Abolitionist Broadsides and Anti-Slavery Imagery

Abigail Epplett

Citation: Epplett, Abigail. “Abolitionist Broadsides and Anti-Slavery Imagery.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, June 17, 2022.

Note: This article is derived from a presentation given at the 2021 CMSMC Symposium entitled, “Crime and Spectacle: Theft, Forgery, and Propaganda,” which is available to view on our website at cmsmc.org.

Abstract: In the early nineteenth century, broadsides were a common form of mass media, which were produced in bulk and intended for single use – as such, few nineteenth-century broadsides have survived. Those preserved in collections give historians an inside look at the ideology of anti-slavery societies and pro-slavery institutions, along with documenting design sensibilities and imagery of historical propaganda. Broadsides published by anti-slavery societies advocated for immediate abolition. Surviving broadsides show their dedication to the cause, mixing established design with passionate writing and occasional imagery to capture and hold the reader’s attention. Yet, this passion cannot mask the way their message emphasized the superiority of its intended highly educated Northern white audience.

Keywords: broadsides, abolitionist propaganda, historical propaganda, mass media

In the first half of the nineteenth century, broadsides were a common form of mass media plastered throughout the streets of northern American cities. Produced in bulk and intended for single use, few nineteenth-century broadsides have survived. Those preserved in collections give historians an inside look at the ideology of anti-slavery societies and pro-slavery institutions, along with documenting design sensibilities and imagery of historical propaganda. Broadsides published by anti-slavery societies advocated for immediate abolition. They encouraged illegal activities, such as harboring freedom seekers, and announced upcoming anti-slavery conferences, rallies, and picnics. A combination of contemporary design and authoritative language allowed anti-slavery broadsides to proliferate throughout the North prior to the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment. Yet despite their radical messages, the language and imagery of these posters supported racial constructs and stereotypes held by many white, affluent abolitionists.

Anti-Slavery Societies and Target Audience

In 1807, the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves banned the Transatlantic Slave Trade.[1] However, the legality of slavery was decided at the state level, though the federal government could overturn that state law. Anti-slavery societies flourished in the North prior to the Civil War. These organizations originally consisted of white male membership. Though, eventually, women and African-Americans were encouraged to join, society leadership continued to be dominated by those in power.[2] The largest of these organizations was the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), founded in 1833 and led by William Lloyd Garrison. The radical Garrisonian abolitionists led public protests, organized widely attended conferences, and gave compelling speeches to their white target audience.

Extant anti-slavery broadsides published by the AASS and similar societies mainly conform to the view of white, Garrisonian abolitionists. The language and design for these broadsides catered to Northern, middle class and affluent audiences who could contribute financially to the AASS. Besides bolstering the ideology, broadsides further encouraged abolitionist activity, despite its status as a federal crime after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.[3]

The Design and Language of Nineteenth-Century American Broadsides

The invention of steam-powered presses and steel engravings allowed publishers to increase printing capacity vastly in the first half of the nineteenth century.[4] Broadsides from this period follow a repetitive design scheme, an attempt to make the greatest possible visual impact at the lowest cost. Cheap paper, an eclectic collection of bold typefaces, minimal color, and sparse imagery defined the style. Notices about slave auctions and escapees were indistinguishable from anti-slavery material until the viewer examined and read the broadside, forcing even the unsympathetic to take a closer look at the practice of slavery.

