The Material Culture of the Sports Bra: Supporting Innovation and Femininity in Athletics

Kathryn Pownall

Citation: Pownall, Kathryn. “The Material Culture of the Sports Bra: Supporting Innovation and Femininity in Athletics.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, December 17, 2021.

Abstract: The invention of the sports bra by Lisa Lindahl, Hinda Miller, and Polly Palmer Smith in 1977 is a pivotal moment in women’s history: it not only influenced women’s stylistic choices in clothing, but also critically impacted their participation in athletics. These women were frustrated with the lack of support their regular brassieres offered for running and took it upon themselves to solve the issue. Lindahl’s husband pulled a jockstrap around his chest, and although this was intended as a joke, it inspired the first sports bra: the Jockbra (later renamed as the Jogbra), which resembled two jockstraps sewn together. As an object, the sports bra is able to inform the viewer about the culture surrounding it: of athleticism, femininity, technology, fashion, and business. A material culture analysis of the original Jogbra patent, fabric choices for sports bras, the evolution of the sports bra, advertisements, and the photograph of Branti Chastain’s victory in the 1999 Women’s Soccer World Cup will be utilized to understand how the sports bra impacts women’s broader experiences in society. Gender equality in athletics has been typically overlooked in academic scholarship and this paper intends to show the relevance of sports for women’s history through an analysis of the development of the sports bra. Although sports bras have been sexualized and presumed to be trivial by the media and general public because of their role as undergarments, the sports bra revolutionized women’s participation in athletics.

Keywords: women’s history, Title IX, sports bra, fashion history, athletic history

The 1977 invention of the sports bra by Lisa Lindahl, Hinda Miller, and Polly Palmer Smith not only influenced women’s clothing choices, but also critically impacted women’s participation in sports. It importantly demonstrated a move away from women’s brassieres being made by men and based on societal ideals, to the creation of functional garment designed by women to solve practical problems in athletics. The sports bra creation and evolution can instruct the viewer about the culture of the 20th century because it is located at the intersection of athleticism, femininity, technology, fashion, and business. Paul R. Joseph argues that the sports bra is an important technological accomplishment, and as a result, historians cannot look at it “in isolation, but must consider the messy interaction of engineering, scientific, financial, governmental, consumer, and social institutions in giving impetus – or creating obstacles” to the distribution of the sports bra in American culture.[1]

This article is a material culture analysis of the sports bra that will be completed through an examination of the design structure, physical object, and material fabrics used in the creation of the first sports bra, the Jogbra. Additionally, an examination of advertisements produced by Jogbra Inc. will illustrate how these campaigns were practical and women-centered, unlike other advertisements which preyed on women’s anxieties about their femininity and athleticism. The analysis will expand to demonstrate how important events in women’s athletics were impacted by the invention of the sports bra, such as the passing of Title IX in 1972 and the Women’s Soccer World Cup Final in 1999. Although sports bras have been sexualized and presumed to be trivial by the media and the public because of their role as undergarments, the sports bra ultimately revolutionized women’s participation in athletics.

Incorporating a material culture perspective into studies of history is vital as it illustrates cultural change “through its capacity to embody symbolic values,” as well as reinforce those values in the consumer.[2] The choice to acquire, use, or discard an item can demonstrate the consumer’s values. Clothing, in particular, is a fascinating facet of material culture studies. Diana Crane and Laura Bovone argue that clothing functions as a “vehicle for socialization and social control or, alternatively, for liberation from cultural constraints.”[3] The choices one makes in what they wear symbolizes the culture that surrounds them, by either demonstrating how they were socialized to make these choices or how they use fashion to reject popular trends. Additionally, the choices made by individuals on what clothing to wear “both affect and express our perceptions of ourselves.”[4] Because of their association with a sense of self, clothing can reveal to historians the personal values of individuals within a society.

Societal expectations may have characterized the sports bra as a trivial piece of clothing, yet it can demonstrate women’s complex experience of society. In Clothing as Material Culture, Daniel Miller argues that because clothing can be perceived as a simplistic covering of another object, it can be “easily characterized as intrinsically superficial.”[5] Undergarments, like brassieres and sports bras, are further characterized as trivial because they are often hidden from view, underneath other layers of clothing. However, if one explores the literature about the history of brassieres, it is clear that feminine undergarments are vital to studying women’s history.[6] Jane Farrell-Beck and Colleen Gau argue in Uplift: The Bra in America, that brassieres can reveal history through demonstrating how women’s social status has changed: “underclothes have been modified in accordance with changing fashions, hygienic concepts, textile production, manufacturing techniques, and commercial distribution.”[7] Scholars have often characterized brassieres as objects of seduction, glamour, and oppression, which can make their research lose “sight of the key people and events in the development of the brassiere as a material and social artifact.”[8] However, the three women who invented the sports bra took control of their own athletic endeavors which allowed the object to be studied as an artifact of revolution rather than seduction or oppression.

