Curating Controversy:

Addressing the Theodore Roosevelt Statue

MaryKate Smolenski

Citation: Smolenski, MaryKate. “Curating Controversy: Addressing the Theodore Roosevelt Statue.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, September 25, 2020. https://cmsmc.org/publications/curating-controversy.

Abstract: The Theodore Roosevelt Statue outside the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City has long been a site of protest. Viewed as a symbol of white supremacy, the Roosevelt Statue depicts the former president high on a horse, literally raised above a Native American and an African. In 2018, a Mayoral Commission reviewed the work and the Mayor decided that the statue was to remain, but additional context was needed. The AMNH created an exhibit entitled Addressing the Statue. Following the 2020 protests regarding systemic racism in the United States, the museum and mayor finally decided to remove the sculpture. This article explores how the creation of AMNH, the creation of the field of anthropology, and Theodore Roosevelt’s life provide context about the statue and why it is associated with white supremacy. A brief overview is also given of the history of protests surrounding it, the Mayoral Commission, and the creation of the Addressing the Statue exhibition. The exhibition was flawed but began a further discussion about the sculpture. However, the 2020 protests confirmed to the museum and mayor that this controversial statue must go. The Roosevelt statue reflects the power of material culture and the visible legacy of white supremacy.

Key words: Anthropology, Cultural Evolutionary Theory, Racial Hierarchy, American History, Public History, Museum Studies, Imperialism, Colonialism, Systemic Racism

James Earl Fraser, Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt, 1940, Bronze

Image courtesy of the author

In 1940, the Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt was unveiled to the public on the steps of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City. The bronze statue was part of a larger New York State memorial to President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, who was formerly governor of the state, then served as president from 1901 to 1909. The statue is owned by the state but intimately connected with the AMNH. Architect John Russell Pope commissioned James Earl Fraser to design the equestrian statue of Roosevelt.[1] The statue is the first object viewed by visitors as they climb the main steps to the museum. One sees Teddy high above on a noble steed; the artwork’s hierarchical scale literally raises him above his companions, a Native American and an African. Sculptor Fraser intended the Native American and the African to be allegorical figures of the continents where Roosevelt hunted, Africa and North America, and stated that they would stand for, “Roosevelt’s friendliness to all races.”[2]

