A Closer Look: Funerary Studies, Material Culture, and the Maya

Sarah Henzlik

Citation: Henzlik, Sarah. “A Closer Look: Funerary Studies, Material Culture, and the Maya.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, December 3, 2021.

Abstract: The following analysis investigates literature from the field regarding a carbonate stone bowl, designated as “Bowl with Anthropomorphic Cacao Trees,” found in a tomb and located today in the collection of Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C. The three-roundel bowl is regarded to feature a personified Chocolate God as its central figure. On the other hand, some scholars in the field, including Simon Martin and Karl Taube, posit that the figure considered the “Chocolate God” on this funerary bowl is instead intended to represent the Maize God embodying the Chocolate God in a call for generational rebirth. The following seeks to offer an object biography under the lens of funerary studies and the material culture of the Maya. Visual analysis and study of Maya religious principles are also employed.

Keywords: Art History, Museum Studies, Mesoamerica, Maya, Funerary Studies, Object Biography

The present-day sweet treat of chocolate, or cacao, was more than a dessert in ancient Mesoamerica: it was a delicacy reserved for the elite and gods.[1] Cacao’s significance was apparent to Spaniard Bernardino de Sahagún upon arrival to present-day Mexico.[2] In 1550, Sahagún noted, “then, in his house, the ruler was served his chocolate, with which he finished [his repast]- green, made of tender cacao, honeyed chocolate made with ground-up dried flowers - with green vanilla pods; bright red chocolate; orange-colored chocolate; rose-colored chocolate; black chocolate; white chocolate.”[3] Chocolate, embodied as the reverent Chocolate God, was omnipresent throughout daily life, iconography, and at the core of religiosity for the royal Maya court.[4] The Chocolate God is thought to be a relative of the Maize God, one of the central gods in Mesoamerica: the former as the nourishment of the elite and gods, the latter as the lifeblood of the people at large.[5] The following analysis investigates literature from the field regarding a carbonate stone bowl, designated as “Bowl with Anthropomorphic Cacao Trees,” found in a tomb and located today in the collection of Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C. The three-roundel bowl is regarded to feature a personified Chocolate God as its central figure. On the other hand, some scholars in the field, including Simon Martin and Karl Taube, posit that the figure considered the “Chocolate God” on this funerary bowl is instead intended to represent the Maize God embodying the Chocolate God in a call for generational rebirth. The following seeks to offer an object biography under the lens of funerary studies and the material culture of the Maya.

