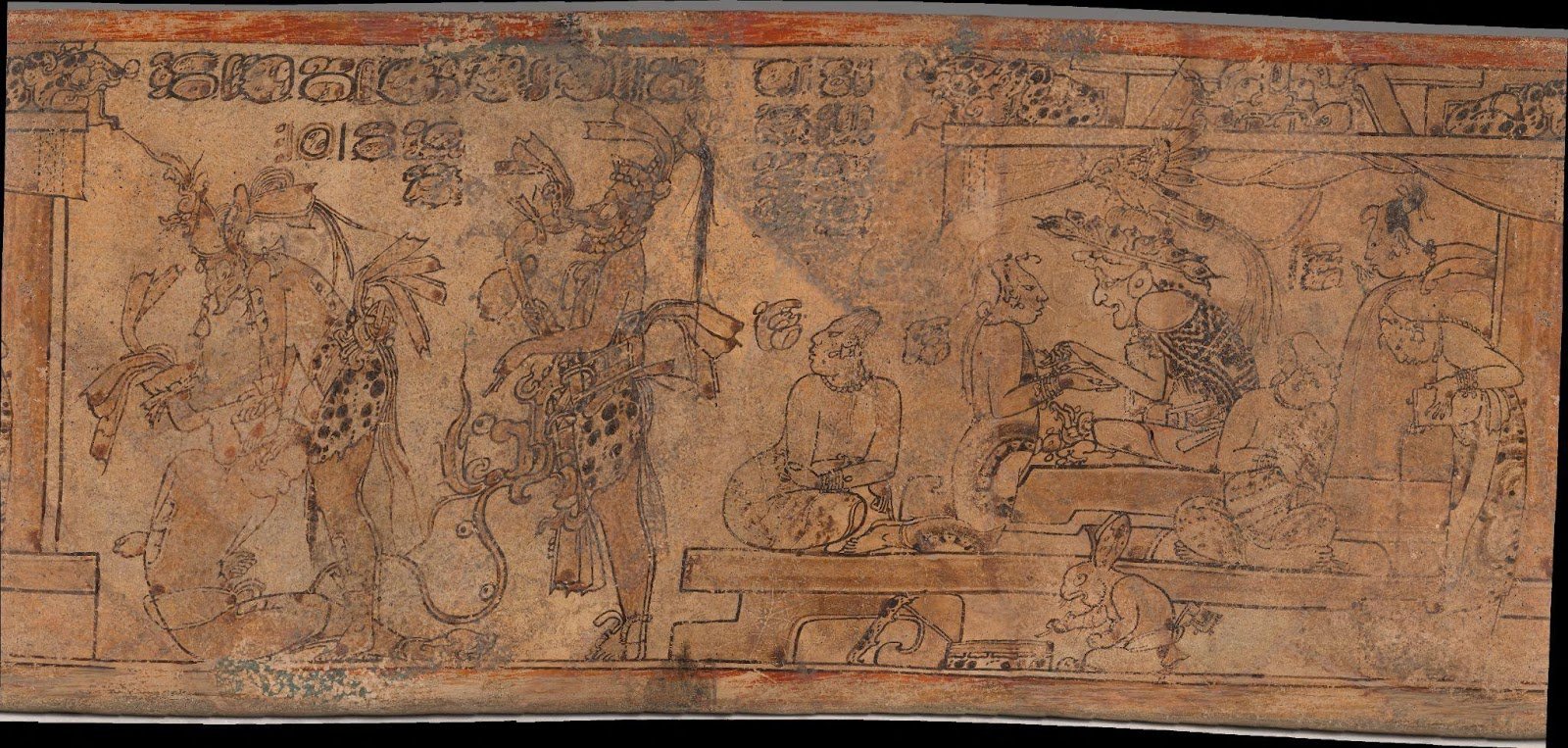

A Closer Look: Funerary Studies, Material Culture, and the Maya

The following analysis investigates literature from the field regarding a carbonate stone bowl, designated as “Bowl with Anthropomorphic Cacao Trees,” found in a tomb and located today in the collection of Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C. The three-roundel bowl is regarded to feature a personified Chocolate God as its central figure. On the other hand, some scholars in the field, including Simon Martin and Karl Taube, posit that the figure considered the “Chocolate God” on this funerary bowl is instead intended to represent the Maize God embodying the Chocolate God in a call for generational rebirth. The following seeks to offer an object biography under the lens of funerary studies and the material culture of the Maya. Visual analysis and study of Maya religious principles are also employed.