Brassieres historically lacked support for female athletes. Hinda Miller, one of the three inventors of the sports bra, emphasized how physically uncomfortable regular bras were for physical activity, “Our breasts jiggled uncomfortably when we ran. Our nipples became sore from chafing against our sweaty t-shirts.”[9] Women’s breasts made athletic activity physically painful because breasts are “sacks of fat and connective tissue that move independently from the rest of the body, with no muscle or bone to halt motion.”[10] If a woman wears nothing or just a regular bra, their breasts will bounce and cause genuine pain. Jaime Schultz details how women attempted to solve this issue and reduce the motion in breasts during physical activity. This action dates back to Ancient Greece where the Amazons were rumored to have cut off their right breast in order to improve their skills in archery. Similarly, Violette Gouriand-Morris, a French athlete, chose to have a double mastectomy in 1929 because she felt her breasts impeded her ability to control the steering wheel of her racing car.[11] These extreme measures were not typical, but breasts were often bound by women with cloth or leather to minimize movement. In 1966, Roberta (Bobbi) Gibb ran the Boston Marathon and wore a tank top bathing suit because she felt she had no other option.[12] As these examples show, the lack of a bra that was specifically designed for athletic activity caused women to take matters into their own hands, sometimes in drastic manners.

An increased interest in running swept the United States in the 1970s, changing the athletic endeavor from an activity that was only in the domain of competitive athletes to a hobby of the general public.[13] In the 1970s, the country was also in the midst of the second wave of feminism and as a result, “the running boom created new avenues for women to enhance and build up their community solidarity.”[14] There was no training required to be a runner; therefore, running became a social activity that groups of women could participate in together easily. In 1977, Lisa Lindahl was a serious runner who was frustrated by the lack of support her regular bra offered. Lindahl was a graduate student at the University of Vermont and to brainstorm a solution to her dilemma she approached her childhood friend, Polly Smith, who worked as a costume designer. Smith invited Hinda Miller, who was working that summer as her assistant costume designer, to the project.[15] Together, the three women were determined to solve the issues that ordinary brassieres caused during physical activity.

The inspiration for the sports bra emerged as a joke. Lindahl’s husband interrupted one of their brainstorming meetings and pulled a jockstrap over his head and around his chest.[16] Although he simply meant to make the group laugh, the three women were inspired by the utility of jockstraps for male athletes and applied its concept for female athletes. Miller stated, “what we really need to do is what men have been doing: pull everything close to the body.”[17] The first sports bra resembled the look of two jockstraps sewn together.[18] The oval pouches of the jockstrap became the front of the bra, the waistband became the elastic around the torso, and the leg straps became the shoulder straps.[19] To avoid discomfort, all the seams were placed on the outside.[20] This would eliminate the straps rubbing against the wearer which would otherwise result in chafing the skin. Lindahl, Miller, and Smith originally named this contraption the “Jockbra” in honor of the inspiration, but eventually the name became “Jogbra.”[21]

Jogbra Inc. was founded in 1977. It became the first women-owned sporting goods business in the United States.[22] Although the three inventors had little business experience prior to this endeavor, they persisted. The patent for the product was received on November 20, 1979, and the trademark for the brand was obtained on August 17, 1982. Jogbra Inc. utilized important research that allowed them to create comfortable and lightweight bras that were also supportive of physical activity.[23] The important fabrics that were employed to achieve this goal were cotton, polyester, and Lyrca, which provided comfort, strength, and support.[24] The patent describes the distinct design of their innovative product, which they identified as “the first athletic supporter for women.”[25] The goal of the product was to keep the athlete’s breasts held firmly against her body to diminish movement and increase comfort. Additionally, the Jogbra supported athletic activity through its sweat-absorbing fabric and straps that did not slide off the shoulder, no matter how forceful the athletic activity the wearer engaged in. A unique feature of Jogbra’s design was that it involved no hardware, such as clasps and hooks, that would have decreased comfort for the user.[26] Instead, the product prioritized securing the breasts through material and structure choices. The support for the chest in a sports bra comes from four main points in the structure: the elastic shoulder straps, the cups, the elastic chest band, and the wings.[27] Overall, Lindahl, Miller, and Smith stated that the Jogbra’s “main uniqueness is its ability to ‘bind’ – to hold the breasts firmly against the body – while remaining comfortable and lightweight.” [28] As a result of this unique design, the patent was approved and their idea for the invention was protected.

