned greguería, intellectual labor is juxtaposed with physical labor, allowing Gómez de la Serna to break the hierarchy of the dualism of mind and body.

In November 1921, Ortega y Gasset expressed his gratitude for Gómez de la Serna’s work in a speech at Café Pombo. In this speech, Ortega described the Pombo circle as “the last barricade” before the rebellion of the masses. And this speech was published in Ultra, the major journal of the Generation of ’14, a month later. However, as pointed out by Domingo Ródenas de Moya, the well-measured language Ortega used in the speech suggests his lack of confidence in those “shaggy vanguardists.”[12]

Ortega y Gasset’s speech recognized the Pombo circle’s effort to “demolish the last, almost imperceptible vestiges of literary tradition,”[13] but he did not see this circle as capable of initiating a new tradition that could save the torpor of Spanish culture. Instead, he placed his hopes on the next generation to “gather together building blocks to demand a new tradition.”[14] This could suggest the subsequent Generation of ’27, which included Salvador Dalí (1904-1989), Federico García Lorca (1898-1936), and Luis Bruñuel (1900-1983), who were students at the Residencia de Estudiantes at that time.[15] However, because Ortega y Gasset praised the individual work of Gómez de la Serna, rather than his Pombo circle as a whole again four years later in The Dehumanization of Art, it is reasonable to deduce that, for Ortega y Gasset, there was a difference between the avant-gardism of de la Serna and that of other more conservative members in the Pombo circle like Solana.

This is not to say that the art of Ramón Gómez de la Serna was successful in changing the torpor of Spanish culture and initiating a new intellectual generation that communicated to all people regardless of their class. Like Ortega y Gasset’s elitism, which placed his hopes for a cultural and social reform on the “select men,” which referred to essentially intellectual elites, de la Serna’s work only spoke to the “select men,” like modern artists, for its intellectual requirement.[16] Although, as is written in The Revolt of the Masses, Ortega y Gasset’s elitism targets whether a person can retreat from social norms and embrace a radical reality of the “self.” Ortega y Gasset’s bourgeois-class background determined his “structured blindness,” evident by the elitism inherent in his writing. He overlooked the unequal access to education based on class difference, which in turn caused the unequal possibility to “retreat” and become a “select man.” Ortega y Gasset’s model of intellectual elitism denies that it is about social class but is fundamentally based in classist assumptions.

Ortega y Gasset came from the family that controlled Madrid’s leading liberal newspaper, El Imparcial. Similarly, de la Serna was born into an upper-middle-class family – he lived the life of a bohemian artist, but his first literary journal Prometeo was funded by his father. The “structured blindness” of both Ortega y Gasset and Gómez de la Serna determined the biased and limited audience of their language. Also, in de la Serna’s literary practice, although he challenged conventions of language and literary traditions, which are inside the ivory tower of the intellectual discourse, he left the social distress during the crisis of the Restoration system and conventions of society unscathed.[17] Thus, to some extent, his work is an aestheticist retreat to the beauty of forms, suggests his passive turn away from Spain’s political and social turbulence, and indicates his tacit consent to the ruling status of his bourgeois class.

Moreover, Gómez de la Serna’s bourgeois bias is reflected by certain motifs in his writing, for example, in his Pombo (1918) and La Nardo (1930). At times, as the protagonist in La Nardo wanders around the streets of Madrid and collects bizarre objects from the flea market, the reader could easily relate him to the flaneur or the Baudelairean painter of modern life. To a large extent, Ramón’s literary practice was restricted by his bourgeois narcissism that revolves around his indulgence in l'art pour l'art.

Yet Madrid was not the only venue for avant-garde experimentation in Spain at that time. Compared to its rather conservative cultural atmosphere, the avant-garde scene in Barcelona was more vibrant, made possible by institutions such as the Galeries Dalmau. Contemporaneous with the Pombo tertulia and the Generation of ‘14, intellectual circles in Barcelona were investigating a language of art and avant-gardism. Different from the elitist lenguaje of Ortega y Gasset and de la Serna, the Catalan artist living and working in Barcelona, Joan Miró, developed his artistic llengua that tried to connect with a broader audience – “broader” in a sense that he made efforts to connect with people of different social classes through motifs of the peasantry in his paintings. Yet his llengua is also narrower, because he was constructing an avant-garde project that centered on Catalan nationalism, an ideology asserting the Catalans as a distinct nation that bolstered in the early 20th-century.