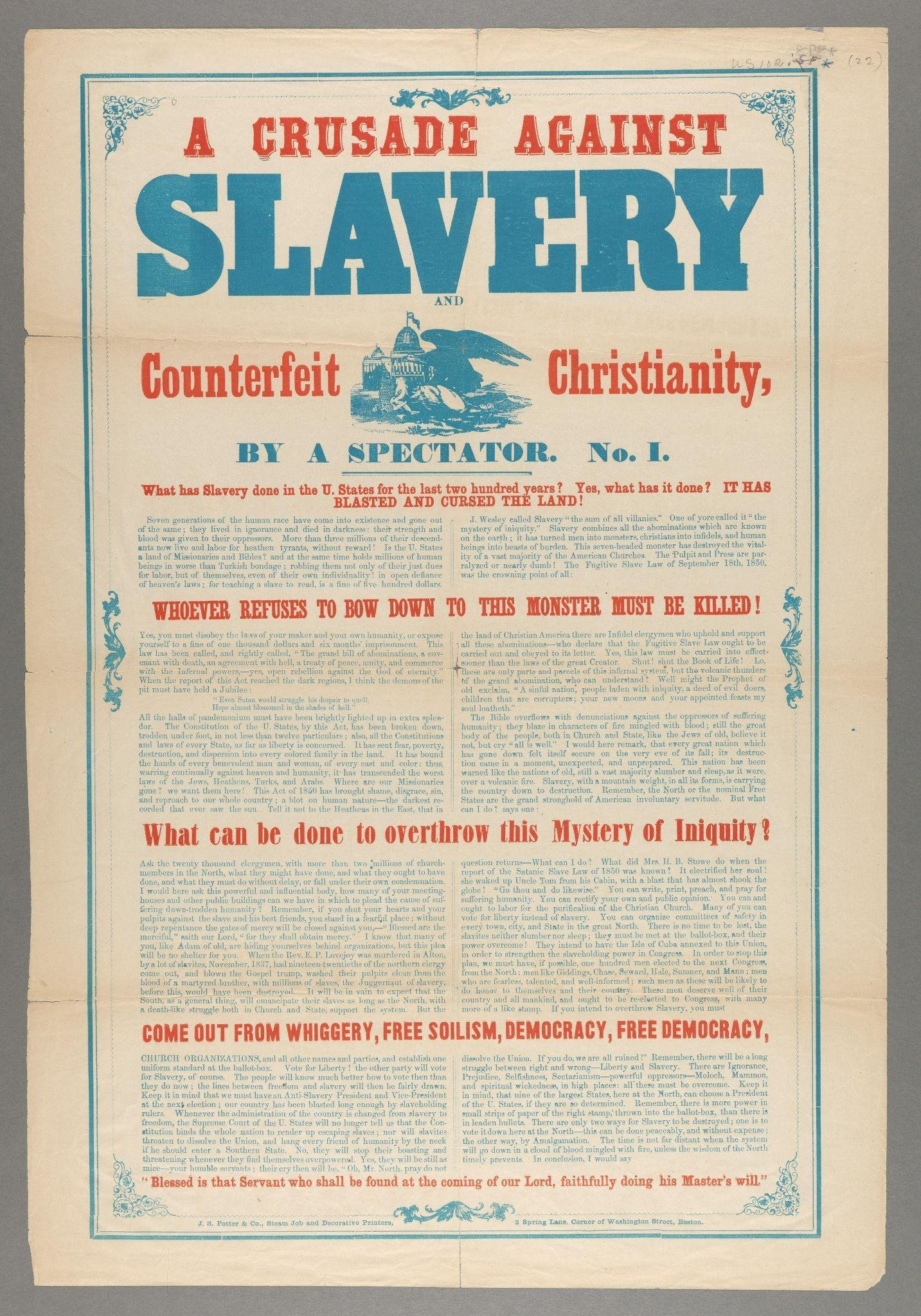

Broadside authors used hyperbole and purple prose vehemently arguing a heavily biased opinion. An example comes from this two-tone broadside published after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 [Fig. 1], which proclaims:

There are only two ways for slavery to be destroyed; one is to vote it down here at the North – this can be done peacably, and without expense; the other way, by Amalgamation. The time is not far distant when the system will go down in a cloud of blood mingled with fire, unless the wisdom of the North timely prevents.

Fig. 1. J. S. Potter & Co., printers. A Crusade against Slavery and Counterfeit Christianity. 1850. Image. https://digitalcollections.library.harvard.edu/catalog/990050995450203941 (accessed May 25, 2022).

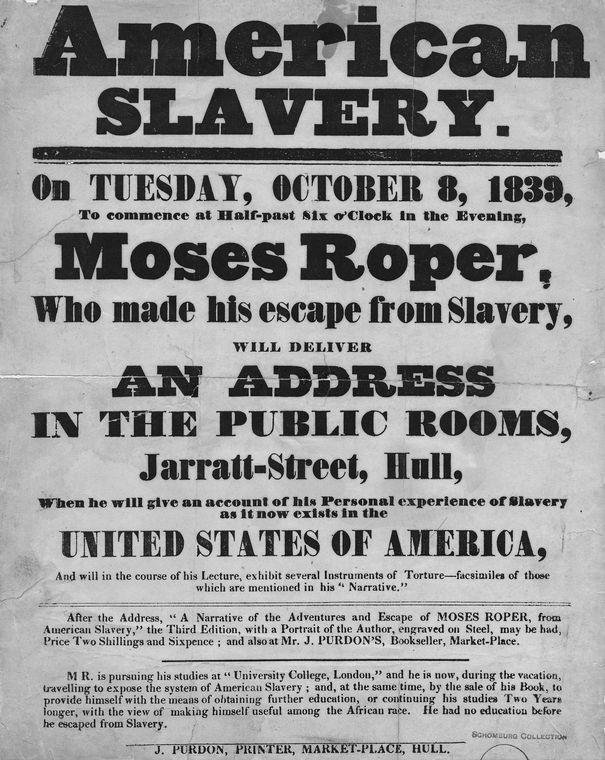

Fig. 2. American Slavery. Moses Roper. October 8, 1839. Image. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-c9e4-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed May 25, 2022)