Figures 1 and 2: Front and back view of the Jogbra along with its original packaging. Science History Institute, Jogbra, photograph, Science History Institute, Philadelphia, https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/np193950z.

An important characteristic of the sports bra is that it was created by women, for women. Josephson argued that “unlike the first bra which had been a male fantasy of the female body with form coming before function,” the sports bra prioritized function over all other qualities.[29] Brassieres had developed to “emphasize curves and breast size” because of this historical prioritization of aesthetic form over comfort.[30] Lindahl, Miller, and Smith did not invent the sports bra with the desirability of men in mind. In fact, Lindahl was quoted to have said it was not attractive at all, “but I didn’t care. And the women who were buying it didn’t care.”[31] Women were simply excited to have the opportunity to run without worrying about pulling their bra straps up for support and to avoid terrible comments from men about their breasts when they ran down the street. Johnson argues that technology which has been created for women has typically been male-dominant in its development, which can create “barriers to safer devices and appropriate technologies.”[32] The birth control pill is an illustrative example of how technology that was developed by men was detrimental to women’s experiences with the product. Science and technology have historically privileged men, making “the woman the invisible ‘other.’”[33] The development of the sports bra departed from this male-dominated narrative because women produced the technology themselves, solving issues of discomfort and support they had experienced first-hand.

Changes in the material of intimate apparel, more generally, demonstrate women’s overarching concern of having durable athletic garments. Winnie Scherer emphasizes the intrinsic and extrinsic features of material when women purchase undergarments in Advances in Women’s Intimate Apparel Technology. Intrinsic features concern the functional properties of the fabric and extrinsic features include the price of the object and the brand which manufactured it.[34] The versatility in the material properties of brasseries is important because the objects need to “have easy-care properties, be lightweight, be comfortable, provide freedom of movement, be durable, and even have antibacterial or anti-odor properties.”[35] Companies that manufacture materials that have been employed for these uses include Nylstar, Invista, Toray, and Lenzing. Cotton was used for undergarments because it retained moisture to maintain body heat. Sweat, however, cannot quickly evaporate from the fabric which can make the wearer uncomfortable. If sweat is unable to escape, it can linger on the skin making the wearer feel sticky. Synthetic fibers emerged to combat these problems. They have dry-fit functions that expel perspiration quickly from the fabric when it comes into contact with skin.[36] The emerging variations in brassiere material demonstrated a focus on athletic wear, which allowed for companies like Jogbra Inc. to focus their innovation on the design.

Over time, Jogbra Inc. began to introduce new iterations to their initial sports bra. The company asserted that it had the “important belief that no matter what the woman’s age or shape, she had the right to the benefit of exercise.”[37] A sports top was developed by Jogbra Inc. quickly after the sports bra because they understood that not all women wanted to show off their abdomen. Additionally, they wanted to create aesthetically pleasing sports bras because they knew that some users would want to remove their shirt and just wear the sports bra. Color became an important extrinsic quality of the sports bra and as a result Jogbra Inc. quickly introduced spring, summer and fall designs for consumers.[38] Additionally, more women were exercising which raised demand for the sports bra. As a result of the company’s success, Playtex Apparel purchased Jogbra Inc. in 1990. A year later, Sara Lee Corporation bought Playtex and Jogbra Inc. was subsumed by Champion Sportswear.[39] Other companies were inspired by the revolution the Jogbra brought to the athletic industry and followed suit with their own designs for sports bras. Nike introduced its first women’s athletic wear line, which included sports tops, in 1979.[40] The company continued to revolutionize the sports bra and began studying breast motion in female athletes in the Nike Sports Research Lab during the 1990s.[41] Their research led to the first compression sports bra in 1999 and a no-seams bra called the Nike Revolutionary Support in 2006. The Nike Revolutionary Support sports bra introduced encapsulation to sports bras. Instead of compressing the breasts to the chest, encapsulation lifted and supported the breasts because it was built to meet the size and shape of the breast.[42] The evolution of the sports bra demonstrates how it was a groundbreaking invention in athletics that gave women the ability to increase their comfort while exercising. Additionally, variations in sports bra design provided an opportunity for women to incorporate stylistic preferences in clothing in a new way that merged function and aesthetics.

