A Marxist Approach to Ptolemaic Society: Through the Lens of the Maritime Industry

Ptolemaic Egypt has been studied by classical and archaeological perspectives but has limited its scope to Greco-Roman authors and material analysis which neglects the people. This article applies a Marxist approach created by the author to the archaeological material within the port city of Thonis-Heracleion. This review of the literary landscape of Ptolemaic Egypt suggests a Marxist approach to the archaeological material can show the underrepresented people within the maritime industry and display social groups, inequality, class relations, and modes of production. The material evidence of ships, anchors, weights, nails, faunal remains, and tools that yield evidence of the social dynamics of Thonis-Heracleion. Due to the pandemic, all of the materials are extracted from literary or online resources regarding each site. This approach was found to be stringent but worked, to an extent, within the evidence gathered. Despite, understanding the history, aspects, and application of the manufactured Marxist approach, the archaeological material can expand interpretive opportunities for future study in Ptolemaic Egypt.

“Take me Back to the Good Old Days”: Racism, Berlin Wool Work, and Comfort

Whether they be hung, worn, or used in a multitude of ways, textiles are a tangible component of material culture. They can tell us anything from political culture to stories of nostalgia.This 1876 Berlin wool table cover found in the collection of Winterthur Museum (2020.004) is a curious example of how embroidery and nostalgia intersect. This piece of textile, while overtly racist in its presentations, actually helps us consider the idea of racism in textiles as a teaching object. Even though the imagery of this piece is highly racialized and offensive, it was also evidently loved and cared for by its owners—enough so that the owner, or owners, came back multiple times to make alterations and preserve the piece. This paper discusses not only the tangible aspects of the table cover such as the stitches and design influences, but also the intangible such as what the designs in the cloth tell an audience. Given that many of the designs on this tablecloth were taken from children’s stories, the piece argues that this was intentional in order to “other” Black bodies and garner a certain type of racism—nostalgic racism. This racism is presented in this object via the space of the parlor. The parlor was no longer just a place to be with family and on special occasions, but quickly became one of the most radical forms of conspicuous consumption of the nineteenth century. It was a space to make a statement about how your family perceives the world and vice versa. While this piece might stoke immediate negative feelings, it is critical to remember that those were not the feelings experienced by the owner of this piece and their family. They saw these racist images as amusing and a cultivator for conversation and community.

Museum Orientalism:

Although museums that display from all over the world are commonplace in both Europe and North America, their histories are much more complicated than meets the average visitor’s eye. In fact, these “universal survey museums,” like the Louvre, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, are based upon Roman traditions of displaying war trophies. As such, the original purpose of such museums was to attest to the greatness of the modern nation-state, and consequently construe the history of art as the history of the highest European civilizations. Thus, these museum’s histories of collecting and exhibiting the arts of, for example, Asia or Africa requires critical consideration. Inspired greatly by Saidian Orientalism, this article describes and interprets how “East versus West” thinking and scholarship incorporated two early US American museums, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The East-West division influenced how both of these museums came to organize their administrations between experts on art history and experts on “the Orient.” Furthermore, Orientalized juxtapositions, a feature of Hegelian art historical theory popular at the time, formulated how museums organized their exhibition spaces. By following the museum’s gallery program, visitors enacted the evolution of civilization from Orient to Occident, and envisioned the differences between Western and Eastern arts as high and low respectively. This article primarily considers two juxtapositions: Greco-Roman traditions versus Egyptian traditions, and European paintings versus Oriental (East Asian) decorative arts. Part two of this article continues with the history of Orientalism at the MFA and the MET in the 1890s and 1900s. During this time, the both museums solidified the East-West binary as a part of their administrational structure and exhibition layout. Furthermore, museum engagements with East Asia led to the development of another Orientalized binary: East Asian crafts versus Western paintings.

