To Walk Like an Egyptian:

Today’s Museum Visitors’ Experience in Connecting with The Individuals of Ancient Egypt

Jessica Romano

Citation: Romano, Jessica. “To Walk Like an Egyptian: Today’s Museum Visitors’ Experience in Connecting with The Individuals of Ancient Egypt.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, October 2, 2020.

Abstract: The experience of coming to know the individuals of the past through their material culture displayed within museums offers an understanding distinctive from those of the individuals who used and created them. In discussing how closely the modern museum visitors experience with artefacts on display reflects one’s relationship with material in the past, the different analytical theories, museum contexts and visitors are considered. The complexities of these interpretations and presentations of the past are showcased in the material of ancient Egypt as its various exhibitions and popularity have influenced just how accurately one can come to understand past individual experiences.

Key words: Museum studies, Egyptology, Hawara, Petrie Museum

Material objects are crucial to understanding not only what defines past cultures, but also the individual experiences of those who make up cultural groups. As such, they operate as vehicles to explore the object/subject relationship through physical and visual realities and representation.[1] In coming to an understanding of the experiences of the various individuals of the ancient past, a diverse audience must be considered in terms of interpretations within the context of the museum. To what degree does the museums complex context allow for a visitor to share the exact experience of ancient makers and users of the material objects we visit and study in the present? The material of ancient Egypt provides an effective means for analysing the museum experience as it has attracted an enormous range of interest beyond that of academia.[2] The 21st century museum visitor commonly gets a very simplistic, and often biased understanding of the experience of the individuals connected to these objects as a result of a lack of information known being shared for the visitor’s experience, as well as a lack of proper contexts and emphases.

Objects have an essential role in understanding the past as they have become the disciplinary mode of production as by immediate and tangible signs of their former associations.[3] Ingold puts forward two focuses in materiality; the raw and physical aspects, versus the social and historically situated agency of humans who project design and meaning onto such material.[4] The study of hermeneutics looks at interpreting the makers intentions through empathy and contextual information including the significance of actions, writing, institutions and products as a method to understand past experiences through artefacts.[5] Encountering the physical objects themselves can provide another perspective of a sensory experience, which can be deemed largely similar to those of the ancient Egyptians, yet the descriptions of such encounters are still very much based in present socially imbedded perceptions.[6] Despite the various theories put forth as to how one can best understand the past, we cannot be certain that all past individuals saw their relationship with their material world in the same way that we interpret it. Through a constructivist approach, the past cannot be perceived with complete objectivity.

The Visitor

Even in the study of archaeology, grasping past experiences is difficult and at times problematic, which becomes even more evident in the case of a museum visitor. When discussing the experience of the museum goer, it is important to define the different types of visitors that are included in this consideration. The visitor, in regard to Egyptian exhibits in particular, range from amateur enthusiasts, to academics, to specialists, and trained Egyptologists. All of these visitors come with their own biases in their perceptions, beliefs and previous experiences, while also being able to make their own choices on what to focus their visit on.[7] Visitors will always be biased by their own expectations and assumptions, and how much awareness a visitor may have of the interpretive theories previously discussed. Physical indicators of an object’s technical features, past life, and past meanings are also highly impactful on interpretations, all of which are not often highlighted to the visitor at the same time in the museum context. Furthermore, the nature of the museum is separated from the role of the visitor in that the ‘expert construction’ in the interpretation of an artefact is finalized by its presentation.[8]