A Marxist Approach to Ptolemaic Society: Through the Lens of the Maritime Industry

Ptolemaic Egypt has been studied by classical and archaeological perspectives but has limited its scope to Greco-Roman authors and material analysis which neglects the people. This article applies a Marxist approach created by the author to the archaeological material within the port city of Thonis-Heracleion. This review of the literary landscape of Ptolemaic Egypt suggests a Marxist approach to the archaeological material can show the underrepresented people within the maritime industry and display social groups, inequality, class relations, and modes of production. The material evidence of ships, anchors, weights, nails, faunal remains, and tools that yield evidence of the social dynamics of Thonis-Heracleion. Due to the pandemic, all of the materials are extracted from literary or online resources regarding each site. This approach was found to be stringent but worked, to an extent, within the evidence gathered. Despite, understanding the history, aspects, and application of the manufactured Marxist approach, the archaeological material can expand interpretive opportunities for future study in Ptolemaic Egypt.

“Take me Back to the Good Old Days”: Racism, Berlin Wool Work, and Comfort

Whether they be hung, worn, or used in a multitude of ways, textiles are a tangible component of material culture. They can tell us anything from political culture to stories of nostalgia.This 1876 Berlin wool table cover found in the collection of Winterthur Museum (2020.004) is a curious example of how embroidery and nostalgia intersect. This piece of textile, while overtly racist in its presentations, actually helps us consider the idea of racism in textiles as a teaching object. Even though the imagery of this piece is highly racialized and offensive, it was also evidently loved and cared for by its owners—enough so that the owner, or owners, came back multiple times to make alterations and preserve the piece. This paper discusses not only the tangible aspects of the table cover such as the stitches and design influences, but also the intangible such as what the designs in the cloth tell an audience. Given that many of the designs on this tablecloth were taken from children’s stories, the piece argues that this was intentional in order to “other” Black bodies and garner a certain type of racism—nostalgic racism. This racism is presented in this object via the space of the parlor. The parlor was no longer just a place to be with family and on special occasions, but quickly became one of the most radical forms of conspicuous consumption of the nineteenth century. It was a space to make a statement about how your family perceives the world and vice versa. While this piece might stoke immediate negative feelings, it is critical to remember that those were not the feelings experienced by the owner of this piece and their family. They saw these racist images as amusing and a cultivator for conversation and community.

Close Encounters:

When the COVID-19 pandemic forced museums to close, institutions scrambled to reposition themselves in a virtual climate. Creating virtual programming to reach visitors and patrons in their homes became a priority, and many turned to Google Arts & Culture due to its technical capabilities, visually appealing interface, and brand-name recognition. The Rijksmuseum seized this opportunity, currently using their Google Arts & Culture page to host online exhibits, images of their collections, and virtual ‘tours’ of the space using high-definition panoramic photography. One online exhibit offered by the Rijksmuseum, titled The Milkmaid, is the focus of this review. Though only one of many online exhibits offered by the Rijksmuseum, the theoretical implications the exhibit generates echo the pandemic-induced reimagination and repositioning of museums at large. The brevity inherent in online cultural programming prevents this exhibit from realizing its full educational potential, but The Milkmaid’s technical execution and virtual accessibility is commendable and speaks to broader discussions in the museum studies field. By placing conventional theoretical wisdom in conversation with the uniqueness of our present moment, The Milkmaid reveals itself to be a small but powerful embodiment of the tensions between authenticity and reproduction, physical and virtual, and ability and restriction.