Museum Orientalism:

Recent social justice and decolonial movements have led museums in Europe and North America to address the role they have historically played in maintaining imperial and white-supremacist hegemonies. Although museum scholarship has produced some important work on the history of museums as imperial, racist institutions, few scholars, if any, have attempted to understand the specific ways that Orientalism informed the early formations of the modern, encyclopedic museum of the West. Inspired greatly by Saidian Orientalism, this article describes and interprets how “East versus West” thinking and scholarship incorporated two early US American museums, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The East-West division influenced how both museums came to organize their administrations between experts on art history and experts on “the Orient.” Furthermore, Orientalized juxtapositions, a feature of Hegelian art historical theory popular at the time, formulated how museums organized their exhibition spaces. By following the museum’s gallery program, visitors enacted the evolution of civilization from Orient to Occident and envisioned the differences between Western and Eastern arts as high and low respectively. This article primarily considers two juxtapositions: Greco-Roman traditions versus Egyptian traditions, and European paintings versus Oriental (East Asian) decorative arts. Part one of this article argues that the representational nature of both Orientalism and universal survey museums warrants critical consideration of “East versus West” thinking in such museums and reviews the first two decades of these two museums’ histories regarding Orientalism as thought and a discipline, focusing on their endeavors with the ancient Middle East and Egypt.

Monstrous Women:

Horror, like fashion, appears to be an underestimated tool for understanding political and social change. Both subjects are habitually tossed aside as frivolous and senseless, yet, this article argues that both devices are approachable and digestible in a way that makes them significant. Women are often marginalized in film, a reflection of a larger social issue that manifests clearly in horror films where they are treated violently and exploitatively. This article investigates the costuming of women in a selection of horror films from the 21st century and how these costumes express and intensify the narrative by looking at the tropes of female monsters, specifically the maneater. This trope is associated with sexuality, whether through the overt use of seduction or sexual organs used as weapons. How do costumes in these films work with or against the current narrative of women in society? Exploring the film industry in this context is essential given the industry’s tendency to showcase public opinion in subtle or not so subtle ways. Ideas of the grotesque and its unquestionable connection to the female sex directly relate to these politics and social ideas, but also to horror storytelling and the mythology of monsters we observe throughout time.

Manufacturing Heritage:

Engaging the lenses of art history and cultural heritage studies, this article evaluates the history and functions of the Palazzo Strozzi, a Florentine Renaissance palace re-purposed into an exhibition space and research institution in the twentieth century. This paper addresses the pivotal role of the Fascist regime in the transformation of the building. This article considers the Strozzi’s history, as well as the gaps in the history presented by the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi’s website, and aims to create a more complete, complex picture of its role throughout the twentieth century. Ultimately, this paper suggests that aspects of the Palazzo’s history have been purposefully omitted, due to their irreconcilable political nature.

An Honest Day’s Work:

This paper serves as an exploration of the reliance of open world fantasy role-playing games on evoking emotions of pastoral romanticism in the player. Such games tend to be dominated by rural landscapes, and farming locations and objects often play a central role in the player’s interaction with the world. In particular, the paper will investigate mechanics where the player receives a personal stake in a pastoral setting, such as when a player-controlled hero spends significant game time engaging in farmhouse construction, food production, or other central aspects of rural life. It is in this aspect, the paper argues, that pastoral romanticism creates a significant player appeal entirely separate from the allure of heroic adventuring. Players of fantasy games take on the trappings of the aristocrats of ages past in their idealized engagement with otherwise taxing rural life, and similar to the early modern bourgeoisie, fantasize about escaping from the pressures of a modern industrialist lifestyle just as much as they fantasize about killing dragons. In absence of meaningful control over physical productivity in the real world, this progression towards a “perfect” rural landscape that one creates through shaping the land according to one’s wishes, is an appealing simulation of an activity not available to the average urban or suburban player. However, it simultaneously renders the same player a pseudo-aristocratic interloper into a fairytale version of working-class realities.