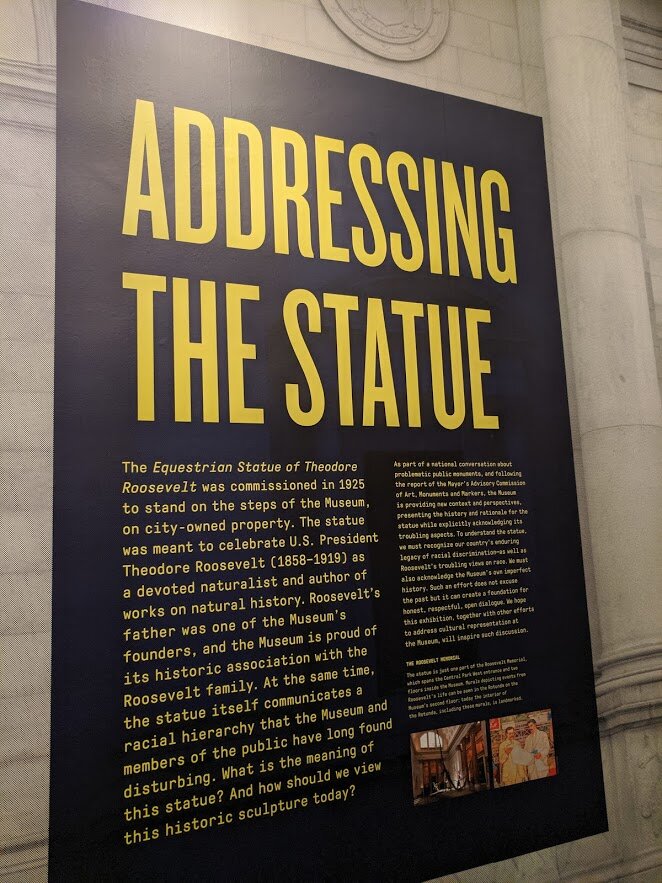

This statue has been the flashpoint of controversy and protests for decades. In 2018, a NYC mayoral commission examined the piece but was unable to reach a consensus on whether the sculpture should be removed, remain, or receive additional context. They presented these options to the Mayor, who ultimately ruled that the statue would not be removed, but that additional context and research was needed. This context resulted in an exhibit entitled Addressing the Statue, which opened in July 2019 at the AMNH. The exhibit was flawed but was the start of a dialogue. The Roosevelt statue is reflective of how powerful material culture can be. More than a statue, many view it as a visible symbol of white supremacy. While the statue remained after the Mayoral ruling in 2018, the 2020 protests regarding systemic racism in the United States lead to the museum and mayor agreeing to remove the sculpture. The statue is part of a problematic narrative of white supremacy and its history and context needs to be examined. This article will explore the statue’s creation and controversy along with the 2018 decision to keep the statue, the subsequent exhibit’s attempt to provide context, and the ultimate decision to remove it.

The world in which the statue was created

To understand the statue, one needs to look further back at the creation of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), the creation of the field of anthropology, and Theodore Roosevelt’s life. The American Museum of Natural History was established in 1869, when Albert Smith Bickmore, a student of zoology, proposed that a museum of natural history be created in New York City.[3] Bickmore was supported by several connected, wealthy, and white New Yorkers, including J.P. Morgan and Theodore Roosevelt Sr., the father of President Theodore Roosevelt; the charter of the museum was even signed in Roosevelt Sr.’s home, connecting the younger Roosevelt to the early beginnings of the museum.

The museum became a center for early anthropology, which focused a great deal on comparing different groups of humans. Early anthropologists started grouping people in terms of “race.” Race is not biological fact, but rather a social construct that has changed over time.[4] During the early years of anthropology, white men associated certain factors (height, skin color, head shape and size) with “races” that were then often associated with cultures. In 1871, anthropologist Edward B. Tylor defined culture as, “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, law, morals, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.”[5] Tylor’s work Primitive Culture promoted the idea of cultural evolution, which placed different cultures on a hierarchical ladder, and other anthropologists adopted this notion as well. Naturally, Western white men, such as Tylor, placed their societies at the apex of the later, referring to themselves as “civilization,” with darker skinned cultures/societies at the bottom of the hierarchy.[6]

Theories like Social Darwinism and eugenics developed to support these hierarchies. Social Darwinism applied the notion of “survival of the fittest” to society; it justified the societal power of certain people with the idea that they were inherently better.[7] Eugenics concerned the controlling of human procreation to breed people with desirable traits and prevent “undesirable” people from reproducing; this was later utilized as justification for genocidal and discriminatory practices by many, including the Nazis. “Undesirables” included non-Western and non-white groups, but also groups like Eastern Europeans, Southern Europeans, and the Irish.[8] White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (sometime referred to as “WASP”) were considered the apex of the cultural evolutionary ladder; anthropologist Tylor utilized religion as a deciding factor for rank on the evolutionary scale. Tylor himself was a white British Quaker.

Anthropologists and scholars of related disciplines began representing these problematic notions about human difference to the public, including through the utilization of museums like the AMNH. The AMNH was run by powerful, white men who presented these notions to the public as authorities on this “science.” The ideas of Social Darwinism, eugenics, and cultural evolution and their subsequent promotion by white men occurred at the same time as waves of new immigrants came into the United States and as the country rapidly industrialized.[9] American society was changing, and many of the museum’s trustees and leaders were fearful for the disappearance of their known world, and (with that) their dominance of said world. From 1880 to 1930, the museum was involved in global expeditions, ranging from discovering the North Pole to penetrating the jungles of the Congo. This was part of a vast public education and research program promoted by the museum, in which researchers who were employed by the AMNH contributed data towards the idea that certain people were inferior to others.