Museum Orientalism:

Although museums that display from all over the world are commonplace in both Europe and North America, their histories are much more complicated than meets the average visitor’s eye. In fact, these “universal survey museums,” like the Louvre, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, are based upon Roman traditions of displaying war trophies. As such, the original purpose of such museums was to attest to the greatness of the modern nation-state, and consequently construe the history of art as the history of the highest European civilizations. Thus, these museum’s histories of collecting and exhibiting the arts of, for example, Asia or Africa requires critical consideration. Inspired greatly by Saidian Orientalism, this article describes and interprets how “East versus West” thinking and scholarship incorporated two early US American museums, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The East-West division influenced how both of these museums came to organize their administrations between experts on art history and experts on “the Orient.” Furthermore, Orientalized juxtapositions, a feature of Hegelian art historical theory popular at the time, formulated how museums organized their exhibition spaces. By following the museum’s gallery program, visitors enacted the evolution of civilization from Orient to Occident, and envisioned the differences between Western and Eastern arts as high and low respectively. This article primarily considers two juxtapositions: Greco-Roman traditions versus Egyptian traditions, and European paintings versus Oriental (East Asian) decorative arts. Part two of this article continues with the history of Orientalism at the MFA and the MET in the 1890s and 1900s. During this time, the both museums solidified the East-West binary as a part of their administrational structure and exhibition layout. Furthermore, museum engagements with East Asia led to the development of another Orientalized binary: East Asian crafts versus Western paintings.

Museum Orientalism:

Recent social justice and decolonial movements have led museums in Europe and North America to address the role they have historically played in maintaining imperial and white-supremacist hegemonies. Although museum scholarship has produced some important work on the history of museums as imperial, racist institutions, few scholars, if any, have attempted to understand the specific ways that Orientalism informed the early formations of the modern, encyclopedic museum of the West. Inspired greatly by Saidian Orientalism, this article describes and interprets how “East versus West” thinking and scholarship incorporated two early US American museums, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The East-West division influenced how both museums came to organize their administrations between experts on art history and experts on “the Orient.” Furthermore, Orientalized juxtapositions, a feature of Hegelian art historical theory popular at the time, formulated how museums organized their exhibition spaces. By following the museum’s gallery program, visitors enacted the evolution of civilization from Orient to Occident and envisioned the differences between Western and Eastern arts as high and low respectively. This article primarily considers two juxtapositions: Greco-Roman traditions versus Egyptian traditions, and European paintings versus Oriental (East Asian) decorative arts. Part one of this article argues that the representational nature of both Orientalism and universal survey museums warrants critical consideration of “East versus West” thinking in such museums and reviews the first two decades of these two museums’ histories regarding Orientalism as thought and a discipline, focusing on their endeavors with the ancient Middle East and Egypt.

Corrigendum to “Her Perfection Is My Wound: A Look at Hans Bellmer’s La Demie Poupée.”

In the article by Wahlen, Samantha, a few claims and terms are in need of further contextualization and qualification. This corrigendum, written with the help of the author and CMSMC editors, seeks to clarify language that may be outdated, and therefore interpreted as harmful or offensive.

Monstrous Women:

Horror, like fashion, appears to be an underestimated tool for understanding political and social change. Both subjects are habitually tossed aside as frivolous and senseless, yet, this article argues that both devices are approachable and digestible in a way that makes them significant. Women are often marginalized in film, a reflection of a larger social issue that manifests clearly in horror films where they are treated violently and exploitatively. This article investigates the costuming of women in a selection of horror films from the 21st century and how these costumes express and intensify the narrative by looking at the tropes of female monsters, specifically the maneater. This trope is associated with sexuality, whether through the overt use of seduction or sexual organs used as weapons. How do costumes in these films work with or against the current narrative of women in society? Exploring the film industry in this context is essential given the industry’s tendency to showcase public opinion in subtle or not so subtle ways. Ideas of the grotesque and its unquestionable connection to the female sex directly relate to these politics and social ideas, but also to horror storytelling and the mythology of monsters we observe throughout time.