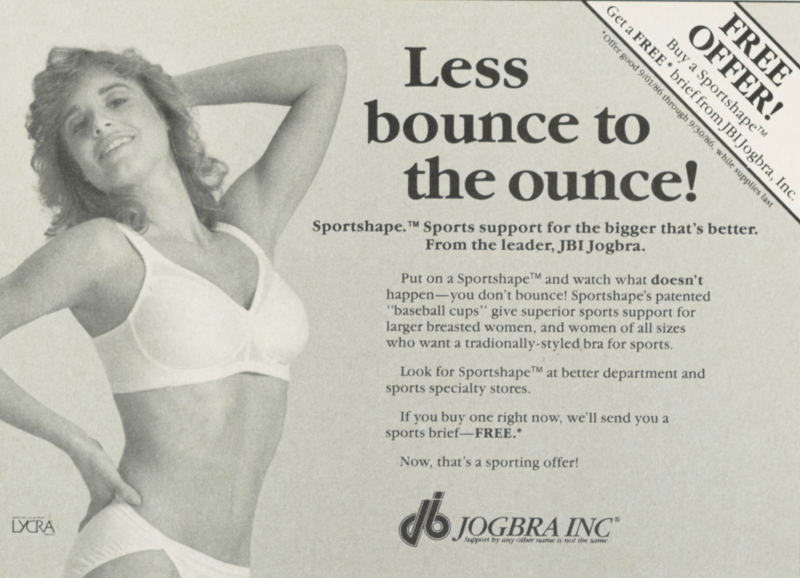

Advertisements are key aspects of material culture studies. Advertisements can be distributed through magazines, catalogues, and television programs which “disseminate images of clothing more widely than the products they depict.”[43] The public is more likely to see an advertisement for a sports bra than see someone wear one, especially because sports bras are typically hidden beneath other layers of clothing. Additionally, brands can “transmit sets of values that imply an ideology and specific lifestyles” through their advertisements, demonstrating what they want the public to perceive about their product.[44] Jogbra Inc. advertisements for their sports bras often depicted personal values of health and physical activity. A tagline from Jogbra Inc. promotional material asserted that “no man-made sporting bra can touch it,” which emphasized how the Jogbra is a women-centered product created by women. [45] Jogbra Inc. centered their advertisements around women’s experiences; they explained how the seams prevent chafing and cut away from nipples to avoid irritation, and how the shoulder straps ensure there is “no more hunching your shoulders to hold up your sports bra.”[46] Jogbra Inc. advertisements also focused on inclusivity. As illustrated in Figure 3, the Sportshape bra was designed for “larger breasted women, and women of all sizes.”[47] Separating from the original sports bra design, the Sportshape had a baseball cup design similar to a traditional bra that was stated to have “less bounce to the ounce!” for women with larger breasts who may have been uncomfortable with the tight support of a traditional sports bra.[48] Another advertisement created by Jogbra Inc. depicted co-inventors Hinda Schreiber and Lisa Lindahl on a run wearing their Jogbras. It aimed to invite all women to join in their run with the tagline: “Get ready for a run with Jogbra!” [49] Overall, the advertisements created and disseminated by Jogbra Inc. focused on demonstrating the product’s functionality and practicality. These advertisements also established that the sports bra was created to be inclusive of all women, no matter their size, athletic ability, or aesthetic preferences. The sports bra became vital to society because of its functionality to all women. This pragmatic approach to advertising showed how the Jogbra improved upon previous brassieres in a way that made physical activity more accessible for women.

Figure 3: Advertisement for Jogbra, Inc.’s Sportshape sports bra that featured in Cosmopolitan magazine in 1986. Jogbra, Inc. “Less Bounce to the Ounce!,” 1986, advertisement, Science History Institute, Philadelphia, https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/qn59q408f.

Not all advertisements for sports bras empowered their audience. Schulz analyzed an advertisement for Champion’s “New Shape 2000 Bra,” a new sports bra that was created with a “unique cup design that eliminates ‘uniboob’ by delivering comfortable support with the most natural shape and definition possible.”[50] A uniboob is when a woman’s breasts are compressed together and flattened to the chest, which gives the appearance of a singular, undifferentiated breast. A uniboob contrasts with what is socially desired, a full and round set of breasts. Champion attempted to heighten anxiety in women over the possibility of having a uniboob in order to increase the sales of their new sports bra design. This advertisement by Champion escalates women’s existing insecurities over their bodies. This increased body insecurity could negatively impact female participation in athletics. While the original Jogbra Inc. advertisements appealed to female athleticism and promoted the sports bra as a functional tool to make exercise more accessible and enjoyable, the later Champion advertisements attempted to make the consumers insecure over their bodies by introducing worries over a uniboob. The first sports bra was created to solve the issues women felt while participating in sports and this message was communicated clearly through their advertisements. Champion’s advertisement exploited and created new anxieties for women by making the sports bra less about function and more about how the sports bra could give women the bodily aesthetics that align with societal ideals.