Fig. 3. Means, John, and R. E. Stanley. $2,500 Reward. August 23, 1852. Image. http://collections.mohistory.org/resource/216610 (accessed May 25, 2022)

Abolitionist authors wrote for a white, educated audience, as they deftly combined their views on social issues with Biblical references. The phrase “a cloud of blood mingled with fire” is paraphrased from the King James Version of Revelations 8:7, “The first angel sounded, and there followed hail and fire mingled with blood…” This passage describing the start of the End Times would have been familiar to any casual passersby of the nineteenth century.[5] The omission of the South demonstrates the author’s belief that Southerners were unwise, even uneducated, in addition to being “slavites,” the author’s word choice for supporters of enslavement.

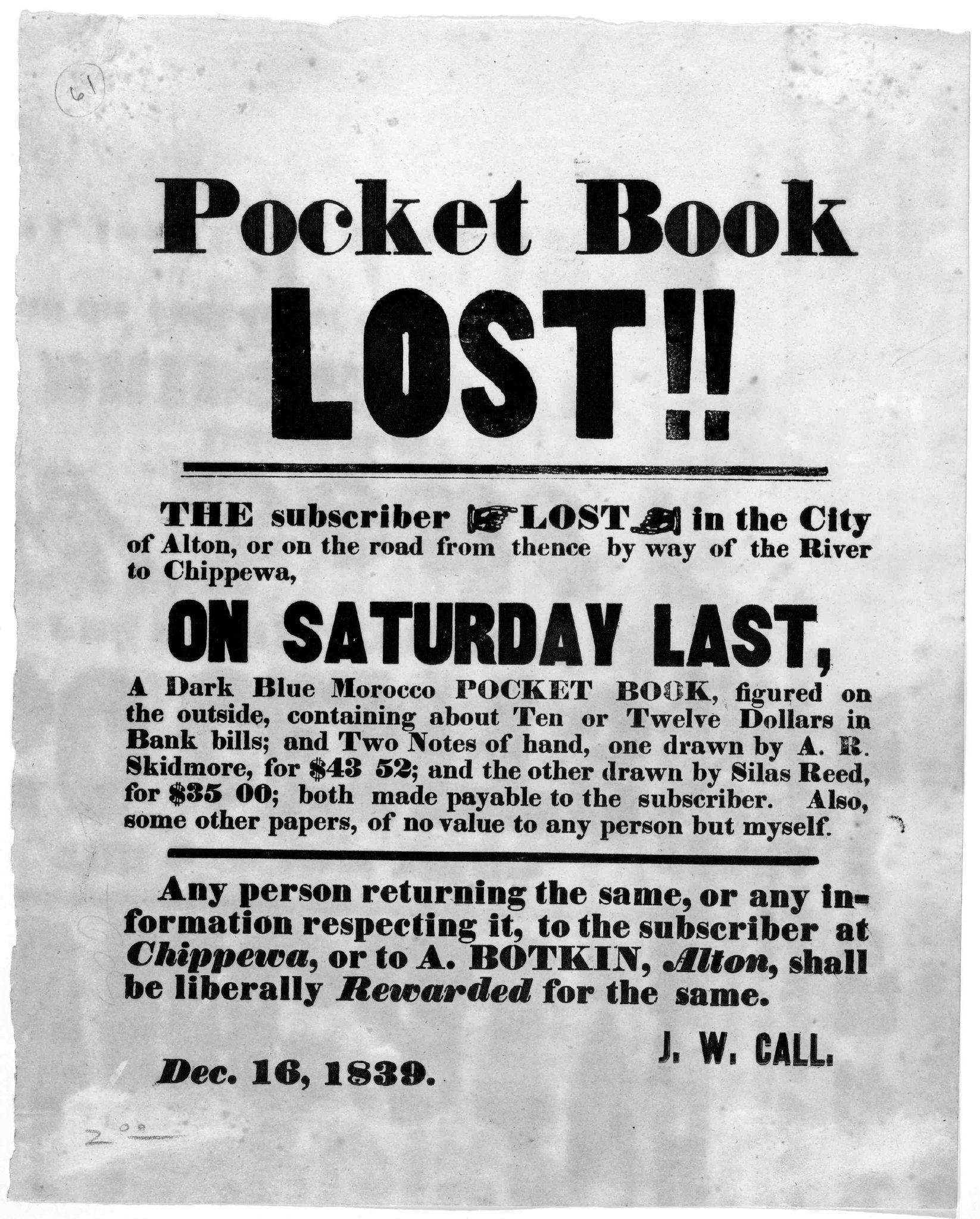

Fig. 4. Call, J. W. Pocket Book Lost!! December 16, 1839. Image. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.01501900/ (accessed May 25, 2022)

As seen in the two broadsides, “American Slavery… Moses Roper” [Fig. 2] and “$2,500 Reward” [Fig. 3], anti-slavery and pro-slavery broadsides share common mid-nineteenth-century designs. Both incorporate fat face fonts in the text and employ a mix of facts and exaggerations in descriptive paragraphs. Additionally, since illustrations required more time and ink, neither of these broadsides include detailed imagery, except for the simple yet graphic pointing hands on “$2,500 Reward,” an objectifying symbol commonly used on lost-and-found broadsides [Fig. 4]. Because of the similarity in design between broadsides, and especially with the absence of imagery, readers needed to inspect the prints to understand the motivations and message of the designer.

Abolitionist Imagery

Abolitionists developed a vocabulary of imagery for memorabilia distributed at events. These materials supported a Eurocentric narrative that enslaved African-Americans could only be rescued by whites, a viewpoint openly criticized by Black journalists and publishers.[6] Among the most compelling was Fredrick Douglass, whose fame as an intellectual and relationship to Garrison led white abolitionists to portray him as one of the few self-reliant Blacks in derogatory white abolitionist imagery.

