The Female Body as Commodity:

The Woman in Alphonse Mucha’s JOB Poster (1896)

Margaryta Golovchenko

Citation: Golovchenko, Margaryta. “The Female Body as Commodity: The Woman in Alphonse Mucha’s JOB Poster (1896).” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, October 9, 2020.

Abstract: The work of iconic Art Nouveau artist Alphonse Mucha has long been a source of fascination for its appealing aesthetic qualities, yet there has been little in the way of critical analysis of his work. Considering that Mucha is most famous for the commercial posters he produced around the turn of the century, all of which featured a woman as their subject, this results in a gap in the academic literature that overlooks the fact that it is arguably the women who are the real “product” being advertised. This paper focuses on one of Mucha’s iconic posters, the 1896 poster for JOB cigarette papers, the first of two Mucha produced. It argues that femininity is performed in Mucha’s poster the way that Judith Butler describes in her article “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution,” as the female subject wears modernity like a skin and performs freedom without truly being a liberated woman.

After contextualizing Mucha’s JOB poster in the social and economic climate of fin de siècle Paris, this paper will speak to the complex role women played in nineteenth-century society, as companies were slowly beginning to advertise more specifically towards women, despite the persistent restrictions of patriarchal society.

Key words: Mucha, Advertising, Paris, Poster, Women, Femininity, Nineteenth-Century, Fin de Siècle

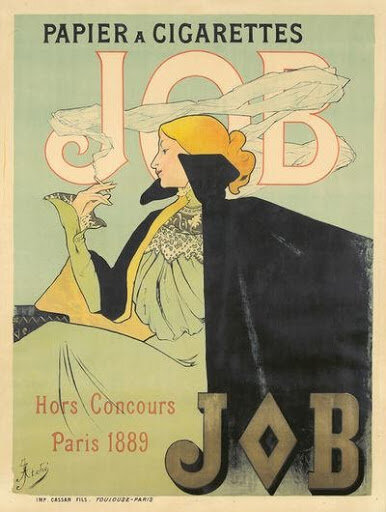

The soft pastel colour scheme and delicate, swirling lines of Alphonse Mucha’s iconic posters were the source of the artist’s overnight success, with stories of the lengths to which people went to acquire them only adding to their popularity. In the posters that Mucha produced during the last decade of the nineteenth century at the peak of his career, women are nestled within these feminine decorative forms in such a way that they initially blend into their surroundings. Women are the primary advertising tactic in Mucha’s posters, trying to sell products that range from alcohol and biscuits to bicycles and even train travel. It is therefore difficult not to believe that, by placing women in the same pictorial space with items that women were discouraged from using or consuming, Mucha is making a comment on encouraging greater freedom for Parisian women. The first of two JOB posters that Mucha designed for the Joseph Bardou Company—JOB for short—in 1896 (Figure 1) is an excellent example of the tension between the aesthetic and the moral side of the work, which, in this case, results in a paradoxical representation of the female subject. At a time when feminist ideas were in the air and women were slowly gaining freedom of mobility and in consumerism, the woman in Mucha’s JOB poster seems to support the rise of the emancipated woman by showing her smoking and basking in an unrestrained expression of female sexuality and pleasure. However, Mucha’s strong interest in decorative elements and design was closely interlinked with his interest in the female form to the point where “a woman, for him, was not a body, but beauty incorporated in matter and acting through matter,” [1] in the words of his son, Jiri Mucha. With this in mind, as well as the fact that the very existence of the commercial poster is rooted in its in mass-producibility, the 1896 JOB poster proves to be quite the opposite. Rather, the poster exemplifies the dehumanization and commodification of women that occurred in fin-de-siècle Paris, as the female subject wears modernity like a skin without truly embodying the ideals of the liberated woman.