An Honest Day’s Work:

This paper serves as an exploration of the reliance of open world fantasy role-playing games on evoking emotions of pastoral romanticism in the player. Such games tend to be dominated by rural landscapes, and farming locations and objects often play a central role in the player’s interaction with the world. In particular, the paper will investigate mechanics where the player receives a personal stake in a pastoral setting, such as when a player-controlled hero spends significant game time engaging in farmhouse construction, food production, or other central aspects of rural life. It is in this aspect, the paper argues, that pastoral romanticism creates a significant player appeal entirely separate from the allure of heroic adventuring. Players of fantasy games take on the trappings of the aristocrats of ages past in their idealized engagement with otherwise taxing rural life, and similar to the early modern bourgeoisie, fantasize about escaping from the pressures of a modern industrialist lifestyle just as much as they fantasize about killing dragons. In absence of meaningful control over physical productivity in the real world, this progression towards a “perfect” rural landscape that one creates through shaping the land according to one’s wishes, is an appealing simulation of an activity not available to the average urban or suburban player. However, it simultaneously renders the same player a pseudo-aristocratic interloper into a fairytale version of working-class realities.

The Dual Life of Northwest Coast First Nations Masks in Western Institutions:

The museum frames our ideas about the livelihoods and person hoods of other people, as they are where the public encounters an other—a person different from who they identify as—often they have never met in their daily lives. Taking anthropologist James Clifford’s essay “On Collecting Art and Culture” as its departure, this paper argues that the traditional Western museum’s exhibition form cannot do justice to the histories and lives of non-Western objects, specifically masks from Northwest Coast Indigenous cultures, because the museum’s historical foundation was established by Enlightenment meta-narratives that counter the belief systems of many non-Western people, which reinforce stereotypes about the cultures the objects represent. The author presents three examples of exhibition forms that counter the Western model lifted from Clifford’s conclusion in 1988, demonstrating three distinct alternatives to forms that embrace Enlightenment principles, further oppressing the families and cultures to whom these items belong. The Nuyumbalees Cultural Center in Cape Mudge presents their sacred collection as alive and purposeful through programming and use of the big-house style building to provide a cultural and familial history of the objects and tradition of the potlatch. The Museum at Campbell River’s Treasures of Siwidi gallery activates a family’s contemporary collection of potlatch masks as keepers of history through an aural performance of the legendary narrative. The U’Mitsa Cultural Center’s virtual tour uses contemporary videos, 3D modeling, and language learning tools to animate the historical collection of masks from a variety of carvers and owners in a contemporary framework speaking to the interests of locals and global researchers. In order to create more inclusive, respectful, generative, and accurate display practices that honor the history of these items, museums must take steps to deconstruct the Enlightenment value systems upon which the Western Museum model was founded within their display practices.

Crafting Cottagecore :

This paper explores the internet aesthetic “cottagecore” – its historical origins and rise in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as its connection to craft. Cottagecore can be understood as the projection of the core fantasy of escape to a cottage in the woods to live as if it were a simpler time. As such, the desire to make things with one’s hands as a form of self-sufficiency-based self-care has become associated with cottagecore modes of production. This research considers this aesthetic act of making and its inherent digital engagement through the historical lens of the pastoral, Rousseau’s eighteenth- century romanticism, and William Morris’ nineteenth-century neo-Medievalism. The prime objective of this study is to investigate how cottagecore fits into this lineage, and to consider the implications of its digitization.

By examining activity, craft, and digital making, this research reckons with the inherent contradictions of cottagecore: its glorification of the rural idyll, the handmade, and a bucolic isolationism, as well as its coexistence with the technical, the distance from the material through the digital, and the interconnectedness of the internet. These contradictions manifest through social media platforms like TikTok, whereby the most popular of these acts are documented, produced, and circulated, and consumed as content, creating a continuous social loop of escapism. With these key concepts at the helm, this paper will emphasize the ever-growing intersection between production of material culture and the digital age.