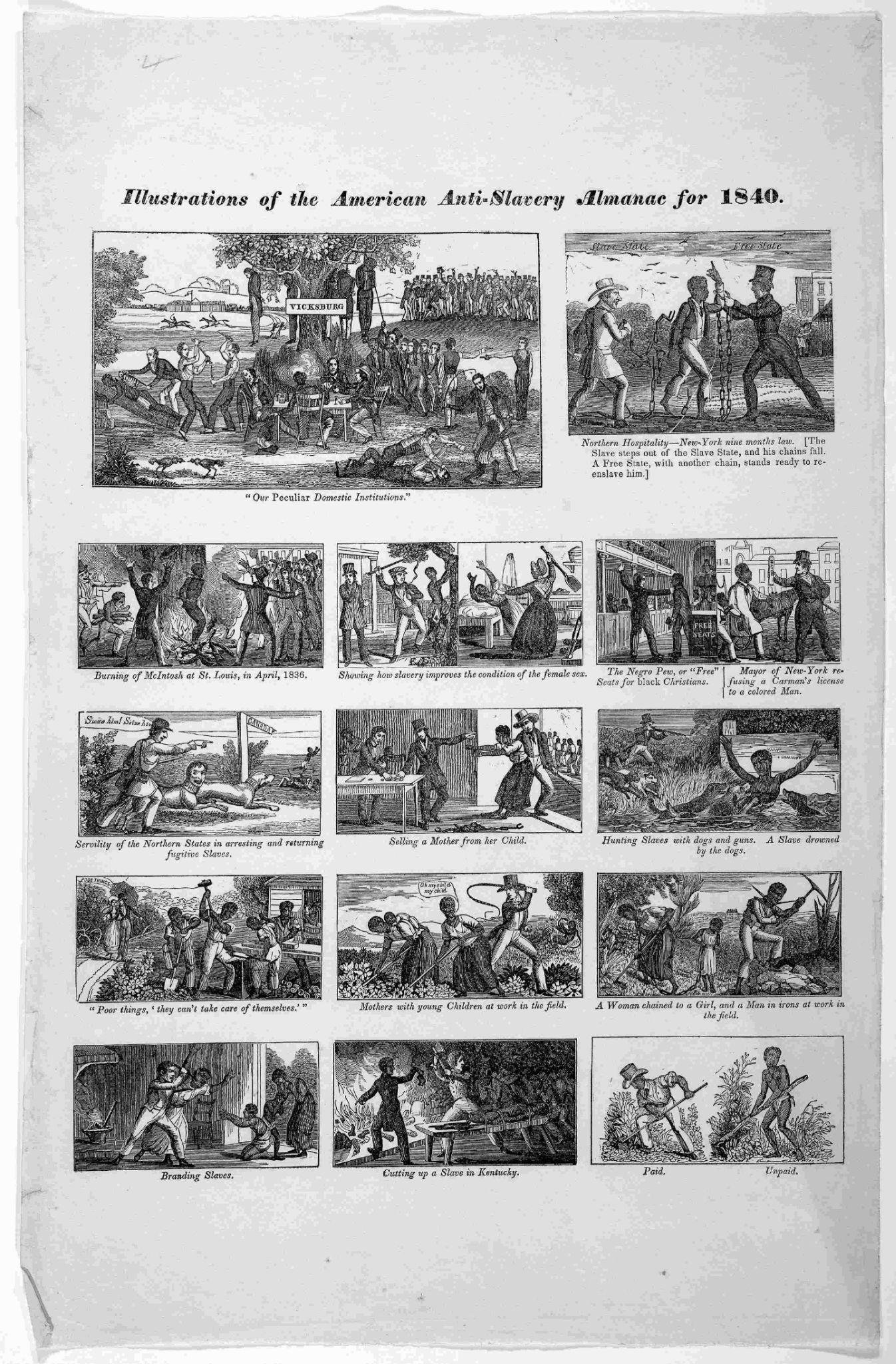

Similar to abolitionist writers, illustrators used Biblical references to support their argument, portraying white abolitionists as Christ-like savior figures, as seen in a popular Currier & Ives print depicting John Brown [Fig. 5].[7] In contrast, an illustrator chose to depict Nat Turner, a Black abolitionist, pejoratively barefoot and in torn clothing at the moment of his capture [Fig. 6].[8] Moreover, anti-slavery societies cavalierly sold almanacs as Christmas gifts at holiday fairs that depicted punishments inflicted upon the enslaved, auctions supporting their trafficking, and the separation of families [Fig. 7].[9] “Practical Illustration of the Fugitive Slave Law,” is particularly egregious [Fig. 8]. Here, Fredrick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison are shown standing side-by-side, holding pistols. The work further purports a caricature of Black woman fleeing human traffickers.

Figures from left to right:

Fig. 5. Currier & Ives. “John Brown Meeting the Slave Mother and Her Child on the Steps of Charleston Jail on His Way to Execution”, 1863. http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a06486/ (accessed May 25, 2022),

Fig. 6. “Discovery of Nat Turner”, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-a10b-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed May 25, 2022),

Fig. 7. American Anti-Slavery Society, “Illustrations of the American anti-slavery almanac for 1840,” (1840). Print. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.24800100/ (accessed May 25, 2022)

Fig. 8. Practical Illustration of the Fugitive Slave Law. Illustration. Boston, MA, 1851. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008661534/ (accessed May 25, 2022).

Conclusion