Before looking at the function and aesthetic qualities of Mucha’s poster, it is imperative to consider its existence within the larger framework of nineteenth-century shopping culture and poster production. The Arcades Project, the seminal work of Walter Benjamin, reveals how influential the arcades were in transforming Parisian shopping culture. Benjamin describes the arcades as “rue-galerie,” or “street-galleries,” that are built in a “continuous peristyle” and “heated in winter and ventilated in summer.”[2] Shoppers—predominantly male, as shall be discussed later—were therefore invited to linger in the space, to “set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite,” [3] in the words of Charles Baudelaire. Significantly, the arcades were also a site of tension between the modern and the traditional, technology and art. On the one hand, they were the direct product of technological development, made possible by “the beginning of iron construction,” as well as “the scene of the first gas lighting.”[4] On the other hand, the arcades were a space where one could encounter culture and be enlightened by it, since “[t]he government had wanted the streets belonging to the people of Paris to surpass in magnificence the drawing rooms of the most powerful sovereigns.”[5] Yet the reality of modern society could not be kept out of this commercial utopia, and prostitutes proved to be especially problematic. A threat to the patriarchal and capitalist vision of society, they drew attention towards themselves and away from the goods, “and the people who enjoyed this spectacle were never the ones who patronized the local businesses.”[6]

Mucha’s JOB poster embodies this tension between art and commerce, forced to navigate between these two spaces because of its function. One of the most discrete yet striking ways in which this is represented is in the hair of the female subject. In Art Nouveau, hair was exaggerated “almost to the point of obsession, thereby extending the erotic qualities already associated with Woman,” in order to visually reinforce the belief that women were “fragile, helpless object[s], used in a decorative and literal sense to adorn the household.”[7] While the hair in the poster certainly echoes the swirl of cigarette smoke in the background, the intricate yet rigid-looking locks also look like they are made of metal, losing any kind of natural softness. The woman’s luscious curls thus serve as a visual reminder that the Art Nouveau movement was not always associated with plantlike forms.[8] In fact, as Debora Silverman points out, the term “art nouveau” originally came into being in 1889, when it was applied to new iron monuments such as Gustave Eiffel’s, and was “associated with the values of youth, virility, production, and democracy.”[9] The woman in Mucha’s JOB poster is the visual and artistic equivalent of the wrought iron details that were added as embellishments to buildings like the Hôtel Tassel by Victor Horta (Figure 2), their task to please the eye without disturbing the structural integrity of the building. Moreover, the medium of the poster itself embodies technological progress, since “the poster could not exist before the specific historic conditions of modern capitalism” and had to “await the invention of [the] far cheaper and more sophisticated color printing process — lithography[.]”[10] The woman in Mucha’s poster is therefore doubly ‘modern’ in the technological sense, referring to advancements like iron construction and owing her existence to technological efficiency.

Women’s place within this new commercial and technological culture was equally ambivalent. Despite progressive gestures, like the inclusion of the female noun “flaneuse” in the 1866-79 edition of the Larousse Grande dictionnaire, the reality was that women were still not allowed to “exceeded the definition of the respectable ‘flaneuse.’”[11] As Ruth Iskin notes, “advertising posters did not promote modern women’s broader agendas.”[12] The encouragement directed towards women to consume was undermined by the fact that the products they were truly urged to purchase—like perfume and biscuits—were codified as female and “sanctioned” for purchase by society, meant to be consumed in the domestic space over which women were given as “a powerful antidote to the femme nouvelle.”[13] The situation was even more pessimistic in the fine arts, as portrayals of women were generally polarized: women were characterized either as femme fatales or as ephemeral, fantasy creatures. Femme fatales, more generally known as the filles d’Eve, were “associated with ideas of decadence and degeneration” and were considered dangerous because “their curiosity caused man’s downfall.”[14] If they were not viewed as a threat, women were portrayed as one of several Romanticized “types,” namely the fairy, the muse, and the visionary saint—with the androgyne as the ideal.[15] In these cases, women were stripped not only of their individuality, but also of any mentions of female sexuality and modernity. Nevertheless, there was significant feminist push-back against patriarchal society, taking the form of regular feminist congresses, where issues like education and pay equality were raised.[16] There was also a rise in organizations known as the club des femmes, which emerged in the 1870s after women were given the right to gather in larger groups.[17] However, this kind of female-led call for equality and freedom led to further marginalization, with feminists “treated as outcasts of society who might prove dangerous if given the right to vote” and then discredited by male illustrators as being either “old, ugly, and dangerous, or […] beautiful but extremely frivolous.”[18]