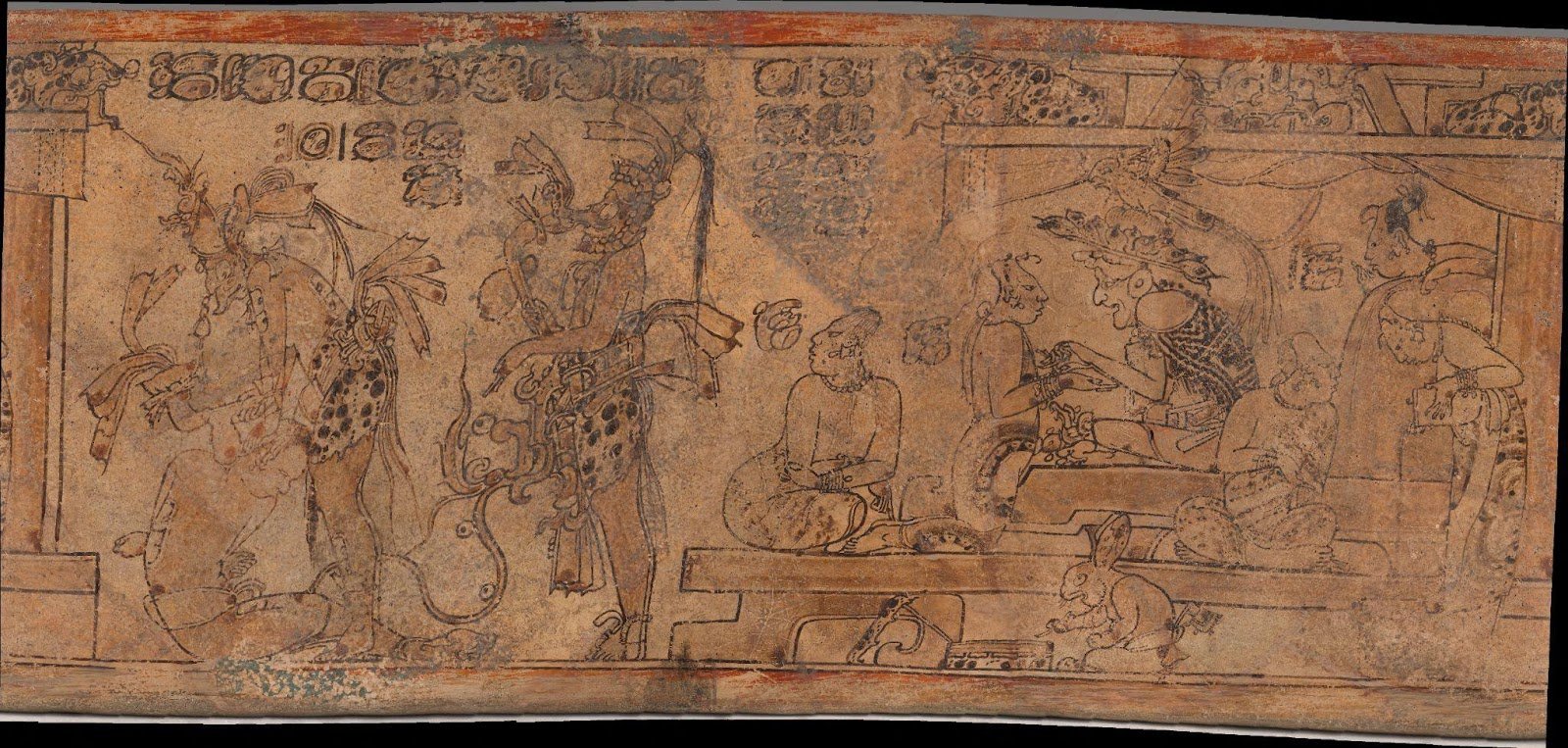

Figure 1: The Princeton Vase, AD 670-750 Late Classic. Ceramic with red, cream, and black slip, with remnants of painted stucco. h. 21.5 cm., diam. 16.6 cm. (8 7/16 x 6 9/16 in.), Princeton University Art Museum. Museum purchase, gift of the Hans A. Widenmann, Class of 1918, and Dorothy Widenmann Foundation.

As Meredith Dreiss recounts in her book, “Chocolate: Pathway to the Gods,” chocolate held great symbolic significance to the Maya. Preparing chocolate was labor-intensive: from the domestication, cultivation, and harvesting of the cacao tree into pure chocolate with chemistry-like precision, it is not surprising why the cacao seed and tree became sacred entities throughout Mesoamerica— the amount of effort needed to produce one cup took almost religious-like commitment.[6] As such, the frothy cacao drink acquired elite status during rituals and feasts, becoming the beverage of choice for gods and royals. In a rollout of the Princeton Vase (Figure 1), female members of the royal court prepare the delicacy of the froth of chocolate at the far right of the scene. While these women are presumably using tall ceramic vessels to circulate the aeration of the chocolate drink, “Bowl with Anthropomorphic Cacao Trees” (Figure 2) is made of carbonate stone. It can fit in the palms of two cupped hands, reminiscent of a drinking cup.[7] The bowl, dated to about 400-500 CE, has hieroglyphic captions and three oval roundels that feature scenes of a human-like figure.[8]

Figure 2: Maya, Bowl with Anthropomorphic Cacao Trees, 400-500 CE. Carbonate stone,h. 8.6 cm., diam. 15.9 cm. (3.4 x 6.3 in.) © Dumbarton Oaks, Pre-Columbian Collection, Washington, D.C.