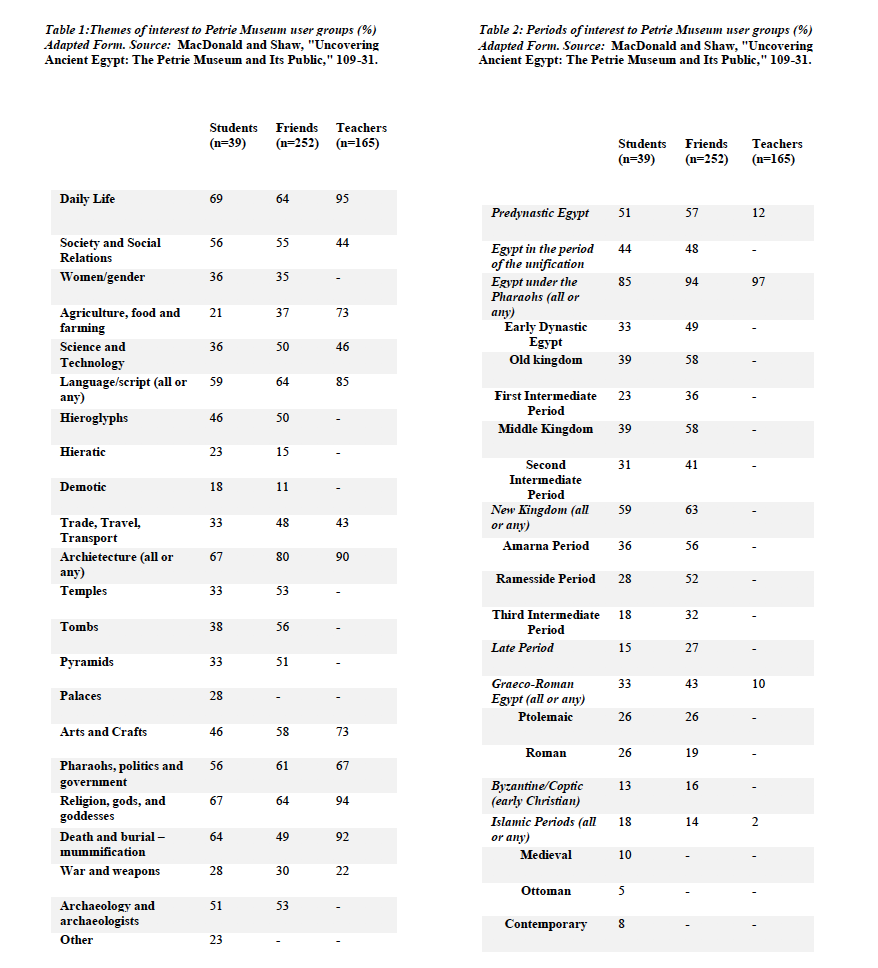

Fundamental to museum experiences is the central role the visitor plays in the presentation of these objects, as visitors can be viewed as a customer to the institution. As suggested by MacDonald and Shaw, the past is often idealised not to invite challenge but provide a leisure backdrop that will attract a paying public.[9] What is defined to be desirable in a collection changes over time as a result of the cultural milieu of the collectors and the demands of the visitors.[10] A study was completed of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London, England, to analyse visitor interests of different themes and periods (tables 1, 2). It is proven that there is not equal interest across all time periods of ancient Egypt and that there is emphasis on interests in themes that are not the most expressive of the producer’s experience or the user’s interaction with these objects beyond a funerary context. The funerary context for ancient Egyptians is one that closely mirrored their daily lives, yet it must be considered that as these objects were discovered in such contexts, this takes dominance in the story the object shares with present audiences. Furthermore, focusing on materials from the funerary context, disregards how individuals not represented in this context understood and interacted with such materials, which holds true for all past cultures studied.

The material from which we come to know individuals’ experiences is often categorized into specific time periods, as has been done in the study of visitors to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. This proves problematic being that the material of the past is not always and should not always be limited to such time periods that we have placed onto past societies. While one object may be attributed to a certain dynasty, the time in which such an object was made and used may be earlier or later than what has been ascribed to it. This is a simplistic way of viewing the complications of chronology that can be further complicated by drawing attention to the various periods of influence from each individuals cultural and spatial upbringing. These objects were not static, but rather as time passes, both the objects and people are transformed in ways that are interconnected.[11] As such, the museum context is one that hinders the ability to get at personal links that have been made with certain objects and their changing meanings, often providing more general descriptions of the materials they display.