If the JOB poster is considered in the context of this dichotomy, then the (subjective) beauty of the woman in the poster falls into a third category: a strategy targeting the male viewer. Since men were the primary consumers of addictive substances, women were used in advertisements to encourage consumption by “underscor[ing] the traditional connection of women to nature […to] promote these dangerous products as perfectly natural and safe.”[19] It is worth noting that this strategy of using beauty to appeal to the male viewer resulted in a direct contradiction to another tactic used at the time, which was to dissuade women from smoking by emphasizing premature aging.[20] Produced by a man, the JOB poster is not an explicit feminist call for women to begin smoking in defiance. Rather, Mucha’s poster is an example of how beauty was wielded as a weapon by society to suit its own needs, portraying women either as beautiful and passive facilitators of economic consumption, or as unattractive when they tried to assume a more active role.[21]

By contrast, a poster like Jane Atché’s contribution to the genre of cigarette posters (Figure 3) is much more dangerous, in part because of the sophisticated and restrained appearance of the female subject. Atché’s model is a “highly fashionable upper-middle-class woman” who has “retain[ed] her social distinction […with no] implication of a deliberate act of defiance of gender restrictions on her part.”[22] The fact that Atché is a woman depicting such a behaviour is arguably more threatening, as this speaks to the kind of ideological, and later physical, rallying among women that was feared for so long by male-dominated society. Atché’s poster makes it all the more difficult to reconcile the contradicting desires of appealing to men but dissuading women from smoking, just as “[f]or bourgeois women, the propriety of staying close to home and venturing out only when chaperoned conflicted with the economic imperative to seek and purchase.”[23] The time period during which Mucha was producing posters, such as the one for JOB, was fraught with the kind of dualities discussed thus far. These ranged from debates about the medium (posters) and the subject matter (woman), to the more extreme tendency of gendering mass culture—things like posters and popular fiction—as inferior and female, while privileging high culture—like fine art—by viewing it as male.[24] In other words, the contemporary advertising had the complex task of navigating between women’s desire for physical and economic freedom and the fear of patriarchal society of this occurring—all the while keeping in mind both the spoken and unspoken rules about how women can be portrayed and how they can engage as potential consumers.

The iconography of Mucha’s JOB poster becomes even more significant, the deceptively unrestrained and ‘masculine’ behaviour of the female subject further exemplifying the kinds of contradictory binaries discussed earlier. Although the poster is intended to advertise cigarette papers and smoking, the woman dominates the composition of the poster. The female figure, as the subject of and the enactor of the smoking, overshadows the product—literally in visual space and metaphorically. There is little doubt that Mucha’s poster depicts its female subject in a state of self-absorbed pleasure. Her closed eyes and body leaning out of the depicted decorative border towards the viewer allude to a conscious withdrawal from reality and suggest an awareness of a beholder’s gaze. At this time, there was much anxiety about women withdrawing from the company of men as it was feared that a secluded woman would indulge in sexual pleasure.[25] The fact that Mucha’s poster is advertising cigarette paper rather than cigarettes plays on this fear of women being left alone. By depicting the woman smoking in a kind of visual ‘nowhere,’ rather than in a café or some other recognizable public space, Mucha implies that the act of rolling the cigarette has already taken place beyond the controlling gaze of the viewer.[26] When combined with the libidinal connotations of smoking that emerged around this time, the poster becomes a promise of something more for the male viewer.[27] Drawing on the scopophilic desire for the woman as an object, where “looking itself is a source of pleasure,”[28] the poster reinforces the fact that any potential female viewer–consumer will always be passive. The increased buying power that women gained at this time only furthered the illusion of an active male because they were never allowed the luxury of anonymity that the flaneur does.[29] As well as being literally displayed along with the products they were advertising, a woman who would be stopping to look at the poster would have also been putting herself on display due to how restricted her movement would have been at this time.[30]