Her Perfection is My Wound:

In this art critical essay, Hans Bellmer’s sculpture La Demie Poupée (1971) is proposed as the consummate feminine alter ego of the artist. This thesis is supported by research of the artist’s own writings, drawings, photographs, as well as accounts of friends and the work of notable Bellmer scholars. Through the examination of Bellmer’s personal history, accounts of transvestitism, obsessions with androgyny and the pubescent female, this proposition delves into a brief look at this Surrealist German artist who was and continues to be a shadowy, controversial figure in early twentieth century art history. The importance of this thesis resides in the psychology of Bellmer and is meant to shed light upon the possible extent to which Bellmer created his doll series, why he did so, and what liberation he may have found within his work. Ultimately, the vulnerability and discombobulation of La Demie Poupée attests convincingly of Bellmer’s tormented psyche as well as to the emotional manifestations of his frustration, angst, and need for domination.

Manufacturing Heritage:

Engaging the lenses of art history and cultural heritage studies, this article evaluates the history and functions of the Palazzo Strozzi, a Florentine Renaissance palace re-purposed into an exhibition space and research institution in the twentieth century. This paper addresses the pivotal role of the Fascist regime in the transformation of the building. This article considers the Strozzi’s history, as well as the gaps in the history presented by the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi’s website, and aims to create a more complete, complex picture of its role throughout the twentieth century. Ultimately, this paper suggests that aspects of the Palazzo’s history have been purposefully omitted, due to their irreconcilable political nature.

Culture, Community, and the WeChat Platform in a Time of Crisis

Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, museums have been considered crucial institutions for the preservation and transmission of Chinese culture, civilization, and history. As social and political environments change, the ways that museums support their audiences also transform. Recently, as museums in China reopen after months of closure due to the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, museum directors find themselves deluged with too much information and too many concerns about the post-Covid world to make informed decisions about how use online platforms. This article offers suggestions about how Chinese museums can use WeChat, the most popular social media platform in China, during and after Covid-19. It focuses on how WeChat offers opportunities for museums to foster equal participation in the museum, develop engaging programs, and make collection resources more accessible. The hope is to reimagine Chinese museums to meet the needs of audiences in the post-Covid world.

An Honest Day’s Work:

This paper serves as an exploration of the reliance of open world fantasy role-playing games on evoking emotions of pastoral romanticism in the player. Such games tend to be dominated by rural landscapes, and farming locations and objects often play a central role in the player’s interaction with the world. In particular, the paper will investigate mechanics where the player receives a personal stake in a pastoral setting, such as when a player-controlled hero spends significant game time engaging in farmhouse construction, food production, or other central aspects of rural life. It is in this aspect, the paper argues, that pastoral romanticism creates a significant player appeal entirely separate from the allure of heroic adventuring. Players of fantasy games take on the trappings of the aristocrats of ages past in their idealized engagement with otherwise taxing rural life, and similar to the early modern bourgeoisie, fantasize about escaping from the pressures of a modern industrialist lifestyle just as much as they fantasize about killing dragons. In absence of meaningful control over physical productivity in the real world, this progression towards a “perfect” rural landscape that one creates through shaping the land according to one’s wishes, is an appealing simulation of an activity not available to the average urban or suburban player. However, it simultaneously renders the same player a pseudo-aristocratic interloper into a fairytale version of working-class realities.

An Honest Day’s Work:

This paper serves as an exploration of the reliance of open world fantasy role-playing games on evoking emotions of pastoral romanticism in the player. Such games tend to be dominated by rural landscapes, and farming locations and objects often play a central role in the player’s interaction with the world. In particular, the paper will investigate mechanics where the player receives a personal stake in a pastoral setting, such as when a player-controlled hero spends significant game time engaging in farmhouse construction, food production, or other central aspects of rural life. It is in this aspect, the paper argues, that pastoral romanticism creates a significant player appeal entirely separate from the allure of heroic adventuring. Players of fantasy games take on the trappings of the aristocrats of ages past in their idealized engagement with otherwise taxing rural life, and similar to the early modern bourgeoisie, fantasize about escaping from the pressures of a modern industrialist lifestyle just as much as they fantasize about killing dragons. In absence of meaningful control over physical productivity in the real world, this progression towards a “perfect” rural landscape that one creates through shaping the land according to one’s wishes, is an appealing simulation of an activity not available to the average urban or suburban player. However, it simultaneously renders the same player a pseudo-aristocratic interloper into a fairytale version of working-class realities.