The Museum

It is essential to also define the museum when considering the institutions impact on the interpretations being made by visitors. Museums have been deemed as the caretakers, documenters and educators of objects, who further decide how things are collected, categorized, defined and displayed.[12] The museum being initially a colonial institution brings with it problematic practices; this includes the habit of letting the objects speak for themselves as a means of measuring civilization within the necessary programs of improvement, paternalistic governance, social utility and economic factors.[13] While there are movements away from this, museums still collect and exhibit which are proficiencies of colonial practices, despite initiatives to reprimand this. With the practice of collecting at its core, the museum presents objects with a special aura of uniqueness separating it from ideas of the common or mundane.[14] In specific regards to ancient Egypt, it is also significant to acknowledge that this aura of exceptionality is also related to the fact that materials available to showcase are largely of the elite nature, being that they are preserved to a greater degree than those of the lower strata of society.[15] Due to the organisation of the museum, the visitor gets a clear distinction of the different phases, whether the exhibit is organized chronologically or by object use, which can be both of positive and negative influence to the understanding of the past. By having the different phases presented in an obvious way, it becomes clear that what is being viewed is not the result of a single event or place in the past. In terms of ancient Egyptian material in the museum, Riggs proposes that it is either presented to be a natural phenomenon available for rational scientific study or an artificial wonder of great feats.[16] This misses the much-needed modes of enquiry and self-reflectivity that is fundamental to understanding the individuals behind the objects.

Looking at ancient Egyptian Material Types

Significant to the interpretations of past experiences of the material world is the type of museum in which these objects are put on display. Many ancient Egyptian artefacts are received as pieces of art, as museums throughout time have had difficulty with placing Egypt into categories of Western knowledge due to a clear difference in worldviews between cultures. This is made clear in the case of the Hawara mummy portraits from Petrie’s collections at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, which were noted to have a perceived affinity to easel paintings of Renaissance and later European contexts.[17] These panels showcase the artistic stylings of the Graeco-Roman world as such panel paintings would not have survived in as good condition in the Greek and Roman environments, and as such do provide great artistic understanding for these cultures. However, this neglects the role of these portraits for the individuals that created and used them in Egypt during the Roman Period. It is the context of these portraits within Egyptian burials that allow for a better understanding in how they were used to adhere to the traditional practices and beliefs of the Egyptian afterlife. The presentation of these panels as simply artworks disregards their demonstration of the multicultural society in Egypt at the time, and the conceptual importance of their use as adaptions to pharonic burial face coverings. In considering all of the portraits uncovered throughout Egypt, these objects also speak to the to the diversity of existing styles that were available to the inhabitants of Egypt regionally, and as a matter of choice.[18] These items were initially divorced from their original context and understood and displayed within the discourse of art being exhibited at the National Gallery in London, having significant impact on the responses they generated from visitors.

Hawara Mummy Portrait

©2015 University College London. This work by the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology is licensed under the CC BY-NC-SA license.

It has been argued that within a piece of art one can get at the religious, metaphysical, political and economic tendencies of the epoch, which further represents the activity of the human mind.[19] As such, the classification of collections and objects within museums has a crucial influential role in the construction of meaning. It is still important to remember a work of art “cannot be understood in its windowless totality merely by an accumulation of knowledge about its circumstances of creation or by comparison with other objects of its time with which it will, inevitably, have superficial similarities.”[20] The ways that material culture of ancient Egypt have been presented over time contributes to the present conceptualisations of these past peoples, as it fuels assumptions and adds to the experiences of modern museum visitors.

This can be further explored through the discussion of Egyptian statues, being that in some cases there is very little distinction between the statue and the deity represented; an ideology rooted in ancient Egyptian ideas of divine embodiment and material manifestation.[21] Through presentation a crucial aspect of these objects can be lost to the visitor in the museum, especially within the context of an art exhibit, which ultimately misses the nature of these statues in ancient Egypt. There is also the question of the distinction between the makers and users of these statues, as it is not necessarily the straightforward divide that one would expect. The artisans of ancient Egypt have attributed the act of making to enlivening the statue of the deity, and the ‘users’ of such statues, being those who interacted with them, would participate in ritual practices where the statues were treated as persons.[22] Furthermore, the maker was not always separate from the user, as noted in the case of Nebwawy the high priest of Osiris whose duties as sculptor and priest overlapped in the act of sculpting, as creating was in itself a ritual.[23] Even if this complex relationship is described in brief description panels or other forms of tour guides, the personal attachment of individuals to certain deities and their interactions with these statues are lost to the exhibit visitor, especially since the statue is in a completely different context than where it would have been interacted with. While it has been argued that art objects extend their makers or users agency, one must remember that these statues were not seen as strictly art objects in their context as part of the ancient Egyptian material world.[24]