The anonymity that was denied to women at this time is imposed upon the female subject in Mucha’s poster. However, it is difficult to read this as a victory, for this very anonymity is linked to the dehumanization inherent in the process of mass production. It is not only a matter of the inability to identify the woman in the JOB poster by name (the way that Mucha’s posters for the theatrical productions of Sarah Bernhardt would have been recognizable to his contemporary viewers). The additional issue of anonymity at stake to which I am referring stems from the generic type of beauty seen in the woman in the JOB poster. It is a beauty found in many of the posters during this time period that transformed the female subject into a vessel that fed the desire for fantasy and escapism.[31] Similarly, Mucha had a tendency of equating women with objects such as jewellery. Not only did he depict the two in the same visual space, but he also placed more emphasis on the object than on the woman.[32] Even the photographs Mucha took of real women to use as references were often “improv[ed] […] to express his philosophical ideas about beauty and goodness,” suggesting that women, just like the products they advertised, are expendable.[33] For Mucha, the social construct of gender took priority over the individual experience of the binary sexes, where it is but one part of an individual’s identity: as Judith Butler observes, “to be a woman is to have become a woman.”[34] The woman in the JOB poster performs her femininity and sexuality no different from Butler’s argument that gender identity is “instituted through a stylized repetition of acts.”[35] She does not cross the boundary of gender norms by taking her behaviour outside of the theatrical space of the capitalist poster, where “one can say, ‘this is just an act,’ and de-realize the act[.]”[36]

The 1896 poster is in sharp contrast to the second poster that Mucha produced for JOB in 1898 (Figure 4), for although the model in the second poster continues this thread of anonymity, there are key differences in the body language and general atmosphere between the two. The 1898 poster shifts the emphasis from the model’s hair to her flowing dress—another popular subject in Art Nouveau.[37] Similarly, details such as the change in hair colour from light to dark and the replacement of the comb for roses in her hair add to the shift in focus from the female subject to the product in the 1898 poster. Such an emphasis is further suggested by the increased visibility of the lettering at the top of the composition and the card with the company name that the female figure holds. The relationship between the woman and the cigarette also differs between the two posters. Looking at the 1898 poster, there is the sense that Mucha has depicted a still from a film and that, if the poster were ‘unpaused’ and the film allowed to continue, the woman’s intent gaze at the cigarette would give way to a wrinkling of her nose in displeasure. This woman is not the highly sexualized and self-absorbed figure found in the 1896 poster. While the figure of the earlier poster is the epitome of Baudelaire’s argument in support of makeup, arguing that Woman “has to astonish and charm us [—] as an idol, she is obliged to adorn herself in order to be adorned [—],”[38] the woman in the later poster is modest and youthful in her behaviour, with the cigarette as a stand-in for the sexuality she appears to be in the process of discovering.

There are two differences that are worth noting, the first of which is the significance of the decorative border. In the 1896 poster, it is thicker and more ornate like a picture frame, thereby going against the call of contemporary critics to remove the frame and democratize the artwork.[39] The frame is also what creates the so-called “Byzantine effect” that Mucha was known for, speaking to his composite style that was “somewhat Byzantine and combining classical memories with a very contemporary laguor,”[40] and effectively giving an exotic twist to modernity without resorting to an extreme form of Orientalization. Even more interesting is the way the woman’s knee protrudes outside of the frame. In doing so, it disrupts the visual integrity of the pictorial space, much like the image of a woman smoking disrupts the patriarchal status quo. This detail leads back to the question of this essay’s concern: how modern—in a liberal sense—is the female subject of Mucha’s 1896 poster? The fact that the woman found a way to break out of her imposed confinement suggests she truly might be independent enough to move as she pleases. The second and subtler, yet arguably more important, difference lies in the placement of the model in the 1898 poster compared to the one from 1896. Whereas the woman in the later poster is placed within the central circle as if a flower or a jewel on the dish, the woman in the 1896 poster is framed in a halo-like fashion by the letter “O” in JOB. Whether unintentional or deliberate, this slight detail further disrupts the polarization between male and female, active and passive, artistic and commercial, that society worked so hard to set up and reinforce. While it may not fully redeem the woman in the eyes of the patriarchy, it at least softens the potential criticism towards her.