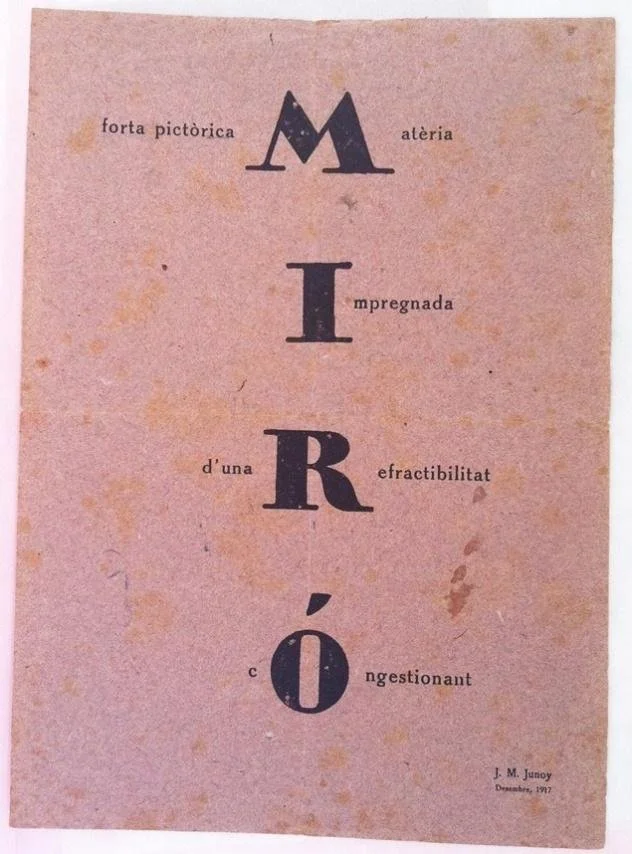

Figure 2: Josep Maria Junoy, Leaflet for the Miró exhibition at the Galeries Dalmau, 1918. Public Domain.

February of 1918 was an important month for Joan Miró. On February 16th, 1918, Galaries Dalamu inaugurated a solo exhibition of Miró that featured his artwork produced in the past two years and showed the artist’s dialogue with major contemporary art movements in Europe. It was also in this month that the Catalan literary journal about avant-garde art and literature Arc Voltaic published its first issue with cover art by Miró. In the Dalmau exhibition, a leaflet designed by Josep Maria Junoy (1887-1955) accompanied Miró’s art (Figure 2). It resembled the visual effect of concrete poetry.[18] On the leaflet, the name of Miró is encrypted into a sentence in Catalan that described the characteristics of his art: “forta pictòrica Matèria Impregnada d’una Refractibilitat cOngestionant,” or “strong pictorial matter saturated with a congestive refractivity” in English. [19] According to Lubar-Messeri, this calligram represents a complex linguistic system in Junoy’s work: 1. It stands as a proxy for Miró, 2. It is a condensed critique of Miró’s artwork, 3. It signifies the alliance between Miró’s art and Junoy’s literature in their shared cosmopolitan perspective and linguistic features, 4. It is written in Catalan, making the Catalan language a metonymy for modernity.[20]

The collaboration between Miró and Junoy at this exhibition was no coincidence. The two’s long friendship fit with their shared nationalistic ideal of avant-gardism, focusing on the intersection between painting and language. For example, in the cover art Miró designed for Arc Voltaic (Figure 3), there is a cryptic symbolic system that is merged with pictorial representation. At the center of the drawing, one sees a female nude with a voluptuous body. However, her body is not about sensual beauty. Elements such as the grotesque and mechanical curves at her back and stomach, her muscular and even aggressive thighs relate the drawing to Italian Futurism, an art movement originated in the early 20th-century that emphasized dynamism, speed, technological evolution, and progression.