Figure 3: Maya, Bowl with Anthropomorphic Cacao Trees, 400-500 CE. Carbonate stone, h. 8.6 cm., diam. 15.9 cm. (3.4 x 6.3 in.) © Dumbarton Oaks, Pre-Columbian Collection, Washington, D.C.

Two of the scenes survive today (Figure 2). In one scene (Figure 3), the figure appears seated on a mat-decorated seat with markings on his arms and legs that look like ripe cacao pods and wood motifs. The figure points to a vessel akin to a ceramic chocolate frothing device. The figure appears to wear a beaded belt and jade ornaments.[9]

As a result, many historians attribute this representation to an anthropomorphized Chocolate God.[10] However, some scholars, including Simon Martin, in his article, “Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion: First Fruit from the Maize Tree and other tales from the Underworld,” suggest that the characteristics of the figure’s head—with a sloping brow, prominent forehead decoration (possibly an ajaw headdress) and tonsured hairstyle, like long wisps of an ear of corn—align to the iconography of the Maize God (Figure 4, personage on the left).[11]

Figure 4: Maya vase rollout, Justin Kerr, [K1185], Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C.

Compounded by the figure pointing to a chocolate pot, the glyph directly above his hand joins the sign of “TE” (tree) with the head of the Maize God (Figure 2).[12]Also featured in the hieroglyphic caption is iximte (maize tree or maize god tree), preceded by a term describing the figure’s pose.[13] The next glyph names the figure who impersonates this entity as a supernatural cacao tree, offering a possibility that the figure is the revered Maize God embodying the Chocolate God.[14]

The Maize God, also known as Hun-Hunahpu, is a significant figure in Mesoamerican iconography. Much has been published about the Maize’s God appearance, and it has generally been agreed upon in the field that his physical description remains consistent across a variety of extant media.

Nicolas Hellmuth, as cited in Karl Taube’s reckoning of the Maize God, notes that the Maize God typically appears as:

A youthful male having an especially elongated and flattened head. The hair is usually separated into a brow fringe and capping tuft by a tonsured horizontal zone, giving the head a ‘double-domed’ appearance. The entity wears a series of distinctive costume elements, among them: a frequent tassel projecting from the back of the head, a long-snouted brow piece resembling the Palencano Jester God, and above, at the top of the head, another longnosed face commonly supplied with beaded elements...The most striking physical attribute of the youthful entity is the extremely elongated head. The “double-domed,” or tonsured coiffure is especially suggestive of the maize cob, as the lower hair resembles the pulled back husk, and the capping tuft, the maize silk.[15]

Although several episodes in the Maize God’s complex journey remain to be fully uncovered, it is agreed upon in the field that the tradition of Hun-Hunahpu is one of sacrifice and resurrection, reflecting the seasonal cycle of harvesting crops.[16] Much can be gained from studying the Maize God’s ‘birth’: a young lord who is transformed into organic material.[17] Its symbolism of continual death and rebirth, duality, and abundance make it ripe for iconography on funerary objects. For instance, in one variation of the Maize God’s ‘emergence theme,’ Karl Taube recounts that the “tonsured youth rises out of a cracked tortoise carapace. The Headband Twin with jaguar skin markings holds a downturned jug over the emergent youth, appearing to water the rising figure.”[18] In another variation, likely meaningful for members of the warrior class who sacrifice their lives for their people, three deity boatmen hold a flint to the neck of the Maize God, suggesting that as a result of the Maize God’s decapitation, the people received the three successive stages in the maize agricultural cycle.[19]In fact, on one vessel, today in the collection of the Museo Popol Vuh in Guatemala, the Maize God’s head appears in the trunk of a cacao tree among ripe cacao pods (pg. 165 of the hyperlinked article), promoting the strength of the divine relational ties between the Maize God and the Chocolate God.[20]