One noteworthy researcher was Frederic Ward Putnam, curator of the Department of Anthropology at AMNH from 1894 to 1903.[10] Putnam was a major proponent of cultural evolutionary theory. He was hired to be the chief of the anthropology department at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 and designed the ethnographical exhibit where cultures were displayed as different stages of evolution.[11] The darker skinned cultures were placed at the beginning of the fair’s Midway. As visitors walked along, they would see lighter and lighter skinned peoples, or the “advancement” in the “evolution” of man. Visitors would end up in the “White City” where the main exhibitions of Western society were and where all the buildings had white facades. After this display, the AMNH offered Putnam a position at the museum, thrilled by his views on cultural evolution, and Putnam accordingly shaped the department and the museum with his views.

While anthropology developed, Theodore Roosevelt promoted American imperialism in the 1900s. He helped colonize many areas for the United States, including the Philippines. Roosevelt used anthropology, world fairs, and the AMNH to promote his political ideas. After conquering the Philippines, he wanted the U.S. to colonize it and one of his justifications was that it was the United States’ duty to “civilize” the Filipinos. In fact, he intervened at the 1904 World’s Fair Exposition and, “the president demanded that short trunks replace the native loincloths worn by the Igorots and the Negritos.”[12] Roosevelt did not want the Filipinos presented as “complete barbarians” because then the public who believed in cultural evolutionary theory may have thought that Filipinos were incredibly low on the hierarchical scale and could not be “saved.” The president wanted to present them as an evolving, not static, group that could be “helped” by colonization. Roosevelt’s ideas of cultural evolution and politics went hand in hand at the fair and also at the museum. He himself assisted in the creation of the AMNH and went on many expeditions collecting specimens.[13] In fact, some of his finds from his youth were part of the museum’s earliest collections.

Both Roosevelt and the AMNH were involved in the eugenics movement, and the museum hosted two conferences with accompanying exhibits in 1921 and 1932.[14] Roosevelt also focused on conservation and creating the national parks, which is what he is often best remembered for. However, the creation of many of the national parks involved the removal and evacuation of native groups.[15] He was known for saying, “that only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of 10 are, and I shouldn't like to inquire too closely into the case of the 10th.”[16] This was the era of “Manifest Destiny” as well as segregation and “separate but equal.” Roosevelt had specific views about what type of people were superior and would lead civilization forward.

Earlier Protests about the Statue and the NYC Mayor’s Commission

The Roosevelt statue has been a site of protests for decades since many view the statue as one of the most visible symbols of white supremacy in New York. One notable incident occurred in 1971 when six Native Americans were arrested after they splashed buckets of red paint on the statue. Over the years, protests surrounding Columbus Day have focused on the statue as a symbol of white supremacy and colonialism. For example, in 2016, over 200 protesters arrived at the AMNH and demanded that the statue be taken down; these protesters were activists from the group Decolonize This Place. They offered an Anti-Columbus Day Tour with ten stops in the museum that highlighted white supremacy and colonialism in the institution’s displays and history.

Protests surrounding the statue have also been tied to the recent wave of statues and monuments being torn down or vandalized without authorities’ permission. Similar to the well-known 1971 act, the anonymous Monument Removal Brigade threw blood-like red paint onto the base of the statue in October 2017.[17] In that same year, NYC’s mayor, Bill de Blasio, established a commission to evaluate several controversial statues and memorials, including the statue of Roosevelt. This commission grew out of the protests and ultimately examined four sites: the Dr. J. Marion Sims Monument, a Marker for Marshal Philippe Pétain, the Christopher Columbus Monument, and the Roosevelt statue.