Figure 3: Joan Miró, Cover art of Arc Voltaic, 1918. Courtesy of The Museum of Avant-garde. https://www.ma-g.org/artwork/42-arc-voltaic/?signup-banner=not-now

The female nude could also allude to Joaquim Sunyer’s (1874-1956) Pastoral, 1910-11, considering the similar posture of the nude and the latter’s canonical status in Catalan modern art and nationalism. While the nude in Sunyer’s painting is a personification of the Catalan landscape, the nude in Miró’s drawing becomes the personification of a different version of Catalonia: one that is a modern and progressive nation. The female nude is transmuted to an ideogram that signifies multiple meanings. In Miro’s drawing, the geometric mat on which she sits, and the electric wave emitted from the upper-right corner, both add to the theme of progression and modernity, a theme that echoes the dynamic urban environment which Joaquín Torres-García, another major contributor of Arc Voltaic, described in a lecture at the Galeries Dalmau.

The cover of Arc Voltaic showcases a wish for a modern, dynamic, and urban nation, aligned with the avant-gardist wish for Europeanization and cosmopolitanization in both Madrid and Barcelona. However, while in Madrid, exemplified by Ortega y Gasset’s philosophy, Europeanization meant science, logic, and order, in Barcelona, it meant cosmopolitan cultural practice that acted as a foil to what was a bona fide Catalan. Miró and Junoy’s work are examples of the latter, as the artists merged Cubism and Futurism with their own styles. In a 1920 letter to Enric C. Ricart, Miró expressed his wish to be an “international Catalan.” “You have to be an International Catalan,” says the artist, “a homespun Catalan is not, and never will be, worth anything in the world.” This proclamation made after the artist’s immigration to Paris showcases the artist’s wish to utilize cultural cosmopolitanism to set off Catalan nationalism. After all, the Catalan culture can only be examined as that of an individualistic nation when it is juxtaposed with other distinct national cultures.

Still, Miró’s project of Catalan nationalism could not be completed if he only targeted an international audience, so he also spoke to the Catalan people. Distinct from the elitist practices of avant-garde groups in Madrid, Miró made efforts to connect with people from different social classes. For example, in his The Farm, 1921 – 22, Miró depicted the countryside of Catalonia. This contrasts the modern, vibrant, and urban themes presented in Arc Voltaic’s cover art. In The Farm, Miró constructed a “visual index” based on his romanticized vision of rural Catalonia. Miró was never actually a Catalan peasant, but instead grew up in the Barri Gòtic neighborhood of Barcelona.[21] In this imaginative painting, motifs such as the plowed field, the farm implements, the livestock, and the country-style architecture, become ideograms like the nude on the cover of Arc Voltaic. In this case, the motifs signified the landscape of Catalonia, the hard-working Catalan people, Catalan nationalism, and a national myth under construction.

The painting is a collection of discrete details, each meticulously studied and documented in an almost scientific manner. To some extent, The Farm resembles a 17th-century Dutch cabinet of curiosities painting, or East Asian calligraphy as in a poem: as the former presents similar diligence in the documentation and the latter is a collection of ideograms. However, while in a cabinet of curiosities painting, the documentation is about treasures that are essentially objects, and in East Asian calligraphy, the collection is of characters that are symbols serving as parts of a written linguistic system, The Farm presents the collected and documented as tokens of Catalan peasants’ lives. The painting shows the artist’s alienation of the rural population – their lives are degraded into generic types.

Miró’s alienation of the rural makes his project of Catalan nationalism self-contradictory. As he claimed to unite all Catalan people regardless of their social class, his elitist standpoint as a Barcelonian artist limited his ability to empathize with the rural of the nation. Instead of engaging the peasantry in his avant-garde project, the artist used them as tools for constructing a national myth on his canvas. The avant-garde group’s proclamation gradually became an act of Sartrean Bad Faith.

Viewed from the perspective of social art history, avant-gardism from 1915 to 1925 was a failure in both Madrid and Barcelona because the artists limited their ideas and works to their own classes. However, to the ivory tower of literature and art, avant-garde groups in both localities were groundbreaking in discovering a new direction for their practice, that is, to engage with and challenge linguistics. Through their lenguaje and llengua, artists in both Madrid and Barcelona participated in the cosmopolitan avant-gardisms that revolved around the artful use of language. A dialogue with artistic practices related to linguistics and language in other European localities, besides Spain and Catalonia, may further illuminate the cosmopolitan nature and philosophical depth of avant-gardism in both Madrid and Barcelona.