The introduction of the commercial sports bra by Jogbra Inc. had a vital impact on the participation of women in sports. Miller, co-inventor of the Jogbra, was quoted to have said, “sports bras now generates $500 million at retail and is recognized as having as big a role as Title IX in increasing women’s participation in sports and fitness.”[51] Title IX of the Education Amendments was passed in 1972, which states, “no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”[52] Educational issues that fall under Title IX include recruitment, admissions, financial assistance, athletics, treatment of pregnant students, and sex-based harassment. Title IX applies to any institution that receives funding from the federal education department, which currently includes 16,500 school districts, 7,000 universities and colleges, as well as libraries and museums.[53] The scope of Title IX is far and wide. It is clear that Title IX had important consequences on women’s participation in athletics over the years after its implementation. In 1996, which was close to the twenty-five-year anniversary of Title IX, there was an eightfold increase in girls’ participation in high school athletics with 2.4 million girls participating. Additionally, women’s participation in collegiate sports increased by 400 percent in the twenty-five-year period.[54] However, compared to men’s participation rates, women still were behind in 1996: 39 percent of high school athletes and 37 percent of collegiate athletes were women.[55]

The number of women as key officials in sports has decreased inversely to the increase in participation. Schulz argues that there is an “inversely proportional relationship between women’s gains in participation and their roles as key functionaries.”[56] In 1972 when Title IX was passed, women made up more than 90 percent of administrators for women’s sports programs, but by 2000 it was an all-time low of 17.4 percent.[57] Women’s roles as coaches for women’s teams also reached an all-time low in 2000, with 45.6 percent female coaches compared to the above 90 percent in 1972.[58] These numbers come from a longitudinal study of intercollegiate sports produced by R. Vivian Acosta and Linda Jean Carpenter and funded by Brooklyn College of CUNY and the Smith College’s Project on Women and Social Change. Data was collected through mailed questionnaires to Senior Women Administrators at NCAA schools. An updated report was published in 2014, with thirty-seven years of data. Since the 2000 report, there were improvements in the athletics job market for women. There was the highest ever number of assistant coaching and athletic training employment opportunities for women at this time.[59] Although women were given more chances to participate in coaching, they were still not respected in the eyes of men who dominated the sports industry. Women are not given the opportunity to coach ‘respected’ men’s programs. In the 2014 report, it states that 2 to 2.5 percent of men’s programs were coached by women, which is a negligible increase from 1972.[60]

The lack of women coaches for men’s teams and the decreasing numbers of women coaches for women’s teams may demonstrate the respectability that Title IX brought to women’s athletics. If women’s sports programs were to be better established and funded, men were brought in as key functionaries instead of women. Despite key improvement because of Title IX in student and collegiate participation, “women continued to suffer from lack of opportunity, compensation, and exposure in the sports-media-commercial complex.”[61] Though rates were still significantly lower than men’s, Title IX had an undeniable and positive impact on women’s participation in athletics. As a result, these new women athletes created a new demand for sports equipment to fit their needs and the sports bra helped meet and grow this need.

The 1999 Women’s Soccer World Cup was another key event that emphasized the importance and controversial nature of the sports bra for female athletes. Schulz argued that “even in the face of such widespread promotion and popularity, one could argue it was the 1999 World Cup that served as the sports bra’s coming out party.”[62] The championship match between the United States and China was tied after “120 minutes of spectacular scoreless action” and became a penalty shoot-out to determine the world champions.[63] After nine women from both teams evened the score to 4-4, Brandi Chastain on Team USA clinched victory for the United States team.[64] In a moment of pure joy, Chastain stripped off her jersey and raised her fists in victory. This exposed her sports bra to all the spectators in the arena, as well as the rest of the world through distributed images in the media. This moment of celebration not only captured the attention of the American public in real-time because of their victory, but it was also immortalized for various conflicting reasons. Sports Illustrated editor William Colson described the image as “the greatest picture of a sports bra in the history of publishing,” praising the photo for the attention it caused in regard to her clothing and body, rather than the athletic achievement it should represent.[65] In the media, the moment was described as a “striptease,” a “provocative gesture,” and “the most brazen bra display this side of Madonna.”[66] These descriptions suggest that a portion of the American public believed that she had the “deliberate intention of titillating onlookers” through removing her jersey, instead of viewing it as a moment of pure joy.[67] Schulz argues that the sexualization of Chastain’s celebration suggests that “the promise of bodily displays made women’s athletics enticing to otherwise uninterested sports fans.”[68] Chastain’s celebration drew the attention of the public because of the presumed inherent sexuality embodied in a woman wearing a sports bra and not because of the feat of athletic achievement she just accomplished. Even though the sports bra was created as a practical solution to discomfort in athletics, society found a way to sensationalize women’s bodies through the sports bra. Women’s participation, although increasing, continued to be trivialized in the perception of the public.