In its ruling on the Roosevelt statue, the Commission utilized historical documents alongside expertise from a variety of fields, which included art history, American studies, and the history of race and the eugenics movement. They allowed the public to submit their commentary through an online survey and set up five public forum meetings in the five boroughs. The public response reflected that the “monument has been subject to sustained adverse public reaction for many decades.”[18] The committee deliberated and sought to balance the historical perspectives with contemporary readings of aesthetics and the location of the statue. Many on the commission saw the statue “inextricably linked to AMNH.”[19] Some argued for the aesthetic value and skill of the sculpture while others saw the monument as an image of cultural evolutionary theory and racial hierarchy. The commission also considered the original intentions of the artist.

The commission was unable to reach a consensus about this statue. There was a debate between members; some wanted to recognize the significance of Roosevelt as a major figure in American history. Many commission members thought that more exact information about the statue would help the public understand Roosevelt’s mixed and complicated legacy. Others in the commission, “did not agree that more information would impact the viewing public’s experience of the form of the sculpture, which they consider to be a racist work of public art.”[20] Those opposed to the statue thought there was enough scholarship that supported a decision to relocate the monument. Opinions were divided across three recommendations. Most members were separated into two camps. Half believed “that additional historical research is necessary before recommendations can be offered.”[21] The other half advocated:

to relocate the sculpture. Within this group there was a diversity of opinion regarding where and how relocation should occur, and options considered include relocation [1] within the larger Theodore Roosevelt complex, [2] inside the AMNH, [3] to another publicly accessible location so that the monument’s prominence and impact on a diverse viewing public are reduced, or [4] re-contextualize within an existing and/or historic collection preferably on City property.[22]

As for the third option, a few members thought that the monument should stay but that there should be additional on-site signage or interventions to provide context. For this option, the goal “would be to re-think how the statue is presented, to frame it in a way that discloses the historical distance we have traveled from once-popular ideas.”[23] In 2018, the Mayor decided that the addition of more context was needed and left open the possibility of adding new artwork. Following the commission’s report, protests continued.

On October 10, 2018 (Columbus Day or Indigenous Peoples Day), Decolonize This Place once again led hundreds gathered at the AMNH to take part in a protest.[24] Protesters gathered inside the museum with signs and chants; they dispersed throughout the exhibits to highlight colonialism, racism, sexism, and dehumanization in the museum. The protesters had several demands including:

renaming Columbus Day 'Indigenous Peoples Day'; removing the Theodore Roosevelt statue outside the museum; repatriating human remains and sacred artifacts; convening a public meeting to hear testimony on how the museum has harmed people; and putting together a committee to “oversee a decolonization process at all city museums that enjoy subsidies through taxpayer support.”[25]

The group then proceeded outside to the Roosevelt statue, which was guarded and heavily barricaded by the NYPD. Despite the barricades, they rallied near the statue, displayed banners, and stated their demands.

Museum leadership and Decolonize This Place did meet. The museum’s senior director of communications stated the museum is committed to working on cultural representation issues, including, “working on a complete renovation and reinterpretation of the Northwest Coast Hall. That work, along with the Stuyvesant Diorama context project, is part of a series of things that the Museum is doing to address aspects of our halls that are out of date."[26] Representatives from the activist group stated that the museum agrees with them but that the museum insists on going at their own slow pace. Amin Husain of Decolonize This Place stated, “we keep telling them, children are mandated to come to this museum to learn and you say you’re against white supremacy, but everything you do indoctrinates it without even saying what it is.”[27]

