Abolitionist Broadsides and Anti-Slavery Imagery

In the early nineteenth century, broadsides were a common form of mass media, which were produced in bulk and intended for single use – as such, few nineteenth-century broadsides have survived. Those preserved in collections give historians an inside look at the ideology of anti-slavery societies and pro-slavery institutions, along with documenting design sensibilities and imagery of historical propaganda. Broadsides published by anti-slavery societies advocated for immediate abolition. Surviving broadsides show their dedication to the cause, mixing established design with passionate writing and occasional imagery to capture and hold the reader’s attention. Yet, this passion cannot mask the way their message emphasized the superiority of its intended highly educated Northern white audience.

Lost and Found: Anna Belle Mitchell, Jane Osti, and the “Revival” of Cherokee Pottery in Oklahoma

The tradition of Cherokee pottery is often denoted as a ‘lost’ art. Most documentation and scholarship about Cherokee potters problematize them as the last artists of their craft, and primarily focus on potters from the Southeast. Most of these scholarly viewpoints were from an anthropological or archeological perspective. Despite these narratives, Cherokee ceramicists in the Southeast have continued the allegedly lost tradition of pottery for generations. These misdirected narratives exclude how Cherokee pottery was indeed lost after the Cherokee removal and the Trail of Tears in the early 19th century for those displaced and sent to Indian Territory.

Not until the mid-1950s was Cherokee pottery revived in Oklahoma when Anna Belle Mitchell traveled to South Carolina and sought this traditional knowledge. Since her passing in 2012, Mitchell’s legacy and the continued art form of Cherokee pottery lives on in her pupil, JaneOsti. Osti has established a successful art career by utilizing and teaching Cherokee pottery techniques in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Explaining the significance of carrying on the Cherokee pottery tradition, Osti has stated, “Pottery is one of the greatest historians… I know that oral traditions are wonderful, but pottery can tell us the story of our people.” Preservation and practice of Cherokee pottery in Oklahoma by artists like Mitchell and Osti’s shows that the art form is resilient and ongoing rather than a revival or stagnant. This paper opens a discourse about the continuous misrepresentative pedagogy and specific wording, such as ‘lost’ or ‘revival’, that codes stasis narratives about Native American art in contemporary scholarship.

The Material Culture of the Sports Bra: Supporting Innovation and Femininity in Athletics

The invention of the sports bra by Lisa Lindahl, Hinda Miller, and Polly Palmer Smith in 1977 is a pivotal moment in women’s history: it not only influenced women’s stylistic choices in clothing, but also critically impacted their participation in athletics. These women were frustrated with the lack of support their regular brassieres offered for running and took it upon themselves to solve the issue. Lindahl’s husband pulled a jockstrap around his chest, and although this was intended as a joke, it inspired the first sports bra: the Jockbra (later renamed as the Jogbra), which resembled two jockstraps sewn together. As an object, the sports bra is able to inform the viewer about the culture surrounding it: of athleticism, femininity, technology, fashion, and business. A material culture analysis of the original Jogbra patent, fabric choices for sports bras, the evolution of the sports bra, advertisements, and the photograph of Branti Chastain’s victory in the 1999 Women’s Soccer World Cup will be utilized to understand how the sports bra impacts women’s broader experiences in society. Gender equality in athletics has been typically overlooked in academic scholarship and this paper intends to show the relevance of sports for women’s history through an analysis of the development of the sports bra. Although sports bras have been sexualized and presumed to be trivial by the media and general public because of their role as undergarments, the sports bra revolutionized women’s participation in athletics.