Endnotes:

[1] The generation of ’98 was a group of Spanish intellectuals active at the time of the Spanish-American war, committed to cultural and aesthetic renewal and modernist practice. The generation of ’14 was an evolution from the previous generation of writers who advocated science and other modern standards.

[2] Robert Lubar-Messeri, "Art and Anti-Art: Miró, Dalí, and the Catalan Avant-Garde," in Barcelona and Modernity: Picasso, Gaudí, Miró, Dalí, William H. Robinson ed. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2006), 345.

[3] Brad Epps, “Seeing the Dead: Manual and Mechanical Specters in Modern Spain (1893-1939),” in Visualizing Spanish Modernity, Susan Larson and Eva Woods ed. (Oxford: Berg, 2005).

[4] The mirror-like portrait could be alluding to Velázquez’s Las Meninas, in which silhouettes of King Philip IV and Queen Mariana are depicted in a mirror directly opposite the viewer.

[5] Richard L. Jackson, "The Surrealist Image in the 'Greguería' of Ramón Gómez de la Serna," Romance Notes 8, No. 1 (1966): 12. Jackson cites Gómez de la Serna’s own definition of the greguería from the latter’s Total de greguerías (Madrid: Aguilar, 1955), p. xxvii.

[6] Jackson 1966, 12. Jackson cites from Ramón Gómez de la Serna’s Total de greguerías (Madrid: Aguilar, 1955), p. xxvii.

[7] Jackson 1966, 12. Translated to English by Le Yin.

[8] Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Total de greguerías, (Madrid: Aguilar, 1955), 15.

[9] José Ortega y Gasset, The Dehumanization of Art and Other Essays on Art, Culture, and Literature, (Princeton University Press, 2019), 5.

[10] Ortega y Gasset 2019, 5.

[11] Ortega y Gasset 2019, 35.

[12] Domingo Ródenas de Moya, “The Invention of an Avant-Garde Readership,” in Avant-Garde Cultural Practices in Spain (1914-1936), Eduardo Gregori and Juan Herrero-Senés ed. (2016, Brill), p. 26.

[13] Ródenas de Moya 2016, 26. Quotes from Ortega’s speech.

[14] Ródenas de Moya 2016, 26.

[15] The Residencia de Estudiantes literally means the “Student Residence.” It was a cultural institution that helped to foster the intellectual environment of Spain before the Spanish Civil War.

[16] Ortega y Gasset 2019, Dehumanization.

[17] In 1917, the Spanish system of Restoration, that is, the restoration of the Spanish Monarchy since 1874, was challenged by the military movement of the Defence Juntas, the political movement of the Regionalist League of Catalonia in Barcelona, and the general strike of the public.

[18] It is possible that Junoy’s work was inspired by the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, whose concrete poetry collection, Calligrammes, was published in 1918.

[19] Translated by Lubar-Messeri 2006, 342.

[20] Lubar-Messeri 2006, 342-347.

[21] The phrase “visual index” is borrowed from Lubar-Messeri’s 2006, 342.

Bibliography

Epps, Brad. “Seeing the Dead: Manual and Mechanical Specters in Modern Spain (1893-1939). In Visualizing Spanish Modernity, edited by Susan Larson and Eva Woods, 112-162. Oxford: Berg, 2005.

Jackson, Richard L. “The Surrealist Image in the ‘Greguería’ of Ramón Gómez de la Serna.” In Romance Notes 8, no. 1 (1966), 11-13. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43800982.

Lubar-Messeri, Robert. “Art and Anti-Art: Miró, Dalí, and the Catalan Avant-Garde.” In Barcelona and Modernity: Picasso, Gaudí, Miró, Dalí, edited by William H. Robinson, 339-347. New Haven and London: The Cleveland Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2006.

de Moya, Domingo Ródenas. “The Invention of an Avant-Garde Readership.” In Avant-Garde

Cultural Practices in Spain (1914-1936), edited by Eduardo Gregori and Juan Herrero-Senés, 13-34. Boston: Brill, 2016.

Ortega y Gasset, José. The Dehumanization of Art and Other Essays on Art, Culture, and Literature. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019.

Ortega y Gasset, José. The Revolt of The Masses. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1994.

Wohl, Robert. “Spain: The Theme of Our Time.” In The Generation of 1914, Boston: Harvard University Press, 1979.