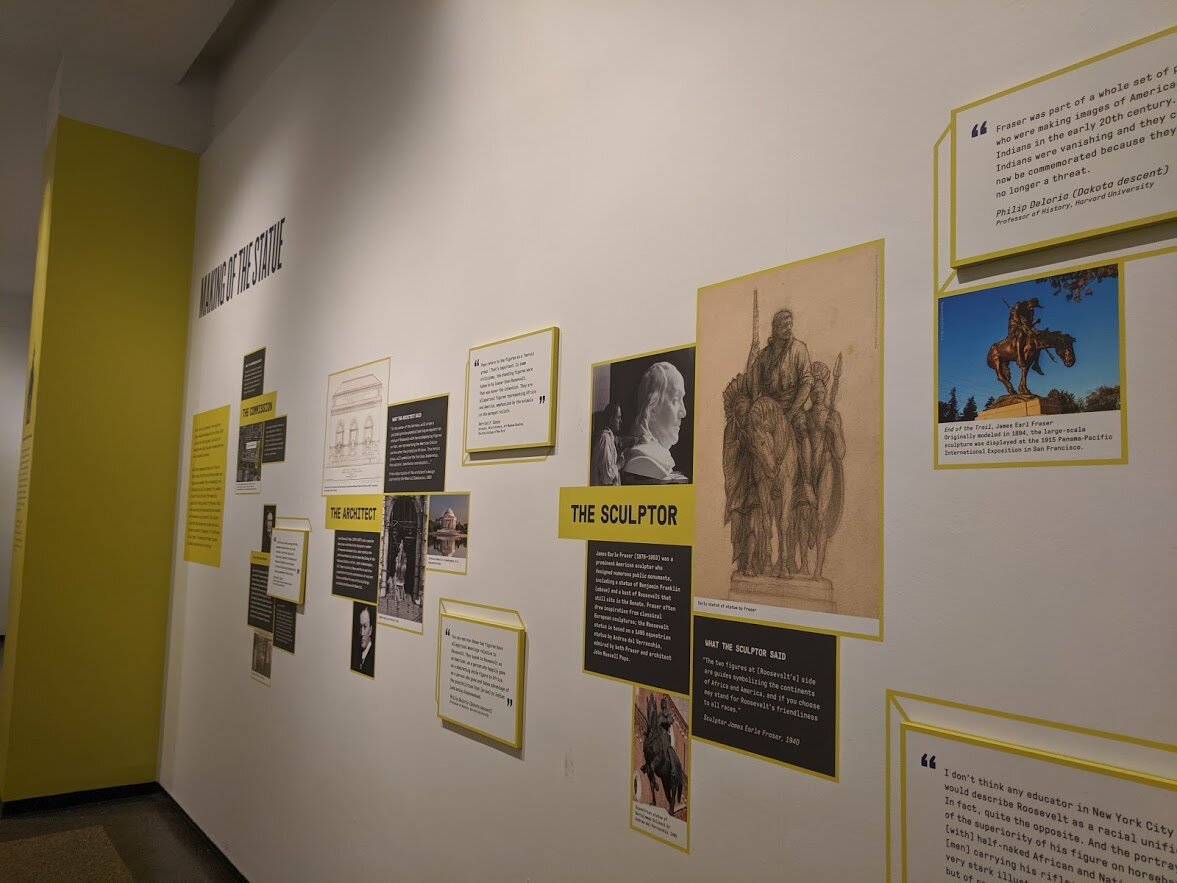

“Addressing the Statue” Exhibit

With the Mayor’s decision, the AMNH opted to create an exhibit inside the museum about the statue and its controversy. The exhibit is temporary; however, the AMNH did state that it is looking for other ways to incorporate parts of it in other areas of the museum.[28] The video included in the exhibit is also available on the museum’s website. Drawing on multiple perspectives, including artists, scholars, and visitors, the video entitled “The Making of a Monument” discusses Theodore Roosevelt’s accomplishments and flaws. The perspectives displayed in the video are split, as the Mayoral commission was, on what to do with the statue—should it remain or be taken down. The representation of diverse opinions shown confirms the success of the museum providing the public with more information. This exhibit explores the history of the statue’s design, installation, and responses to it. The AMNH admits their own complicity at some points of the exhibit, admitting to their involvement in the eugenics movement. The exhibit also explores who the two men depicted in the statue with Roosevelt may represent and discusses the lives and experiences of modern Africans and Native Americans, demonstrating they are not extinct groups but living, breathing people and communities striving for more appropriate representation today. Museum representatives stated that this exhibit shows the museum will not cover up its past and that they welcome dissent.