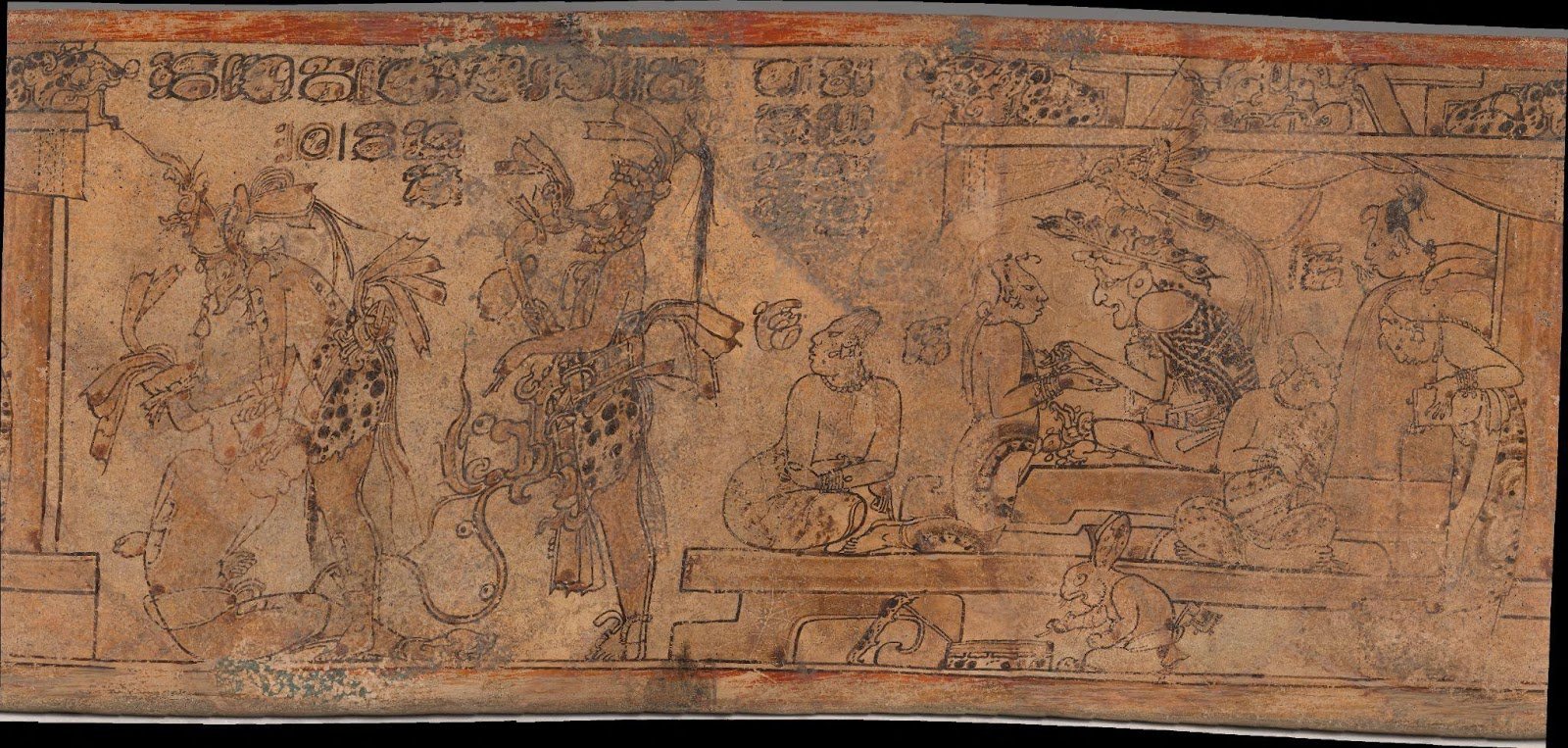

A Closer Look: Funerary Studies, Material Culture, and the Maya

The following analysis investigates literature from the field regarding a carbonate stone bowl, designated as “Bowl with Anthropomorphic Cacao Trees,” found in a tomb and located today in the collection of Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C. The three-roundel bowl is regarded to feature a personified Chocolate God as its central figure. On the other hand, some scholars in the field, including Simon Martin and Karl Taube, posit that the figure considered the “Chocolate God” on this funerary bowl is instead intended to represent the Maize God embodying the Chocolate God in a call for generational rebirth. The following seeks to offer an object biography under the lens of funerary studies and the material culture of the Maya. Visual analysis and study of Maya religious principles are also employed.