When examining the formal elements of a poster as a work of art, it is important to keep in mind its function as an advertisement, for as Susan Sontag rightly points out: “Unlike a painting, a poster was never meant to exist as a unique object.”[41] To concentrate solely on the poster’s artistic value would be equivalent to applying Walter Benjamin’s argument against technological reproduction while ignoring the context in which the artwork functioned.[42] That is not to say, however, that Benjamin’s notion of the aura is completely irrelevant in this case either. With regards to Mucha’s poster, it is not the integrity of the poster as an object that is being diminished, but the aura of the individual. Benjamin’s original definition of the aura—a “strange tissue of space and time: a unique apparition of a distance, however near it may be”—nonetheless holds true, since Mucha’s poster is a product of its time and draws on ideas about gender, art, and consumption that would likely not be picked up by a viewer today. [43]

How successful, then, is Mucha’s poster, and what does “success” mean? Is it the poster’s ability to “grab the attention of distracted, rushing passersby, the poster had to be designed to communicate in a split second”?[44] If so, then Mucha’s poster is unsuccessful, for as the French critic G. de Saint-Aubin points out, the poster fails at its function because of visual crowdedness despite its “artistic superiority.”[45] Is it the poster’s ability to pass as a work of art? In this case, it is highly successful, for the same reason outlined above. Sontag’s assertion that “what is recognized as an effective poster is one that transcends its utility in delivering [its] message],” is similarly in question when applied to Mucha’s poster.[46] As mentioned earlier, the intention of the poster is uncertain, whether it is encouraging men (but not women) to smoke, for women to see themselves in the subject, or simply perhaps Mucha’s promotion of the JOB brand.

I propose that Mucha’s poster can be interpreted as a clone that “represents the destruction of the natural order” through the amplification and distortion of parts of modernity.[47] The poster should not be treated as “a picture or specimen, [where] we ask, Is this a good example of X […but as] an image, [where] we ask, Does X go anywhere[.]”[48] The female subject is dehumanized, her existence inseparable from the medium of the poster and its reproducible nature. Mucha’s 1896 JOB poster has been presented as a case study both for the body of similar works that the artist produced between 1890 and 1905, as well as for how the freedom that women were slowly obtaining nonetheless came with limitations. It is therefore difficult to firmly assert whether Mucha deliberately intended the hints of independence discussed in this paper to have been understood as such. Yet, even though the poster continues to cater primarily to the male viewer, it is difficult not to see this work in a hopeful light, to interpret the protruding knee of the female subject as a foreshadowing of better times to come.

Endnotes

[1] Jan Thompson, “The Role of Woman in the Iconography of Art Nouveau,” in Art Journal 31, no. 2 (1971-72): 162.

[2] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1999), 42.

[3] Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life,” in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, translated and edited by Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon Press, 1964), 9.

[4] Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 3.

[5] Benjamin, 55.

[6] Benjamin, 43.

[7] Thompson, “The Role of Woman in the Iconography of Art Nouveau,” 162, 159.

[8] Debera L. Silverman, Art Nouveau in Fin-de-siècle France: Politics, Psychology, and Style (Berkley: University of California Press), 2.

[9] Silverman, 1-2, 4.

[10] Susan Sontag, “Posters: Advertisement, Art, Political Artifact, Commodity,” in Looking Closer 3, ed. Michael Bierut, (New York: Allworth Press, 1999), 197.

[11] Ruth E. Iskin, “The Pan-European Flaneuse in Fin-de-Siecle Posters: Advertising Modern Women in the City,” in Nineteenth-Century Contexts 25, no. 4 (2003): 334, 351.