The museum hopes visitors will identify with some of the presented views while also hearing from different perspectives. Ms. Halderman, the AMNH’s vice president for exhibition, stated that the exhibit is “not really about us providing the answer… it’s about us providing the springboard so that everybody else can take a look.”[29] The AMNH has also began to reconsider other displays with the same mentality; for example, their Stuyvesant or Old New York diorama contains stereotypes of Lenape leaders, but they have now added captions on the glass explaining why the diorama is offensive. Ms. Futter, the museum’s president, states, “People used to walk by that diorama and pay absolutely no attention to it… now, they are stopping, they are reading it, and it’s having a high impact.”[30] However, some believe that the new exhibit is not enough. Mabel O. Wilson is a critic of the exhibit and also served on the mayoral commission. She voted to move the statue elsewhere. Dr. Wilson, who teaches architecture and African American and African diaspora studies at Columbia, believed that the exhibit was a starting point for both visitors and the museum. Dr. Thomas of the AMNH states that, “It’ll never be enough, but maybe it can kind of keep this going…Fifty years from now, who knows where that’s going to be?” [31] The exhibit was the start of a conversation.

However, the exhibit certainly has flaws. First off, the museum was not proactive in admitting their complicated past and it took many years, protests, and a recommendation from the mayor for the museum to address the controversy of the statue. Moreover, roughly half the video discusses Roosevelt’s merits, as there is still a desire to promote his achievements. One example that Douglas Brinkley mentioned was that Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington to the White House. Brinkley stated that, “never before an African American sat in the White House, and T.R. got hammered for this.”[32] While Washington was an advocate for the Black community, he was often dismissed by other Black leaders, such as W.E.B. DuBois, for his less than radical stances. Washington urged African Americans to accept discrimination for a time and concentrate on elevating themselves through self-help and racial solidarity. Roosevelt picked an African American leader who was less likely to change the status quo for white supremacy; the video merely highlighted that Roosevelt consulted with Washington, providing no context on Washington’s stances.

Furthermore, much more could have been said about Roosevelt’s involvement in imperialism and discussion of the world that he was living in, covered in prior sections, could have been incorporated more. The film and exhibit should have provided more context about the role of anthropology and the museum itself in cultural evolutionary theory and racial hierarchy. Instead the museum shies away from much of this, only discussing that the museum held two eugenics conferences. The exhibit stated that, “we must acknowledge the museum’s own imperfect past,” but little was done to implicate the museum.[33] There was minimal discussion of how the museum’s research and displays helped institutionalize, promote, and provide scientific data for this racial hierarchy displayed in the statue.

2020 Protests and the Decision to Remove

Addressing the Statue was open for less than eight months when the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York City and the AMNH closed its doors to the public. On May 25, 2020, George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis; outrage over his death, captured on video, sparked unrest and protests all over the United States, including New York City. Protests began to expand to larger issues of systemic racism, colonialism, and white supremacy. As symbols of oppression, statues and public monuments to Confederate soldiers and other controversial figures, ranging from Christopher Columbus to Edward Colston, began to topple. Once again, the controversial Teddy Roosevelt statue, a visual emblem of white supremacy, came under fire. On June 13, the Roosevelt statue was covered in paint.[34]

Museums publicly responded to protests and addressed their own complicity in perpetuating white supremacy and systemic racism, which is intimately connected to the history of museums and the United States’ involvement in slavery, colonization, and imperialism. Systemic racism refers to structures and systems, like healthcare or education, that create and perpetuate inequity for people of color. On June 21, 2020, the AMNH released a statement that the museum was moved by the demands for racial justice and watched as the narrative turned to statues and monuments as “powerful and hurtful symbols of systemic racism.”[35] The AMNH indicated that the statue was intended to celebrate Roosevelt’s achievements in natural history, but admitted that the statue “communicates a racial hierarchy that the museum and members of the public have long found disturbing.”[36]