The Maize God’s ‘death’ represents the Maya belief that upon death, the soul leaves the body, and subsequent generations grow from the body’s organic material.[21] Due to the Maize God’s prominence, many Maya rulers chose to have their likeness depicted as the Maize God in funerary objects. One such ruler was Pakal, from the Maya city state of Palenque (located in what is today considered southern Mexico). Imagery on Pakal’s sarcophagus seeks to cement the connection between Pakal’s death (as the Maize God) and continuity of the ancestral line of the ruling class of Palenque. This is accomplished by depicting ten fruit trees growing from the cracks in the ground of the Maize God’s (Pakal’s) sarcophagus, including crops such as avocado, guayaba, nance, zapote, and cacao, creating an “Orchard of the Ancestral Dead,” (pg. 162 in hyperlinked article).[22] Pakal’s mother, Lady Resplendent Quetzal, represented Pakal’s most prominent relational tie to the ruling class. Thus, to demonstrate Lady Resplendent Quetzal’s prominence, she is depicted as being associated with cacao, highlighting cacao’s place as a refreshment of the gods and rulers (pg. 162 in hyperlinked article).[23]

This imagery demonstrates that from the Maize God’s death came life and nourishment for humanity. This concept can be expanded to possibly include thoughts of vegetation, growth, abundance, generational rebirth, and transformation. These themes permeate this bowl and act as a conduit to redemption and comfort for the deceased person’s spirit. By connecting Pakal and this unidentified patron of “Bowl with Anthropomorphic Cacao Trees” funerary iconography, the patron makes a bold call to demonstrate direct lineage from the gods to the elite class: cacao and maize, nourishment for eternity.

This visual analysis seeks to offer more than solely an alternative classification of one bowl’s iconography. Compounded by the compelling images that suggest a representation of the Maize God, the circumstances under which the bowl was found also point to a deeper call. As the fundamental metaphor for life and death for the Maya, the story of the Maize God acted as the core for much of their ritual and daily life.[24] James Mondloch notes that the “human desire for immortality is satisfied in Maya religion less by removal to a heavenly paradise than by reincarnation in future generations, specifically as grandchildren… believing humanity to be composed of corn dough and the life cycle of the Maize God serv[ing] to ‘re-process’ the material from which all people are made.”[25] By placing a bowl with the image of the Maize God, a revered deity of the people, embodying the delicacy of the elites and gods—the Chocolate God in the form of a tree—the object plays two roles: a drinking vessel that holds the chocolate drink to nourish the deceased person’s spirit once it separates from the body, and a religious embodiment of organic material ripe for rebirth to demonstrate the piety of the patron.

This object biography intends to offer an example of the intersections of religiosity, daily life, and ritual among the Maya. As James Fitzsimmons and Izumi Shimada note in “Living with the Dead: Mortuary Ritual in Mesoamerica,” object biographies of funerary objects share insightful perspective “not only the dead themselves but also the mind-set of the living.”[26] Regardless of the figure’s intended identity on “Bowl with Anthropomorphic Cacao Trees,” it is clear that the patron sought comfort in aligning himself with a divine presence. More than likely, the patron decided on the bowl’s design well in advance of his death, affording him time to consider the legacy he would like to leave for his descendants to carry forward. As Dr. Patricia McAnany notes, many researchers today are “accustomed to a western, medicalized approach to death as something that can be recorded down to the minute—an acute moment when the breath of life ceases.”[27]As researchers from a variety of traditions and backgrounds study the Maya, it is truly thought-provoking to consider the association of organic material with life and death and the implications this pervasive organizing principle can have on one’s experience day in and day out.

Endnotes

[1] Mary Miller and Karl Taube, The Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya (London: Thames and Hudson, 2018), “cacao.”