[12] Ruth E. Iskin, “Popularising New Women in Belle Epoque Advertising Posters,” in A ‘Belle Epoque’?: Women in French Society and Culture, 1890-1914, ed. Diana Holmes and Carrie Tarr, (New York: Berghahn Books, 2006), 111.

[13] Silverman, Art Nouveau in Fin-de- siècle France, 74.

[14] Mary Slavkin, “Fairies, Passive Female Sexuality, and Idealized Female Archetypes at the Salons of the Rose + Croix,” in RACAR 44, no. 1 (2019): 65; Elizabeth K. Menon, Evil by Design: The Creation and Marketing of the Femme Fatale (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006), 20.

[15] See Slavkin, “Fairies, Passive Female Sexuality, and Idealized Female Archetypes at the Salons of the Rose + Croix,” 65-67.

[16] Diana Holmes and Carrie Tarr, “New Republic, New Women?,” in A ‘Belle Epoque’?: Women in French Society and Culture, 1890-1914, ed. Diana Holmes and Carrie Tarr, (New York: Berghahn Books, 2006), 12-13.

[17] Menon, Evil by Design, 64.

[18] Menon, 64

[19] Menon, 69.

[20] Menon, 74.

[21] Iskin, “Popularising New Women in Belle Epoque Advertising Posters,” 99.

[22] Ruth E. Iskin, The Poster: Art, Advertising, Design, and Collecting, 1860s-1900s (Hanover: Dartmouth College Press, 2014), 277-78.

[23] Holmes and Tarr, “New Republic, New Women?,” 17.

[24] See Andreas Huyssen, “Mass Culture as Woman: Modernism’s Other,” in After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), 49-50.

[25] Dolores Mitchell, “The ‘New Woman’ as Prometheus: Women Artists Depict Women Smoking,” in Women’s Art Journal 12, no. 1 (1991): 4.

[26] Menon, Evil by Design, 81.

[27] Dolores Mitchell, “The Iconology of Smoking”, in Source: Notes in the History of Art 6, no. 3 (1987): 28.

[28] Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Film Theory and Criticism, edited by Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 835.

[29] Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life,” 9.

[30] The act of chaperoning described by Holmes and Tarr is arguably another form of parading that reinforced the commodification and display of the female body through advertisements. See Holmes and Tarr, “New Republic, New Women?,” 17.

[31] Gabriel Mourey, Foreward, in The Art Nouveau Style Book of Alphonse Mucha: All 72 Plates from ‘Documents decoratifs’ in Original Color, ed. David M.H. Kern (New York: Dover Publications, 1980), n.p.

[32] It is telling that Mourey writes that Mucha “never tortures flowers when he stylizes them; he likes them too well to harm them; his love for them is too passionate to inflict the slightest injury to them” (see note [33] above).

[33] Kristine Sommervile, “The Photographic Sketchbook of Alphonse Mucha,” in The Missouri Review 39, no. 4 (2016): 76.

[34] Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay on Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” in The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology, ed. Donald Preziosi, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 358.

[35] Butler, 356.

[36] Butler, 363.

[37] Thompson, “The Role of Woman in the Iconography of Art Nouveau,” 158.

[38] Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life,” 33.

[39] Iskin, The Poster, 42

[40] Mourey, n.p.

[41] Sontag, “Posters,” 199.

[42] See Iskin, The Poster, 26-29.

[43] Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility (Second Version),” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, edited by Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2002), 104-5.

[44] Iskin, The Poster, 179.

[45] Iskin, The Poster, 183.

[46] Sontag, “Posters,” 200.

[47] W.J.T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 16.

[48] Mitchell, 87.

Appendix

Figure 1

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ‘JOB’ Cigarette Paper. 1896.

Colour lithograph, 66.7 x 46.4cm. Mucha Foundation, Prague. http://www.muchafoundation.org/gallery/themes/theme/advertising-posters/object/44 (accessed December 1, 2019).