“Take me Back to the Good Old Days”: Racism, Berlin Wool Work, and Comfort

Whether they be hung, worn, or used in a multitude of ways, textiles are a tangible component of material culture. They can tell us anything from political culture to stories of nostalgia.This 1876 Berlin wool table cover found in the collection of Winterthur Museum (2020.004) is a curious example of how embroidery and nostalgia intersect. This piece of textile, while overtly racist in its presentations, actually helps us consider the idea of racism in textiles as a teaching object. Even though the imagery of this piece is highly racialized and offensive, it was also evidently loved and cared for by its owners—enough so that the owner, or owners, came back multiple times to make alterations and preserve the piece. This paper discusses not only the tangible aspects of the table cover such as the stitches and design influences, but also the intangible such as what the designs in the cloth tell an audience. Given that many of the designs on this tablecloth were taken from children’s stories, the piece argues that this was intentional in order to “other” Black bodies and garner a certain type of racism—nostalgic racism. This racism is presented in this object via the space of the parlor. The parlor was no longer just a place to be with family and on special occasions, but quickly became one of the most radical forms of conspicuous consumption of the nineteenth century. It was a space to make a statement about how your family perceives the world and vice versa. While this piece might stoke immediate negative feelings, it is critical to remember that those were not the feelings experienced by the owner of this piece and their family. They saw these racist images as amusing and a cultivator for conversation and community.

The Performativity of Hair in Victorian Mourning Jewellery

Mourning rings were popular items of remembrance in the Victorian era which commonly incorporated the hair of a departed loved one. The role of hair within this type of jewellery is discussed in relation to performativity; a theory that has been successfully employed by a variety of fields to better understand the nature and effects of certain kinds of performance, particularly those that closely relate to the expression and construction of identity. The form of mourning rings, the processes involved in their construction and the messages they communicated to society are examined in reference to performativity, to ascertain the value of considering the mourning ring tradition within this theoretical framework. This article asserts that the processes involved in the construction of mourning rings were not merely representational but performative, as they both symbolise and create transitions between conventional states. Moreover, mourning jewellery was an invented tradition within the larger culture of performative mourning, that addressed the need to reconstruct gendered class identities in the wake of profound social change.

Cultural Consumption, Colonialism, and Nationalism in an Egyptian Alabaster Scarab Beetle

Within a scarab beetle that was acquired during my travels in Egypt, one can read evidence of Egyptian history, both the European imperialist efforts as well as the Egyptian nationalist past, each often expressed through cultural consumption that continues even into today. Ultimately, my scarab beetle is a souvenir from my own travels in Egypt and thus is also taking part in this cultural consumption like so many other souvenirs. I argue that while my scarab beetle is representative of Egyptian culture, it is also part of this broader history of colonial consumption which then triggered the subsequent Egyptian response of manufacturing souvenirs for this demand. Eventually, modern Egyptians also came to foster nationalist sentiments and contest colonial rule, which then encouraged further consumption of Egyptian material culture, although from a place of nationalist pride. These nuances will be further examined throughout this paper, through the use of contemporary literature such as British news articles and short stories, as well as the Egyptian nationalist responses.

The KitchenAid:

First invented in 1908 for professional bakers, the KitchenAid was already being marketed to women for their homes by 1919, and within a few years had become a staple of prosperous suburban homes. The KitchenAid holds a surprising amount of meaning in the American mind. Over the years the KitchenAid has become a cultural symbol of prosperity, progression, idyllic suburbia, female duty, and family values. The history of the KitchenAid connects closely with a major shift that was occurring in America at the turn of the 20th century. Domestic servants were falling out of favor and suddenly affluent women were responsible for the domestic tasks in their homes. Tools like the KitchenAid made this possible, but also increased standards, and created a middle class ideal of home economics, an idea of a wife who is expert in her home duties. Kitchen appliances became a symbol of the American future, a new woman, and a new home. Paradoxically evoking ideas of both modernization and traditional domesticity, the KitchenAid maintains its multiplicity of meanings through its design. An unchanging aesthetic which balances beauty, functionality, and durability, has made the KitchenAid iconic, and has endowed it with a sentimentality that traverses generations, a sentimentality for the future its past users imagined.

Borat in the Age of Digital Inauthenticity

Parafiction, as coined by Carrie Lambert-Beatty in 2009, is fiction that intersects with lived experiences, and is “experienced as fact”. While Lambert-Beatty uses this lens to examine various performance art pieces, she mentions Sacha Baron Cohen as a cultural touchstone for her audience to understand her concept but does not analyse his work in any depth. The structure of this essay will use Borat and Borat Subsequent Moviefilm as both case studies and temporal bookends to look at the rise of parafictive works in digital spheres. When Borat came out in 2006, there was little in mainstream media that it could be compared to. With the release of Borat Subsequent Moviefilm in 2020, we are a culture inundated with parafictive works, and as such we experience the parafictive in a way that would not be possible in 2006.