Chastain’s moment of celebration was not unprecedented because male athletes often remove their shirts in celebration of victory. The practice of removing one’s shirt following victory is most prominent in soccer, so Chastain’s action should not have been perceived as out of the ordinary for the sport. She was wearing a bra and was not exposing her bare breasts to the public, yet she was discriminated against for the same action done by men simply because she was a woman. Schulz argues that the discrimination was not a result of “whether female athletes should have the same public disrobing rights as male athletes, but, rather, what is made of those athletes once their tops come off.”[69] Men’s celebrations of victory were perceived as pure celebrations, but women’s celebrations were sexualized because of their bodies being on display.

The reactions to Chastain’s moment of celebration, therefore, illustrate societal issues between femininity and athletics. Schulz argues that Chastain demonstrates the tensions between women’s advancement in sports and how the rest of society attempted to keep their advancements in check.[70] There were conflicting representations of Chastain and her celebration in the media, where she was framed as either a “triumphant athlete,” the “poster girl for the success of Title IX,” the model of “changing feminine ideals,” a “corporate shill,” or a “scheming opportunist.”[71] The public struggled in their interpretations of this moment and what it meant for a woman to display herself only in a sports bra. The American public could not simply acknowledge Chastain’s achievements as an athlete without also drawing attention to her existence as a sexualized being. This sexualization occurred even though the sports bra was created by women to ease their discomfort in athletic activity. Schulz argues that this moment emphasized “notions of women’s sexual difference and positioned their bodies as sexualized objects” in the media and during athletics.[72] Despite these diverse reactions, Chastain’s celebration following her achievement at the World Cup was still a moment that gave female athletes empowerment and autonomy in their femininity.

The use of the sports bra has changed throughout time and during the 1990s it became acceptable to wear the sports bra alone. This growing acceptability of the sports bra as outerwear is attributed to Chastain’s celebration. Mike May, from the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association, stated that Chastain “made it okay for women to wear sports bras without anything else on top.”[73] The sports bra, therefore, can serve a multitude of purposes. It can be a piece of sports equipment, a type of lingerie, and a subversive fashion statement. The sports bra worn alone became a symbol of agency in the new millennium, as it was a “disavowal of traditional prudery that consigned the brassiere to underwear and a public declaration” of one’s identity as an athlete or ‘workout woman.’[74] Wearing a sports bra alone was a public statement that a woman had control over her own body, and it was an attempt to push back against how the sports bra was perceived by the public. Over time, women’s sports garments have become increasingly normalized and entrenched in society. This can be seen in modern fashion. The current athleisure trend in the United States where women wear athletic clothes for leisure activities has added a new trendiness to the sports bra. This increase in consumption, where some women wear sports bras as everyday apparel, has expanded innovation in the design of sports bras. As a result, more clothing and athletic companies see the utility in offering sports bras options to their consumers. The widespread popularity of sports bras has allowed technological developments from high-end athletic brands to trickle down to affordable brands so that women can buy their sports bras at companies like Target.[75]

In conclusion, there have been many contributions to the perception of the modern-day sports bra. The running craze of the 1970s and Title IX both helped increase female participation in sports and, as a result, there was a greater societal need for women’s options in athletic brassieres. The response to Brandi Chastain’s celebration at the 1999 Women’s World Cup demonstrated how public perception has inherently sexualized the sports bra, but the modern athleisure fashion trend currently reveals how women push back against societal assumptions by using the functional sports bra as an aesthetic fashion choice. Although the original Jogbra Inc. prototype initially began as a joke of using jockstraps for female issues, many other companies saw the opportunity for consumers and were inspired to create sports bras with innovative features like no-sew and encapsulation. The sports bra was initially a product designed by women, for women; it was a functional piece of material culture that solved issues women had historically experienced in sports and helped to increase women’s athletic participation.