The statement discussed the 2017-2018 Mayoral Commission that decided on additional context, which led to the creation of Addressing the Statue. The AMNH stated, “we are proud of that work, which helped advance our and the public’s understanding of the Statue and its history and promoted dialogue about important issues of race and cultural representation, but in the current moment, it is abundantly clear that this approach is not sufficient.”[37] The museum then went on to say that they have requested the city move the statue. Mayor Bill de Blasio’s office agreed to the removal, stating, “the city supports the museum's request. It is the right decision and the right time to remove this problematic statue.”[38]

The Addressing the Statue exhibition had shortcomings; it should have included even more context about the statue’s era of creation and the figure it represented, but it did start further dialogue about the problematic sculpture. However, the offending work remained outside, hundreds of feet away from this contextualization. The statue still loomed over visitors as they entered, displaying imagery of racial hierarchy—reflecting the world of cultural evolutionary theory and eugenics that it was created in, and reminding many of the systemic racism of today. Material culture has power, and visual symbols of white supremacy have a strong impact on many Americans. Decades of protests spoke out against the Teddy Roosevelt statue; after years of ignoring complaints and protests, there was an attempt at context, but the museum and city have finally admitted that this controversial statue must go.

Endnotes:

[1] John Russell Pope was a well-known architect of the era. He also designed the Thomas Jefferson Memorial, the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, the extension of the Frick Museum, and more.

[2] “Addressing the Theodore Roosevelt Statue: Special Exhibit | AMNH,” American Museum of Natural History, accessed November 14, 2019, https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/addressing-the-theodore-roosevelt-statue.

[3] “About the Museum,” American Museum of Natural History, accessed November 17, 2019, https://www.amnh.org/about.

[4] Staffan Müller-Wille, “Race and History: Comments from an Epistemological Point of View,” Science, Technology & Human Values 39, no. 4 (July 1, 2014): 597–606, https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243913517759; Robert W. Sussman, The Myth of Race: The Troubling Persistence of an Unscientific Idea (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014); Audrey Smedley and Brian D Smedley, “Race as Biology Is Fiction, Racism as a Social Problem Is Real: Anthropological and Historical Perspectives on the Social Construction of Race,” Am Psychol 60, no. 1 (2005): 16–26, https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.16.

[5] Edward Burnett Tylor, Primitive Culture (New York: J.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1920).

[6] Tylor.

[7] Lee Baker, “Ascension of Anthropology as Social Darwin,” in From Savage to Nero: Anthropology and the Construction of Race, 1896-1954 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998).

[8] Tylor, Primitive Culture.

[9] Donna Haraway, “Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908-1936,” Social Text 11 (Winter 1984): 20–64.

[10] Baker, “Ascension of Anthropology as Social Darwin.”

[11] Baker.

[12] Baker.

[13] Haraway, “Teddy Bear Patriarchy.”

[14] “Addressing the Theodore Roosevelt Statue”; “Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments, and Markers: Report to the City of New York,” January 2018.

[15] “Addressing the Theodore Roosevelt Statue.”

[16] “Addressing the Theodore Roosevelt Statue”; Julia Glum, “Vandals Attack ‘racist’ Theodore Roosevelt Statue in New York City with Blood Red Paint,” Newsweek, October 26, 2017, https://www.newsweek.com/theodore-roosevelt-statue-graffiti-nyc-museum-693590.

[17] Glum, “Vandals Attack ‘racist’ Theodore Roosevelt Statue in New York City with Blood Red Paint.”

[18] “Mayoral Advisory Commission.”

[19] “Mayoral Advisory Commission.”

[20] “Mayoral Advisory Commission.”

[21] “Mayoral Advisory Commission.”

[22] “Mayoral Advisory Commission.”

[23] “Mayoral Advisory Commission.”

[24] Ashoka Jegroo, “Photos: Hundreds Of Protesters Condemn Colonialism, Patriarchy, And White Supremacy At AMNH,” Gothamist, October 10, 2018, https://gothamist.com/news/photos-hundreds-of-protesters-condemn-colonialism-patriarchy-and-white-supremacy-at-amnh.