Washington Rallying the Troops at Monmouth (1857):

Since the late-eighteenth century, artists have replicated and disseminated George Washington's image and likeness to preserve his memory and legacy. The popularization of history painting compelled artists to decorate a canvas with decisive moments in the country's founding years. Emanuel Leutze (1816-1868) is one such artist who won praise for his monumental Washington Crossing the Delaware in 1851. Two years later, Leutze created a companion piece, Washington Rallying the Troops at Monmouth (1853). This work shows an unfavorable side of Washington, a commander scrambling to catch his retreating troops. While the public and scholars often focus on Leutze’s more famous image of Washington, the companion piece offers a deviation from sacrosanct portrayals of the first president.

This article examines how David Leavitt commissioned Leutze to recreate this piece in 1857 for his daughter, Elizabeth Leavitt Howe. It argues that the shift in tonality speaks to its change in display, from a monumental canvas intended for a gallery, to the veneration of Washington's image as a form of emulation and active remembrance in a domestic domain. The gifting of the 1857 painting informs the cult of domesticity and code of household governance ever-present in American culture. The painting, therefore, becomes a material way to understand the relationship between objects and family members in nineteenth-century America. Through provenance research, visual analysis, and object networks, this piece will illuminate the divergence in Washington's iconography, while also highlighting the changes made for its placement in a nineteenth-century domestic domain.

The Performativity of Hair in Victorian Mourning Jewellery

Mourning rings were popular items of remembrance in the Victorian era which commonly incorporated the hair of a departed loved one. The role of hair within this type of jewellery is discussed in relation to performativity; a theory that has been successfully employed by a variety of fields to better understand the nature and effects of certain kinds of performance, particularly those that closely relate to the expression and construction of identity. The form of mourning rings, the processes involved in their construction and the messages they communicated to society are examined in reference to performativity, to ascertain the value of considering the mourning ring tradition within this theoretical framework. This article asserts that the processes involved in the construction of mourning rings were not merely representational but performative, as they both symbolise and create transitions between conventional states. Moreover, mourning jewellery was an invented tradition within the larger culture of performative mourning, that addressed the need to reconstruct gendered class identities in the wake of profound social change.

Cambodian Artistic Resilience:

Museums are among the different agencies available to help people better themselves. One museum that strives to do this is the Cambodia Peace Gallery (CPG), located in Battambang, Cambodia. It was established in 2018 by the Center for Peace and Conflict Studies (CPCS) by Cambodian native and Khmer Rouge (KR) genocide survivor, Soth Plai Ngarm. The CPG strives to tell a story of Cambodian resilience and achievement, despite a longstanding conflict history. Through gallery exploration, genocide survivors are meant to experience trauma recovery by facing emotions they are typically told to suppress in their face-saving culture. All museum efforts are driven by a desire to showcase Cambodia’s dynamic story in a way that inspires visitors to become actors for peace. The CPG’s mission of informing the public about peace and how to get there ultimately encourages healing from the KR genocide (1975-1979). One of the most recent exhibits the CPG has committed itself to explores refugee camp-based grassroots efforts founded to preserve poignant parts of Cambodia’s cultural identity. Specific performing arts of this nature are demonstrated in the work of past royal ballet dancer, Van Savay, whose work is captured by American photographer, Sharon May. Relief efforts are also manifested in the social enterprise of Phare Ponleu Selpak (PPS). In collaboration with May and PPS, the CPG’s exhibit explores how the reintroduction of Khmer arts has linked creative expression, identity healing, and hope for the future. Most importantly, the rebirth of art and culture has allowed Cambodians to imagine a future for their country. By presenting this information, the museum’s agency will advance the work started in the refugee camps and promote sustained present-day resilience.