Enigmatic Lives:

The Early Bronze age in Europe (1900-1500 BCE) is characterized by a dramatically shifting social and economic landscape. Populations expanded, trade networks grew, and the use of bronze exploded. Although the typical life cycle of bronze artifacts was cyclical as they were melted down and recycled, some bronzes were treated differently and were instead deposited in graves, hordes, and on their own. Yet, as Bradley (2013) notes, though the deposition of bronzes has been well studied, understanding them has been limited by restrictive interpretations that fail to include the objects’ biography. Object biographies create a platform for researchers to examine the relationships between people and objects and how they change over time, creating a more holistic view of the culture and the object. This methodology is particularly suited for exploring the famous Trundholm Sun Chariot. Although featured extensively in writings on the Nordic Bronze age, research has typically been limited to the object’s significance in explaining early religion, or exchange networks and has ignored the complex relationships this unique bronze object can reveal. Through this object biography, interpretations of the Trundholm Sun Chariot can move beyond singular foci and explore how relationships around bronze are changed and meanings are created as the Chariot moves from raw material to a ritually ‘extinguished’ object and beyond.

The Dual Life of Northwest Coast First Nations Masks in Western Institutions:

The museum frames our ideas about the livelihoods and person hoods of other people, as they are where the public encounters an other—a person different from who they identify as—often they have never met in their daily lives. Taking anthropologist James Clifford’s essay “On Collecting Art and Culture” as its departure, this paper argues that the traditional Western museum’s exhibition form cannot do justice to the histories and lives of non-Western objects, specifically masks from Northwest Coast Indigenous cultures, because the museum’s historical foundation was established by Enlightenment meta-narratives that counter the belief systems of many non-Western people, which reinforce stereotypes about the cultures the objects represent. The author presents three examples of exhibition forms that counter the Western model lifted from Clifford’s conclusion in 1988, demonstrating three distinct alternatives to forms that embrace Enlightenment principles, further oppressing the families and cultures to whom these items belong. The Nuyumbalees Cultural Center in Cape Mudge presents their sacred collection as alive and purposeful through programming and use of the big-house style building to provide a cultural and familial history of the objects and tradition of the potlatch. The Museum at Campbell River’s Treasures of Siwidi gallery activates a family’s contemporary collection of potlatch masks as keepers of history through an aural performance of the legendary narrative. The U’Mitsa Cultural Center’s virtual tour uses contemporary videos, 3D modeling, and language learning tools to animate the historical collection of masks from a variety of carvers and owners in a contemporary framework speaking to the interests of locals and global researchers. In order to create more inclusive, respectful, generative, and accurate display practices that honor the history of these items, museums must take steps to deconstruct the Enlightenment value systems upon which the Western Museum model was founded within their display practices.

Crafting Cottagecore :

This paper explores the internet aesthetic “cottagecore” – its historical origins and rise in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as its connection to craft. Cottagecore can be understood as the projection of the core fantasy of escape to a cottage in the woods to live as if it were a simpler time. As such, the desire to make things with one’s hands as a form of self-sufficiency-based self-care has become associated with cottagecore modes of production. This research considers this aesthetic act of making and its inherent digital engagement through the historical lens of the pastoral, Rousseau’s eighteenth- century romanticism, and William Morris’ nineteenth-century neo-Medievalism. The prime objective of this study is to investigate how cottagecore fits into this lineage, and to consider the implications of its digitization.