Posing Like an Egyptian

Individuals are not mindless users of a system but also realise the structure and transform the system through the ways they negotiate meaning in their individual purposes.[25] This stands true for both the museum visitor and ancient Egyptians. While visiting the museum exhibit allows for a visitor to interact with the material evidence of the past counterbalanced by the textual forms of evidence available, not all visitors are educated on these other modes of understanding past experiences and may not be trained with the skills needed to make suitable interpretations. Objects are not simply representations of individuals but are also constitutive of them as well.[26] This is not something that is effectively presented within all museum contexts or for all visitor types. While after viewing the splendours that are showcased to represent ancient Egypt, today’s museum visitor may exclaim, ‘look at me, I’m walking like an Egyptian,’ they do not truly understand what it would be like to walk in the footsteps of the individuals behind the collections exhibited. This is something that is difficult to grasp in both the museums representations and studies of ancient Egypt taking place. Though it is difficult, it should never be overlooked. How this aspect can enrich one’s experience to interreacting with material of the past is something that the world of material culture, especially within the museum, needs to work on making more accessible for all.

End Notes

[1] Lynn Meskell, Object Worlds in Ancient Egypt: Material Biographies past and Present, (Oxford: Berg, 2004), 55.

[2]Stephanie Moser, "Reconstructing Ancient Worlds: Reception Studies, Archaeological Representation and the Interpretation of Ancient Egypt," 1263-308.

[3] Meskell, Object Worlds in Ancient Egypt: Material Biographies past and Present, 218.

[4] Tim Ingold, Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture, (London: Routledge, 2013), 27.

[5] Raymond Corbey, Robert Layton, Jeremy Tanner, “Archaeology and Art,” In A Companion to Archaeology, edited by John. L. Bintliff (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004), 362; Michael Shanks, Experiencing the past: On the Character of Archaeology (New York: London: Routledge, 1991), 44.

[6]Joanna Brück, "Experiencing the Past? The Development of a Phenomenological Archaeology in British Prehistory," 45-72.

[7] Moser, "The Devil Is In the Detail: Museum Displays and the Creation of Knowledge," 22-32; MacDonald and Shaw, "Uncovering Ancient Egypt: The Petrie Museum and Its Public," 109-31; Copeland, “Constructing Pasts: Interpretation of the Historic Environment,” 83-95.

[8] Copeland, “Presenting Archaeology to the Public,” 132-44.

[9] MacDonald and Shaw, "Uncovering Ancient Egypt: The Petrie Museum and Its Public," 109-31.

[10] Akin, “Passionate Possessions: The Formation of Private Collections,” 114-24; Riggs, “Ancient Egypt in the Museum: Concepts and Constructions,” 1129-53.

[11] Gosden and Marshall, "The Cultural Biography of Objects," 169.

[12] Boast, “Neo-colonial Collaboration: Museum as Contact Zone Revisited,” 56-70; Riggs, “Ancient Egypt in the Museum: Concepts and Constructions,” 1129-53.

[13] Akin, “Passionate Possessions: The Formation of Private Collections,” 122; Boast, “Neo-colonial Collaboration: Museum as Contact Zone Revisited,” 64.

[14] Lynn Meskell, Object Worlds in Ancient Egypt: Material Biographies past and Present, (Oxford: Berg, 2004), 198.

[15] Lynn Meskell, and Rosemary A. Joyce, Embodied Lives: Figuring Ancient Maya and Egyptian Experience, (London: Routledge, 2003).

[16] Riggs, “Ancient Egypt in the Museum: Concepts and Constructions,” 1152.

[17] Riggs, “Ancient Egypt in the Museum: Concepts and Constructions,” 1129-53.

[18] “Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accessed September 25, 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/press/exhibitions/2000/ancient-faces-mummy-portraits-from-roman-egypt.

[19] Schwartz, "Walter Benjamin’s Essay on Eduard Fuchs," 106-22.

[20] Schwartz, "Walter Benjamin’s Essay on Eduard Fuchs," 120.