A Portrait of Death

This article delves into the topics of medieval tomb sculpture in Europe, memento mori spirituality in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, portraiture, the Black Death and Roman Catholic response, and the complex relationship between the living and the dead. By introducing medieval tomb sculpture with the notion that the transi tomb acts as a complete stylistic antithesis to the norm, the author suggests it may have been a direct result of the Black Death, the Late Medieval Crisis, and the Roman Catholic Church. In studying the transi tomb of Guillaume de Harcigny, a French physician who was made famous by operating on the skull of King Charles VI, this piece aims to address the question: If this is a sculpture of a dead body, can it still be considered a portrait? Studying death during the Middle Ages the critical linchpin in understanding transi tomb sculpture in relation to portraiture. The dead (and the harsh reality of death) were interwoven into the fabric of social life, representing a slightly distant group of people. Guillaume de Harcigny’s transi tomb, therefore, encapsulates the unique personality of Harcigny while simultaneously representing an entire social class altogether. That is why, the ultimate answer to the question is yes, Harcigny’s tomb is a portrait.

The Power of Museum Contexts to Shape Change:

The 20th and 21st centuries have seen an increase in activist art practice. Activist art is not only created in defiance of social and political norms and policies, but also demands positive institutional changes through increased awareness brought about by artistic forms. In the current post-occupy condition, activist art has proliferated in the streets, but also in the museum sphere as well. Historical and contemporary activist art has increasingly been collected and displayed by museums for both their aesthetic and idealistic qualities. This raises questions in both activist and museum communities of whether activist art belongs in a museum, and if its message is diametrically changed in this new context. This essay considers these questions through three case studies of activist art exhibited in American art museums in the past twenty years: The Interventionists: Art in the Social Sphere at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (2004), Agitprop! at the Brooklyn Museum of Art (2015), and An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection, 1940–2017 at the Whitney Museum of American Art (2017). These three case studies reveal how new interpretations, juxtapositions, and relationships of and between activist art objects lead to new ways of analyzing the museum’s role as a public institution. Each exhibition encourages innovation in the museum sphere; whether through placing artists as curators, commissioning community specific activist works, or internally critiquing the museum. Through these examples it becomes clear that exhibitions of activist art can be a vital resource for museums to utilize new strategies to fulfill their missions in socially engaged ways.

A Tea Set, A Bell, and A Wall:

The Octagon, an architecturally unique Federalist house right across the street from the White House, was home to the Tayloes, one of Virginia’s wealthiest plantation enslaving families. After 1814, the Tayloe’s lived in the Octagon permanently. This paper focuses specifically on the time frame around 1828 after John Tayloe had died, leaving Anne Tayloe widowed in D.C. during tumultuous times. “A Tea Set and A Bell: Spatial Distribution of Power and Control at the Octagon” explores the way that three objects, a tea set, wall-mounted bells, and the outer wall of the Octagon House in Washington, D.C., can help weave a narrative about white womanhood, enslavement, and power. The narrative centers on the matron of the house, Anne Tayloe, and the ways that the material qualities of these objects expose stratification and reliance. The objects are interpreted in order to illustrate the way that the very notion of white womanhood relied upon the labor of enslaved people and, specifically, enslaved Black women. The paper uses the study of objects, the Octagon’s archive, and theories such as the Cult of White Womanhood as evidence for these dynamics. The paper touches on the themes of leisure, safety and labor, and the ways that they are each distributed along stratified societal and racial lines.

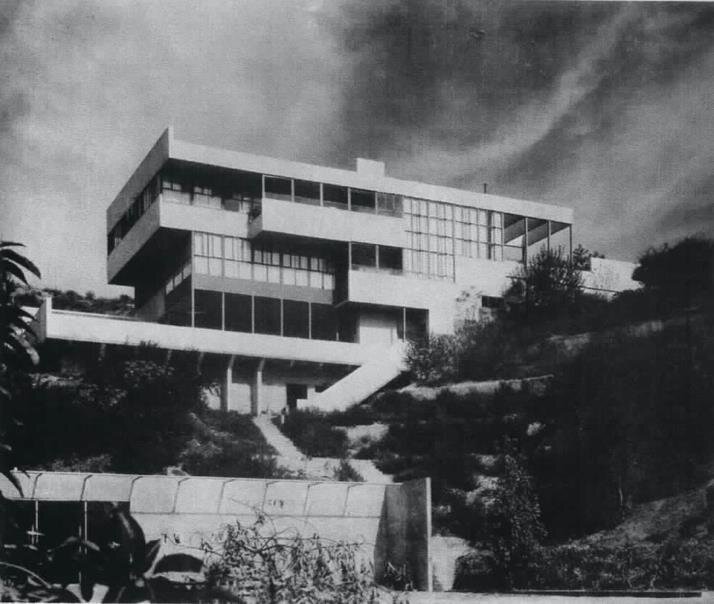

Machines in the Garden:

Richard Neutra’s designs for private houses in the 1930s simultaneously emerge from the Machine Age and resist it. In the 1930s, the United States was in the middle of the time period categorized as the Machine Age, roughly the period between the two world wars. America in the 1930s was in the throes of a love affair with technology, machines, and the products they shaped. This paper examines the ways in which Neutra identified his private houses as “machines,” specifically as “machines in the garden.” It is this distinction and association with nature that separates Neutra from many of his peers categorized in this international movement of the machine aesthetic. Examining his work and the epoque in which they were designed, this paper considers Neutra’s decision to adopt a language of the machine over a more humanistic description of the residences he created. Did Neutra’s language acknowledge the contemporary shift towards a more machine-driven material culture, or did he see his homes as true machines, themselves?

Cultural Consumption, Colonialism, and Nationalism in an Egyptian Alabaster Scarab Beetle

Within a scarab beetle that was acquired during my travels in Egypt, one can read evidence of Egyptian history, both the European imperialist efforts as well as the Egyptian nationalist past, each often expressed through cultural consumption that continues even into today. Ultimately, my scarab beetle is a souvenir from my own travels in Egypt and thus is also taking part in this cultural consumption like so many other souvenirs. I argue that while my scarab beetle is representative of Egyptian culture, it is also part of this broader history of colonial consumption which then triggered the subsequent Egyptian response of manufacturing souvenirs for this demand. Eventually, modern Egyptians also came to foster nationalist sentiments and contest colonial rule, which then encouraged further consumption of Egyptian material culture, although from a place of nationalist pride. These nuances will be further examined throughout this paper, through the use of contemporary literature such as British news articles and short stories, as well as the Egyptian nationalist responses.

The KitchenAid:

First invented in 1908 for professional bakers, the KitchenAid was already being marketed to women for their homes by 1919, and within a few years had become a staple of prosperous suburban homes. The KitchenAid holds a surprising amount of meaning in the American mind. Over the years the KitchenAid has become a cultural symbol of prosperity, progression, idyllic suburbia, female duty, and family values. The history of the KitchenAid connects closely with a major shift that was occurring in America at the turn of the 20th century. Domestic servants were falling out of favor and suddenly affluent women were responsible for the domestic tasks in their homes. Tools like the KitchenAid made this possible, but also increased standards, and created a middle class ideal of home economics, an idea of a wife who is expert in her home duties. Kitchen appliances became a symbol of the American future, a new woman, and a new home. Paradoxically evoking ideas of both modernization and traditional domesticity, the KitchenAid maintains its multiplicity of meanings through its design. An unchanging aesthetic which balances beauty, functionality, and durability, has made the KitchenAid iconic, and has endowed it with a sentimentality that traverses generations, a sentimentality for the future its past users imagined.

Kid Gloves:

The body of the early-modern ruler would never truly be his own. Instead, it served as the physical embodiment of the broader nation state. For the Hapsburgs in the sixteenth century, armor was one key method for uniting the physical body of the king with the military prowess of the nation. This process began at a young age: in the case of Philip III, at the age of seven, when he received a suit of armor produced by Milanese armorer Lucio Piccinino. This paper unites a visual study of gauntlets made for Philip III with studies of the contemporary portraits of Philip III by artists at the Hapsburg courts and historical analysis of Phillip’s education. By analyzing each of these sources, it becomes clear that Phillip’s prince hood was caught in a crossroads between the ancient and the modern. He at once embodied the classical heritage of Greece and Rome, indicated by the decorative program of the armor, and the future of the country, suggested by the armor’s contemporary form and function.