By examining activity, craft, and digital making, this research reckons with the inherent contradictions of cottagecore: its glorification of the rural idyll, the handmade, and a bucolic isolationism, as well as its coexistence with the technical, the distance from the material through the digital, and the interconnectedness of the internet. These contradictions manifest through social media platforms like TikTok, whereby the most popular of these acts are documented, produced, and circulated, and consumed as content, creating a continuous social loop of escapism. With these key concepts at the helm, this paper will emphasize the ever-growing intersection between production of material culture and the digital age.

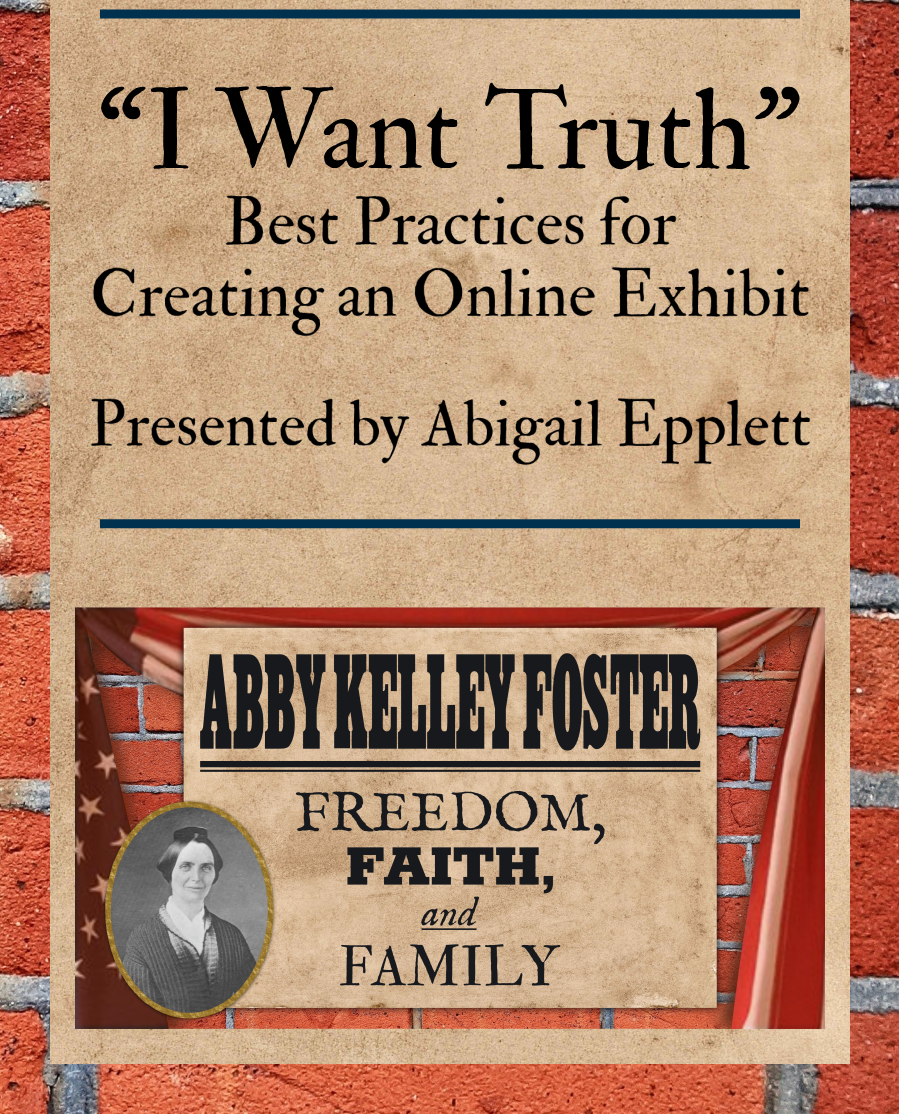

Navigating Copyright Law, Databases, and Accessibility When Creating Online Exhibits