[21] Lynn Meskell, Object Worlds in Ancient Egypt: Material Biographies past and Present, (Oxford: Berg, 2004), 90.

[22] Lynn Meskell, Object Worlds in Ancient Egypt: Material Biographies past and Present, (Oxford: Berg, 2004), 98.

[23] Lynn Meskell, Object Worlds in Ancient Egypt: Material Biographies past and Present, (Oxford: Berg, 2004), 105.

[24] Corbey, Layton, Tanner, “Archaeology and Art,” 357-79.

[25] Corbey, Layton, Tanner, “Archaeology and Art,” 357-79.

[26] Lynn Meskell, and Rosemary A. Joyce, Embodied Lives: Figuring Ancient Maya and Egyptian Experience, (London: Routledge, 2003) 10.

Works Cited

Akin, Marjorie. “Passionate Possessions: The Formation of Private Collections.” In Learning

from things: method and theory of material culture studies, edited by William David Kingery, 114-24. London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996.

“Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Accessed September 25, 2020.

https://www.metmuseum.org/press/exhibitions/2000/ancient-faces-mummy-portraits-

from-roman-egypt.

Beard, Mary. "Souvenirs of Culture: Deciphering (in) the Museum." Art History 15, no. 4

(1992): 505-32.

Boast, Robin. “Neo-colonial Collaboration: Museum as Contact Zone Revisited.” Museum

Anthropology 34, no. 1 (2011):56-70.

Brück, Joanna. "Experiencing the Past? The Development of a Phenomenological Archaeology

in British Prehistory." Archaeological Dialogues 12, no. 1 (2005): 45-72.

Copeland, Tim. “Constructing Pasts: Interpretation of the Historic Environment.” In Heritage

interpretation, edited by Marion Blockley and Alison Hems, 83-95. London: Routledge,

2006.

Copeland, Tim. “Presenting Archaeology to the Public.” In Public Archaeology, edited by Nick

Merriman, 132-44. London: Routledge, 2004.

Corbey, Raymond, Robert Layton, and Jeremy Tanner. “Archaeology and Art.” In A Companion

to Archaeology, edited by John. L. Bintliff, 357–79. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004.

Gosden, Chris, and Marshall, Yvonne. "The Cultural Biography of Objects." World

Archaeology 31, no. 2 (2010): 169-78.

Ingold, Tim. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge,

2013.

Jeffreys, David. “Regionality, cultural and cultic landscapes.” In Egyptian Archaeology, edited

by Willeke Wendrich, 102-18. Chichester, UK and Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

MacDonald, Sally, and Shaw, Catherine. "Uncovering Ancient Egypt: The Petrie Museum and

Its Public." In Public Archaeology, edited by Nick Merriman, 109-31. London:

Routledge, 2004.

Meskell, Lynn., and Rosemary A. Joyce. Embodied Lives: Figuring Ancient Maya and Egyptian

Experience. London: Routledge, 2003.

Meskell, Lynn. Object Worlds in Ancient Egypt: Material Biographies past and Present. Oxford:

Berg, 2004.

Moser, Stephanie. "Reconstructing Ancient Worlds: Reception Studies, Archaeological

Representation and the Interpretation of Ancient Egypt." Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 22, no. 4 (2015): 1263-308.

Moser, Stephanie. "The Devil Is in the Detail: Museum Displays and the Creation of

Knowledge." Museum Anthropology 33, no. 1 (2010): 22-32.

“Mummy Portraits.” The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology UCL. Accessed September

26, 2020. http://petriecat.museums.ucl.ac.uk/detail.aspx?parentpriref=

Riggs, Christina. “Ancient Egypt in the Museum: Concepts and Constructions.” In A Companion

to Ancient Egypt, edited by Alan B. Lloyd, 1129-53. West Sussex; Malden, Mass: Wiley-

Blackwell, 2010.

Schwartz, Frederic. "Walter Benjamin’s Essay on Eduard Fuchs." In Marxism and the History

of Art, edited by Andrew Hemingway, 106-22. London: Pluto Press, 2006.

Shanks, Michael. Experiencing the past: On the Character of Archaeology. London; New York:

Routledge, 1991.