White abolitionists in the American Anti-Slavery Society and similar organizations worked tirelessly in support of the abolishment of enslavement in America. Surviving broadsides show their dedication to the cause, mixing established design with passionate writing and occasional imagery to capture and hold the reader’s attention. Yet, this passion cannot mask the way their message emphasized the superiority of its intended highly educated Northern white audience. Broadside authors employed language accessible only to those that were not only literate, but also had access to resources for further education, making biblical references that elevated white abolitionists to the position of saviors while belittling the South and discriminatingly delegating Blacks to a helpless and dependent class.

Endnotes

[1] Connor A. Scalise, “American Duality: The Legal History of Racial Slavery in the United States of America,” Dissertations and Honors Papers, 2020. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_student_papers/5 (accessed May 25, 2022).

[2] Dorothy Sterling, “Ahead of Her Time: Abby Kelley and the Politics of Antislavery,” (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1994).

[3] Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts sponsored the Compromise.. Webster’s other contribution to American politics include rebranding the English Separatists of Plymouth Colony as the Pilgrims to support his doctrine of “Manifest Destiny,” a belief that Euro-Americans were predestined by God to colonize North America, thereby enacting a genocide against Native Americans. PBS, “The Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act,” PBS: Africans in America (undated). https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2951.html (accessed May 25,2022)

[4] Paul J. Erickson, “Chapter 6: Readers and Writers,” in Industrial Revolution: People and Perspectives (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2008), 88-94.

[5] Outline of U.S. History, “The Second Great Awakening,” Anchor: A North Carolina History Online Resource (undated). https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/second-great-awakening (accessed May 25, 2022).