[25] Jegroo.

[26] Jegroo.

[27] Jegroo.

[28] Nancy Coleman, “Angered by This Roosevelt Statue? A Museum Wants Visitors to Weigh In,” The New York Times, July 15, 2019, sec. Arts, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/15/arts/design/theodore-roosevelt-statue-natural-history-museum.html.

[29] Coleman.

[30] Coleman.

[31] Coleman.

[32] “Addressing the Theodore Roosevelt Statue.”

[33] “Addressing the Theodore Roosevelt Statue.”

[34] Lily Goldberg, “Protesters Face Off In Front of Controversial Teddy Roosevelt Statue,” West Side Rag, June 28, 2020, https://www.westsiderag.com/2020/06/28/protesters-face-off-in-front-of-controversial-teddy-roosevelt-statue.

[35] “Addressing the Theodore Roosevelt Statue.”

[36] “Addressing the Theodore Roosevelt Statue.”

[37] “Addressing the Theodore Roosevelt Statue.”

[38] Hollie Silverman and Ganesh Setty, “Theodore Roosevelt Statue Will Be Removed from the Front Steps of the Museum of Natural History,” CNN, June 22, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/22/us/new-york-theodore-roosevelt-statue-removal-trnd/index.html.

Works Cited

American Museum of Natural History. “About the Museum.” Accessed November 17, 2019. https://www.amnh.org/about.

American Museum of Natural History. “Addressing the Theodore Roosevelt Statue: Special Exhibit | AMNH.” Accessed November 14, 2019. https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/addressing-the-theodore-roosevelt-statue.

Baker, Lee. “Ascension of Anthropology as Social Darwin.” In From Savage to Nero: Anthropology and the Construction of Race, 1896-1954. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998.

Coleman, Nancy. “Angered by This Roosevelt Statue? A Museum Wants Visitors to Weigh In.” The New York Times, July 15, 2019, sec. Arts. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/15/arts/design/theodore-roosevelt-statue-natural-history-museum.html.

Glum, Julia. “Vandals Attack ‘racist’ Theodore Roosevelt Statue in New York City with Blood Red Paint.” Newsweek, October 26, 2017. https://www.newsweek.com/theodore-roosevelt-statue-graffiti-nyc-museum-693590.

Goldberg, Lily. “Protesters Face Off In Front of Controversial Teddy Roosevelt Statue.” West Side Rag. June 28, 2020. https://www.westsiderag.com/2020/06/28/protesters-face-off-in-front-of-controversial-teddy-roosevelt-statue.

Haraway, Donna. “Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908-1936.” Social Text 11 (Winter 1984): 20–64.

Jegroo, Ashoka. “Photos: Hundreds Of Protesters Condemn Colonialism, Patriarchy, And White Supremacy At AMNH.” Gothamist, October 10, 2018. https://gothamist.com/news/photos-hundreds-of-protesters-condemn-colonialism-patriarchy-and-white-supremacy-at-amnh.

“Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments, and Markers: Report to the City of New York,” January 2018.

Müller-Wille, Staffan. “Race and History: Comments from an Epistemological Point of View.” Science, Technology & Human Values 39, no. 4 (July 1, 2014): 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243913517759.

Silverman, Hollie, and Ganesh Setty. “Theodore Roosevelt Statue Will Be Removed from the Front Steps of the Museum of Natural History.” CNN, June 22, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/22/us/new-york-theodore-roosevelt-statue-removal-trnd/index.html.

Smedley, Audrey, and Brian D Smedley. “Race as Biology Is Fiction, Racism as a Social Problem Is Real: Anthropological and Historical Perspectives on the Social Construction of Race.” Am Psychol 60, no. 1 (2005): 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.1.16.

Sussman, Robert W. The Myth of Race: The Troubling Persistence of an Unscientific Idea. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.

Tylor, Edward Burnett. Primitive Culture. New York: J.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1920.