This initial aim of the sports bra is clearly reflected in the advertising centered around women’s experiences and inclusivity. However, as the sports bra became more popular, advertising goals changed and preyed on women as consumers by using their vulnerability and insecurities to sell their product. As the sports bra became widespread in society, its original intention to uplift women was co-opted to increase sales through new marketing tactics. Despite changes in the physical design of sports bras that increased function and comfort, the continued trivialization of female athleticism persisted. Moments like Chastain stripping off her jersey to expose her sports bra while celebrating a World Championship demonstrate how women are deeply sexualized in American culture, even in their athletic pursuits. Although women in 2021 have attempted to fight back against this sexualization through wearing sports bras alone as part of the athleisure movement, there is still a long way to go. Despite these longstanding issues of trivialization and sexualization of women in sports, the sports bra fundamentally reshaped how women could participate in athletics by making them feel welcome in pursuing sports, as well as improving their comfort overall while participating.

Endnotes

[1] Paul R. Josephson, Fish Sticks, Sports Bras, and Aluminum Cans: The Politics of Everyday Technologies, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015), 4.

[2] Diana Crane and Laura Bovone, “Approaches to Material Culture: The Sociology of Fashion and Clothing.” Poetics (Amsterdam) 34, no. 6 (2006), 320.

[3] Crane and Bovone 2006, 320.

[4] Crane and Bovone 2006, 321.

[5] Daniel Miller, “Introduction,” in Clothing as Material Culture, ed. Susanne Küchler and Daniel Miller, (Oxford, UK: Berg, 2005), 2-3.

[6] See also important scholarship on the history of brassiere: Jane Farrell-Beck and Colleen Gau, Uplift: The Bra in America, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002); Wendy A. Burns-Ardolino, Jiggle: (re)shaping American Women, (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2007); Béatrice Fontanel, Support and Seduction: The History of Corsets and Bras, (New York, N.Y: Abrams, 1997); and Amber J. Keyser, Underneath It All: a History of Women’s Underwear, (Minneapolis: Twenty-First Century Books, 2018).

[7] Jaime Schultz, “A Cultural History of the Sports Bra,” in Qualifying Times: Points of Change in U.S. Women's Sport, (University of Illinois Press, 2014), 151.

[8] Jane Farrell-Beck and Colleen Gau, Uplift: The Bra in America, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), xi

[9] Josephson 2015, 34.

[10] Ariella Gintzler, “We’re in the Middle of a Sports-Bra Revolution,” Outside Magazine, March 5, 2020, https://www.outsideonline.com/2409754/sports-bra-design-revolution.

[11] Schultz 2014, 151.

[12] Schultz 2014, 152. Bobbi Gibb ran the Boston Marathon unofficially in 1966 because women were not permitted to race until 1972.

[13] Aaron L. Haberman, “Thousands of Solitary Runners Come Together: Individualism and Communitarianism in the 1970s Running Boom,” Journal of Sport History 44, no. 1 (2017), 36.

[14] Haberman 2017, 44

[15] Josephson 2015, 33.

[16] Josephson 2015, 34.

[17] Schulz 2014, 152.

[18] The cross-strap design persists in sports bra to this day, as a result.

[19] Schultz 2014, 152.

[20] Josephson 2015, 34.

[21] Schultz 2014, 152

[22] Lauren Emanuel, “Establishing the New Fit,” United States Patent and Trademark Office, https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/journeys-innovation/field-stories/establishing-new-fit.

[23] Josephson 2015, 6.

[24] Josephson 2015, 35.

[25] “Jogbra, Inc. Records,” National Museum of American History.

[26] “Jogbra, Inc. Records,” National Museum of American History.

[27] Josephson 2015, 40.

[28] “Jogbra, Inc. Records,” National Museum of American History.

[29] Josephson 2015, 34.

[30] Josephson 2015, 34.

[31] Gintzler 2020, “We’re in the Middle of a Sports-Bra Revolution.”

[32] Josephson 2015, 44.

[33] Josephson 2015, 35.

[34] Winnie Sherer, Advances in Women’s Intimate Apparel Technology, (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Woodhead Publishing, 2016), 37.

[35] Scherer 2016, 3.

[36] Scherer 2016, 7.

[37] Josephson 2015, 38.

[38] Josephson 2015, 38.

[39] Allison Keyes, “How the First Sports Bra Got Its Stabilizing Start,” Smithsonian Magazine, March 18, 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-first-sports-bra-got-stabilizing-start-180974427//.