[6] Phillip Lapansky. “Graphic Discord: Abolitionist and Antiabolitionist Images” in The Abolitionist Sisters, edited by Jean Fagen Yellin and John C. Van Horne, 201-30 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994), 212; Library of Congress, “About this Collection,” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/ collections/broadsides-and-other-printed-ephemera/about-this-collection/ (accessed May 25, 2022).

[7] See fig. 5. Brown was executed after inciting a rebellion in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859. In the lithograph, Brown looks down at a Black woman and her child who are seated by his feet. Dignified even as he is led to execution, the image reinforces the notion that Brown was a martyr in the fight for freedom, a concept also portrayed in the poem, “John Brown’s Body” that states: “John Brown was John the Baptist of the Christ we are to see, / Christ who of the bondmen shall the Liberator be.” Plebs, “War Songs for the Army and the People, No. 2,” Chicago Daily Tribune, (December 16, 1861): 3. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84031490/1861-12-16/ed-1/ (accessed May 25, 2022).

[8] Turner was an enslaved Black preacher who led a rebellion in Virginia in 1831. “Discovery of Nat Turner”, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, the New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-a10b-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed May 25, 2022).

[9] Events such as the New England Christmas Boston Bazaar, hosted by the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society and the December Fair in Philadelphia connected the birth of Christ to the abolitionist movement and gave abolitionists the opportunity to raise money for their cause while distributing anti-slavery material. For the perspective of a free woman of color, see Kristen Hillaire Glasgow, “Charlotte Forten: Coming of Age as a Radical Teenage Abolitionist, 1854-1856” dissertation (Los Angeles, CA: University of California, Los Angeles, 2019). proquest.com/docview/2354422734 (accessed May 25, 2022).

Bibliography

The American Anti-Slavery Society. Illustrations of the American anti-slavery almanac for 1840. 1840. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.24800100/ (accessed May 25, 2022).

American Slavery. Moses Roper. October 8, 1839. Image. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-c9e4-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed May 25, 2022)

Call, J. W. Pocket Book Lost!! December 16, 1839. Image. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.01501900/ (accessed May 25, 2022)

Currier & Ives. “John Brown Meeting the Slave Mother and Her Child on the Steps of Charleston Jail on His Way to Execution”, 1863.

http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a06486/ (accessed May 25, 2022).

“Discovery of Nat Turner”, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-a10b-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed May 25, 2022).

Erickson, Paul J. “Chapter 6: Readers and Writers”. Industrial Revolution: People and Perspectives. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2008.

Glasgow, Kristen Hillaire. “Charlotte Forten: Coming of Age as a Radical Teenage Abolitionist, 1854-1856.” Dissertation. Los Angeles, CA: University of California, Los Angeles, 2019. proquest.com/docview/2354422734 (accessed May 25, 2022).

J. S. Potter & Co., printers. A Crusade against Slavery and Counterfeit Christianity. 1850. Image. https://digitalcollections.library.harvard.edu/catalog/990050995450203941 (accessed May 25, 2022).

Lapsansky, Phillip. “11 Graphic Discord: Abolitionist and Antiabolitionist Images.” In The Abolitionist Sisters, edited by Jean Fagen Yellin and John C. Van Horne, 201-30. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994.

Library of Congress. “About this Collection.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/ collections/broadsides-and-other-printed-ephemera/about-this-collection/ (accessed May 25, 2022).

Means, John, and R. E. Stanley. $2,500 Reward. August 23, 1852. Image. http://collections.mohistory.org/resource/216610 (accessed May 25, 2022).

Outline of U.S. History. “The Second Great Awakening.” Anchor: A North Carolina History Online Resource. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/second-great-awakening (accessed May 25, 2022).

PBS. “The Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act.” PBS: Africans in America. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2951.html (accessed May 25, 2022).

Plebs, “War Songs for the Army and the People, No. 2”, Chicago Daily Tribune. Chicago, December 16, 1861. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84031490/1861-12-16/ed-1/ (accessed May 25, 2022).

Practical Illustration of the Fugitive Slave Law. Illustration. Boston, MA, 1851. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008661534/ (accessed May 25, 2022).

Scalise, Connor A. “American Duality: The Legal History of Racial Slavery in the United States of America.” Dissertations and Honors Papers, 2020.

https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_student_papers/5 (accessed May 25, 2022).

Sterling, Dorothy. Ahead of Her Time: Abby Kelley and the Politics of Antislavery. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1994.