During Summer 2020, I planned, designed, and implemented a born-digital online exhibit called “Abby Kelley Foster: Freedom, Faith, & Family”, which focused on the life of a 19th century human rights activist. While finding materials from the life of Abby Kelley Foster is difficult to begin with — as a devout Quaker who prized living modestly, she left behind few possessions — the closing of museums, libraries, and archives during the pandemic forced me to become even more creative. This paper will focus on the preliminary research, curation of artifacts, and production of a digital exhibit while being limited to materials found only on the web. After turning to digitized archives and collections to find materials, I quickly discovering several novel solutions and brand-new problems. I was impressed by the potential of open access digital archives, but poorly built interfaces and malfunctioning search functions sometimes caused more frustration than fruition. When curating the digital materials, I discovered the limitations of displaying physical objects as part of a standardized, slide-like image. Finally, I wanted this exhibit to be accessible to the widest possible range of visitors. Besides following the accessibility guidelines of the National Park Service, I created supplemental materials with IDEA design principles in mind. Currently, a set of pop-up posters, a narrated video, and a Q&A program cover the same material as the exhibit, with opportunities to expand and diversify the formats in the future. Digital technology was crucial to creating both the basis for this exhibit and future in-person events.

Washington Rallying the Troops at Monmouth (1857):

Since the late-eighteenth century, artists have replicated and disseminated George Washington's image and likeness to preserve his memory and legacy. The popularization of history painting compelled artists to decorate a canvas with decisive moments in the country's founding years. Emanuel Leutze (1816-1868) is one such artist who won praise for his monumental Washington Crossing the Delaware in 1851. Two years later, Leutze created a companion piece, Washington Rallying the Troops at Monmouth (1853). This work shows an unfavorable side of Washington, a commander scrambling to catch his retreating troops. While the public and scholars often focus on Leutze’s more famous image of Washington, the companion piece offers a deviation from sacrosanct portrayals of the first president.

This article examines how David Leavitt commissioned Leutze to recreate this piece in 1857 for his daughter, Elizabeth Leavitt Howe. It argues that the shift in tonality speaks to its change in display, from a monumental canvas intended for a gallery, to the veneration of Washington's image as a form of emulation and active remembrance in a domestic domain. The gifting of the 1857 painting informs the cult of domesticity and code of household governance ever-present in American culture. The painting, therefore, becomes a material way to understand the relationship between objects and family members in nineteenth-century America. Through provenance research, visual analysis, and object networks, this piece will illuminate the divergence in Washington's iconography, while also highlighting the changes made for its placement in a nineteenth-century domestic domain.

The Performativity of Hair in Victorian Mourning Jewellery

Mourning rings were popular items of remembrance in the Victorian era which commonly incorporated the hair of a departed loved one. The role of hair within this type of jewellery is discussed in relation to performativity; a theory that has been successfully employed by a variety of fields to better understand the nature and effects of certain kinds of performance, particularly those that closely relate to the expression and construction of identity. The form of mourning rings, the processes involved in their construction and the messages they communicated to society are examined in reference to performativity, to ascertain the value of considering the mourning ring tradition within this theoretical framework. This article asserts that the processes involved in the construction of mourning rings were not merely representational but performative, as they both symbolise and create transitions between conventional states. Moreover, mourning jewellery was an invented tradition within the larger culture of performative mourning, that addressed the need to reconstruct gendered class identities in the wake of profound social change.

Archaeologist, Adventurer, and Archetype:

In his short life, Archaeologist and British Intelligence Officer John D.S. Pendlebury achieved great acclaim as an archaeologist who studied both ancient Greece and Egypt, becoming director of excavations at both Knossos and Amarna. Called a vigorous romantic, Pendlebury would often immerse himself fully in his work, getting to know each of his sites intimately, which ultimately aided him when he joined British Intelligence. John Pendlebury is your classic hero, a personality that became the archetype for what would later become fictionalized archeologists including but not limited to Indiana Jones, Ramses Emerson, and Julius Kane. Though many may not know his name, they certainly know his profile – an intelligent and ruggedly handsome Englishman who is not afraid to get his hands dirty and ultimately gives up his career in order to save the world from evil forces. On the 80th anniversary of his death, this piece analyses the myth, the man, and the legend of John Pendlebury and shows his influence on fictional depictions of archaeologists even to this day.