[40] Josephson 2015, 39.

[41] Josephson 2015, 39.

[42] Josephson 2015, 39.

[43] Crane and Bovone 2006, 322.

[44] Crane and Bovone 2006, 322.

[45] “Promotional Literature,” Collections, National Museum of American History https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/NMAH.AC.1315_ref173.

[46] “Promotional Literature,” National Museum of American History.

[47] Jogbra, Inc. “Less Bounce to the Ounce!,” 1986, advertisement, Science History Institute, Philadelphia, https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/qn59q408f.

[48] Jogbra, Inc. “Less Bounce to the Ounce!”

[49] “Promotional Literature,” National Museum of American History.

[50] Schultz 2014, 160.

[51] Josephson, Fish Sticks, Sports Bras, and Aluminum Cans, 55.

[52] “Title IX and Sex Discrimination,” United States Department of Education, https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/tix_dis.html.

[53] “Title IX and Sex Discrimination.”

[54] Schultz 2014, 155.

[55] Schultz 2014, 155.

[56] Schultz 2014,155.

[57] R. Vivian Acosta and Linda Jean Carpenter, “Women in Intercollegiate Sport: A Longitudinal Study (2000),” 9.

[58] Acosta and Carpenter, “Women in Intercollegiate Sport (2000),” 5.

[59] R. Vivian Acosta and Linda Jean Carpenter, “Women in Intercollegiate Sport: A Longitudinal Study (2014),” B and C.

[60] Acosta and Carpenter, “Women in Intercollegiate Sport (2014),” A.

[61] Schultz 2014, 155.

[62] Schultz 2014, 154.

[63] Schultz 2014, 149.

[64] Schultz 2014, 149.

[65] Schultz 2014, 166.

[66] Schultz 2014, 158.

[67] Schultz 2014, 158.

[68] Schultz 2014, 158.

[69] Schultz 2014, 157.

[70] Schultz 2014, 157.

[71] Schultz 2014, 157.

[72] Schultz 2014, 150.

[73] Schultz 2014, 158.

[74] Schultz 2014, 158.

[75] Gintzler 2020, “We’re in the Middle of a Sports-Bra Revolution.”

Bibliography

Acosta, R. Vivian and Linda Jean Carpenter. “Women in Intercollegiate Sport: A Longitudinal Study—Twenty-Three Year Update, 1977-2000.” https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED446029.pdf.

Acosta, R. Vivian and Linda Jean Carpenter. “Women in Intercollegiate Sport: A Longitudinal Study—Thirty-Seven Year Update, 1977-2014.” http://www.acostacarpenter.org/2014%20Status%20of%20Women%20in%20Intercollegi ate%20 Sport%20-37%20Year%20Update%20-%201977-2014%20.pdf

Cooky, Cheryl and Michael A. Messner. "Women, Sports, and Activism." In No Slam Dunk: Gender, Sport, and the Unevenness of Social Change, 70-90. New Brunswick; Camden; Newark; New Jersey; London: Rutgers University Press, 2018.

Crane, Diana, and Laura Bovone. “Approaches to Material Culture: The Sociology of Fashion and Clothing.” Poetics (Amsterdam) 34, no. 6 (2006): 319–333.

Emanuel, Lauren. “Establishing the New Fit.” United States Patent and Trademark Office. https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/journeys-innovation/fieldstories/establishing-new-fit (accessed April 30, 2021).

Farrell-Beck, Jane, and Colleen Gau. Uplift: The Bra in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

Gintzler, Ariella. “We’re in the Middle of a Sports-Bra Revolution.” Outside Magazine. March 5, 2020. https://www.outsideonline.com/2409754/sports-bra-design-revolution.

Haberman, Aaron L. "Thousands of Solitary Runners Come Together: Individualism and Communitarianism in the 1970s Running Boom." Journal of Sport History 44, no. 1 (2017): 35-49.

Josephson, Paul R. Fish Sticks, Sports Bras, and Aluminum Cans: The Politics of Everyday Technologies. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015.

Allison Keyes. “How the First Sports Bra Got Its Stabilizing Start.” Smithsonian Magazine, March 18, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-first-sports-bra-got- stabilizing-start-180974427//.

Messner, Michael A. "Center of Attention: The Gender of Sports Media." In Taking the Field: Women, Men, and Sports, 91-134. University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Miller, Daniel. “Introduction.” In Clothing as Material Culture, edited by Susanne Küchler and Daniel Miller, 1-20. Clothing as Material Culture. Oxford, UK: Berg, 2005.