Figure 3:

Jane Atché, Hors Concours (Job, Unrivaled). 1889.

Colour lithograph, 150 x 120cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France. https://www.artsy.net/artwork/jane-atche-job-2 (accessed December 1, 2019).

Figure 2:

Staircase at the Hôtel Tassel. 1892-93.

Architect Victor Horta designed for Emile Tassel. Brussels, Belgium.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H%C3%B4tel_Tassel#/media/File:Tassel_House_stairway.JPG (accessed December 1, 2019).

Figure 4:

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for “JOB” Cigarette Paper. 1898.

Colour lithograph, 149.2 x 101cm. Mucha Foundation, Prague.

http://www.muchafoundation.org/gallery/themes/theme/advertising-posters/object/45 (accessed December 1, 2019).

Works Cited

Baudelaire, Charles. “The Painter of Modern Life.” In The Painter of Modern Life and Other

Essays. Translated and edited by Jonathan Mayne, 1-40. London: Phaidon Press, 1964.

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin.

Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1999.

———. “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility (Second

Version.” In Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings. Edited by Michael W. Jennings, 101-

133. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2002.

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay on Phenomenology and

Feminist Theory.” In The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology, second edition. Edited

by Donald Preziosi, 356-366. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Holmes, Diana and Carrie Tarr. “New Republic, New Women?” In A ‘Belle Epoque’?: Women

in French Society and Culture, 1890-1914. Edited by Diana Holmes and Carrie Tarr, 11-22. New York: Berghahn Books, 2006.

Huyssen, Andreas. “Mass Culture as Woman: Modernism’s Other.” In After the Great Divide:

Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism, 44-62. Bloomington: Indiana University Press,

1986.

Iskin, Ruth E. “Popularising New Women in Belle Epoque Advertising Posters.” In A ‘Belle

Epoque’?: Women in French Society and Culture, 1890-1914. Edited by Diana Holmes and Carrie Tarr, 95-112. New York: Berghahn Books, 2006.

———. “The Pan-European Flâneuse in Fin-de-Siècle Posters: Advertising Modern Women in the City.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts 25, no. 4 (2003): 333-356.

———. The Poster: Art, Advertising, Design, and Collecting, 1860s-1900s. Hanover: Dartmouth College Press, 2014.

Menon, Elizabeth K. Evil by Design: The Creation and Marketing of the Femme Fatale. Urbana:

University of Illinois Press, 2006.

Mitchell, Dolores. “The Iconology of Smoking in Turn-of-the-Century Art.” Source: Notes in the

History of Art 6, no. 3 (1987): 27-33.

———. “The ‘New Woman’ as Prometheus: Women Artists Depict Women Smoking.” Woman’s Art Journal 12, no. 1 (1991): 3-9.

Mitchell, W.J.T. What Do Pictures Want? Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Mourey, Gabriel. Foreword. The Art Nouveau Style Book of Alphonse Mucha: All 72 Plates from

‘Documents decoratifs’ in Original Color. Edited by David M. H. Kern, n.p. New York: Dover Publications, 1980.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” In Film Theory and Criticism. Edited by

Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen, 833-44. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Silverman, Debera Leah. Art Nouveau in Fin-de-siècle France: Politics, Psychology, and Style.

Berkley: University of California Press, 1989.

Slavkin, Mary. “Fairies, Passive Female Sexuality, and Idealized Female Archetypes at the Salons

of the Rose + Croix.” RACAR 44, no. 1 (2019): 64-74.

Sommerville, Kristine. “The Photographic Sketchbook of Alphonse Mucha.” The Missouri Review

39, no. 4 (2016): 75-83.

Sontag, Susan. “Posters: Advertisement, Art, Political Artifact, Commodity.” In Looking Closer

3. Edited by Michael Bierut, 196-218. New York: Allworth Press, 1999.

Thompson, Jan. “The Role of Woman in the Iconography of Art Nouveau.” Art Journal 31, no. 2

(1971-72): 158-67.