[2] .Meredith Dreiss, Chocolate: Pathway to the Gods (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2008), 105.

[3] Dreiss 2008, 105.

[4] Miller and Taub 2018, ‘cacao’

[5]Karl Taube, “The Classic Maya Maize God: A Reappraisal.” In Fifth Palenque Round Table 1983, edited by Merle Greene Robertson,(San Francisco: The Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute), 175.

[6] Dreiss 2008, 105.

[7] Pre-Columbian Collection, “Bowl with Anthropomorphic Cacao Trees.” Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Trustees for Harvard University, Accessed on February 9, 2020. http://museum.doaks.org/OBJ?sid=65877&rec=2&port=2652&art=0&page=2

[8] Pre-Columbian Collection, “Bowl with Anthropomorphic Trees”.

[9] Nicholas Hellmuth as cited in Karl Taube, “The Classic Maya Maize God: A Reappraisal,” 181.

[10] Pre-Columbian Collection, “Bowl.” Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

[11] Simon Martin, “Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion: First Fruit from the Maize Tree and other tales from the Underworld,” in Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History Of Cacao, ed. Cameron L. McNeil (Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 2006), 156.

[12] Martin 2006, 156.

[13] Martin 2006, 156.

[14] Martin 2006, 156.

[15] Nicolas Hellmuth as cited in Karl Taube, “The Classic Maya Maize God: A Reappraisal,”172.

[16] Nicolas Hellmuth as cited in Karl Taube, “The Classic Maya Maize God: A Reappraisal,”172.

[17] Taube 1983, 174.

[18] Taube 1983, 174.

[19] Taube 1983, 175.

[20] Martin 2006,164.

[21] Martin 2006,159.

[22] Martin 2006, 161.

[23] Martin 2006, 161.

[24] Martin 2006, 163.

[25] James Mondloch as cited in Simon Martin, “Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion: First Fruit from the Maize Tree and other tales from the Underworld,” in Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History Of Cacao, ed. Cameron L. McNeil (Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 2006), 163.

[26] James L. Fitzsimmons and Izumi Shimada, eds. Living With The Dead: Mortuary Ritual In Mesoamerica. University Of Arizona Press, 2011.

[27] Patricia A.McAnany, “Toward a Hermeneutics of Death: Commentary on Seven Essays Written for Living with the Dead.” In Living with the Dead: Mortuary Ritual in Mesoamerica, edited by James L. Fitzsimmons and Izumi Shimada, 231–40. University of Arizona Press, 2011.

Bibliography

Coe, Michael D., Javier Urcid, and Rex Koonz. Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. (Eighth Edition). London: Thames and Hudson, 2019.

Dreiss, Meredith L., and Sharon Edgar Greenhill. Chocolate: Pathway to the Gods. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2008.

Fitzsimmons, James L., and Izumi Shimada, eds. Living With The Dead: Mortuary Ritual In Mesoamerica. University of Arizona Press, 2011.

Martin, Simon. “Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion: First Fruit from the Maize Tree and other tales from the Underworld.” In Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History Of Cacao, edited by Cameron L. McNeil, 154-183. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 2006.

McAnany, Patricia A. “Toward a Hermeneutics of Death: Commentary on Seven Essays Written for Living with the Dead.” In Living with the Dead: Mortuary Ritual in Mesoamerica, edited by James L. Fitzsimmons and Izumi Shimada, 231–40. University of Arizona Press, 2011.

Miller, Mary, and Karl Taube. The Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames and Hudson, 2018.

Pre-Columbian Collection. “Bowl with Anthropomorphic Cacao Trees.” Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. Trustees for Harvard University. Accessed on February 9, 2020. http://museum.doaks.org/OBJ?sid=65877&rec=2&port=2652&art=0&page=2

Taube, Karl. “The Classic Maya Maize God: A Reappraisal.” In Fifth Palenque Round Table 1983, edited by Merle Greene Robertson, 171-181. San Francisco: The Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute.